[Chico to Harpo]: I need-a money! I'll do anything for money! I'll steal-a for money! I'll kill for money! But hey!...You-a my friend! I kill you for free.

Human understanding depends on stories far more than facts...and stories can be very useful. You'll look first at your own personal narrative, or that story in your head, when you're looking for your keys before you retrace your steps. So the narrative saves a lot of energy.

This is bias that's hard-wired, too. Your brain's visual cortex gets only 10% of its input from data (the optic nerves). The other 90% of inputs are connections to language and memory. You don't even see the world; you see a story you tell yourself about it.

Once we believe a story, it lets us make sense of the world around us, but it also may deceive us by guiding our attention past some inconvenient truths. This kind of (self-)deception is common, throughout human history.

Humans have believed the sun and planets revolve around the earth, for example. The truth is not always welcomed, either. Copernicus wisely decided to publish his theories after he died, but the Pope banned even those posthumous publications, and put Galileo under house arrest for contradicting the official narrative of the time.

The following debunks some common, and still powerful myths about obligation, credit, and money. These myths have been repeated by scholars from Aristotle to Adam Smith and beyond, but myths are not true just because they are repeated. These stories are really plausible explanations that history shows are false. Contradicting the popular narrative is irritating, too. But no irritation, no pearls. Ask an oyster.

Notice that if it appears at all, the state's money--or the temple's--is an afterthought in this story, and the invention of money is independent of any connection to the rest of society, state or religious authorities. This myth also implies that markets do best if they embrace unregulated "free" commerce, minimizing the role of the state--the contention of Neo-liberals, nowadays.

Tracking obligations with precision--credit--appears in Bronze Age Mesopotamia, predating even writing. Writing appeared in roughly 3500 BCE.

Money first appeared as coins in the fifth or sixth century BCE--literally millennia later. Clay tablets specifying obligations, often alehouse bar tabs, tracked what was consumed, and workers paid off debts recorded when the harvest came in.

In such economies, sales were not exchanges of goods for some universal commodity, but an exchange for units of credit. Anthropologist Caroline Humphrey concludes that "No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing".

Even when economies like the one that succeeded the the fall of Rome did not have state-issued money, they calculated the value of exchanges based on previously available money values.

“Money was no more ever ‘invented’ than music or mathematics or jewelry. What we call ‘money’ isn’t a ‘thing’ at all; it’s a way of comparing things mathematically as proportions…” [David Graeber]

Notice that Mesopotamia--the “fertile crescent”--also required labor to maintain the irrigation that made its agriculture so productive, so the presence of the state organizing and maintaining this system was critical. A state like California, so dependent on irrigated crops, appears to understand this.

Slave labor was a component of the maintenance crew, and acquiring slaves was one of the main reasons for wars of conquest, but labor on public works and monuments also provided social cohesion. Archaeology found the work gangs who built the pyramids ate not slave food but feasts as meals. So the pyramids and the floats in the Rose Parade have that much in common.

If nothing else, the myth asserts that money (debt) has nothing but economic value, even if the creditor-friendly statement "Surely one must pay one's debts!" implies implicit morality.

Payment of this kind of early "money" was typically a specific item, usually something of no practical use and could not be substituted by anything else. Some economists limit their definition of money to exclude such impractical tokens, and only apply the term "money" to a socially approved unit of account used to measure debt. There are many kinds of debt and obligations, some we cannot measure with a specific unit of account. Those were the occasion for the first appearance of what became our modern money.

In this context, money had practically magical powers. "The Iroquois believed tribal money (wampum) was so spiritually powerful it could bring back the spirit of dead loved ones. [One Jesuit account describes] the Huron practice of hanging wampum around a captive Native’s neck; if the captive accepted the necklace, he became the living embodiment of a deceased loved one. [from Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value; The False Coin of Our Own Dreams-- David Graeber]

Similarly, sacrifices repay the gods (or bribe them) for favors granted or requested. The bigger the favor, the bigger the sacrifice. The firstborn of the tribal leader or royal family would be the biggest sacrifice...and sacrifice and assassination were rife throughout the royal families of the ancient Middle East.

Note: Part of the point of the story of Isaac and Jacob is that Jehovah does not require the sacrifice of the leader’s first-born. The religious dimension of money also explains those money changers in the Temple whose tables Jesus upset. In fact, a common term for anyone paying to release a debt slave was the "redeemer." This is also a term for messianic figures, demonstrating that obligation to the gods extends all the way from credit to religious feeling.

Another social money, weregild, compensates a family injured by murder. Notice that this type of payment is first socially useful, not a market convenience. It prevents blood feuds that would destroy society otherwise.

In other words, money first appeared not as a market / barter enabler, but as a way to heal societies, and rectify man's position relative to God or the cosmos (i.e. religion). Only later was money the enabler of markets. The ambiguity of whether debt signifies economic or moral/religious obligation persists even today, though, with some problematic results.

In Debt: The First 5,000 Years, David Graeber's treatise on the anthropology of obligation, he begins with the story of a cocktail party encounter with a charitable organization's attorney. Graeber starts telling the attorney how he has been lobbying to forgive third world debt, and the she replies: "Surely one must always repay one's debts!"

The myth embodied in that statement assumes all debts are legitimate, and simple reciprocity requires the borrower to repay any debt undertaken. The power of this myth also lies in the moral/economic ambiguity. To understand the myth, and the condemnation of non-paying debtors, one must also understand that the borrower's obligation goes beyond mere economics, extending into morality.

People who do not pay their debts are bad!

Credit / debt is a way of giving “I owe you one” precision, but exact, standardized units of debt led to many other problems that persist even today. One example from ancient times: pledging one’s spouse, child or even oneself as security for debt was possible. So what happens to debts that are unpayable? Debt slavery? Debtors' prison? Bankruptcy?

The connection of money and debt to ethics and religion is deep, too. The Latin root for “credit” is credere -- to believe. Never mind that the Temple / Palace complex regulated and blessed obligations, credit requires faith. In many ways, ”the value of a unit of currency is not a measure of the value of an object, but the measure of one’s trust [in others]”

Yet history shows that colonizers often saddled their colonies with debts they could not possibly pay as a way of dominating them. Even without a colonial master, crooked rulers could incur the debts, embezzle the money, then leave, leaving the population to deal with the debt repayment. Tom Perkins' Confessions of an Economic Hit Man describes how his economic studies let international underwriting make loans he knew could not possibly be repaid.

Graeber describes some of the consequences: The IMF’s stringent budget restrictions made Madagascar cut back on its mosquito abatement program and roughly ten thousand people died of malaria “to ensure that Citibank wouldn’t have to cut its losses on one irresponsible loan that wasn’t particularly important to its balance sheet anyway.”

The dark side of that statement about the ethical/religious obligation to repay is this: ”...there’s no better way to justify relations founded on violence, to make such relations seem moral, than by reframing them in the language of debt--above all, because it immediately makes it seem that it’s the victim who’s doing something wrong…violent men have been able to tell their victims that those victims owe them something. If nothing else, they ‘owe them their lives’...because they haven’t been killed.”

Interest payable on debt compounds in a geometric progression, growing without limit, while the means of repayment in the real economy are strictly limited by the environment, and/or the available technology. For this reason, Einstein famously called compound interest the most powerful force in the universe.

For an equitable society to exist in which creditors

and debtors can meet at least as quasi-equals, and debt is not an

obligation undertaken at gunpoint, ways of forgiving debts must be built

into the economic system supporting such obligations. Bankruptcy and

"clean slate" jubilees are ways of preventing an economy from producing a

population of debt peons or debt slaves. Such remedies have existed

from the earliest times in Mesopotamia.

Debt Jubilees were common in this time, too. They include debt forgiveness, freeing the debt slaves, and amnesty for exiles.

Law codes formalized the role of money in civil

society. They set amounts of legal interest payable on debts, forbidding usury, and set fines for

wrongdoing, and compensation in money for various infractions.

Preventing debt slavery was particularly important in ancient times since the debt slaves could not serve in the army. To ensure military readiness, ancient rulers would often declare "clean slates," or debt jubilees that wiped out agricultural debt, freed debt slaves, and allowed exiles to return.

On the other hand, colonial powers were reluctant to embrace such jubilees for their colonies. France continued to demand payment from Madagascar, and Haiti. Haiti took from 1804 through 1947 to repay.

The U.S. intervention in post-World-War-II Vietnam also propped up a French-sponsored oligarchy of creditors in that country. The Vietnamese understood that the future only held debt peonage if that structure remained in place, so were very motivated to fight even a far better-armed opponent until victorious.

James Buchanan (1919-2013), a Koch-funded economist and Nobel laureate author of "Public Choice" theory, takes this one step further, asserting that state interference in markets is doomed to failure and corruption ("regulatory capture"), so the private sector is always preferable to state regulation. (For more about Buchanan, see Nancy MacLean's Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America)

Stateless societies did have a kind of money. Such money was really a token to produce social cohesion--like sacrifices to the gods, bridewealth, and weregild--not money for economic purposes or markets. (See Myth 1 [continued] above)

From earliest times, states (or city-states) blessed credit arrangements, legislating to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate obligations. The Code of Hammurabi (1750 BCE) is where we first read about "an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth"--retributive justice. Reciprocity is a kind of morality that amounts to debt repayment. The Code also limited the obligation of commercial borrowers (if thieves stole the goods for which they obtained credit), and the term of debt slavery (the consequence of not paying a loan for which the borrower himself was security).

How could a state create a market? In a basic example, imagine the king wants to employ an army of 10,000. This would be a logistical nightmare to feed, house, train and equip. But if the king pays his army in the official currency ("crowns"), then demands crowns in payment for taxes from the rest of the economy, then he encourages his subjects to make a market that first serves the soldiers, and then serves each other.

This is a simple example, but even in its simplicity, one can see the market created would require regulation, if only to specify what makes a legitimate crown, not a counterfeit.

So the opposition between markets and the state is a myth. Markets do not exist without states to specify what legitimate transactions or means of payment look like. States understand and encourage markets, or markets do not exist.

(See Aeon’s Dark Leviathan for a cautionary tale about the libertarian fantasy of a stateless, law-less market.)

In service to this myth, MBAs learn to measure and compare goods and services, optimizing the productive economy in strictly monetary terms. One of their main tools in this optimization is money-as-measurement. This still includes the quasi-religious belief that pursuing profit excuses any damage done to society, because ultimately, the "invisible hand" of the market will right any wrong done.

An interesting coincidence with this conversation about obligation, money, religion and values: Newton himself wrote more about Christian theology than about physics, and supervised the royal mint.

But Newtonian physics has its shortcomings. Quantum physics addresses those, and in doing so re-introduces uncertainty and probability in its calculations.

So...while markets are very efficient allocators of resources, and physics is a model science, they include inexact measurement. Economics speaks of "externalities"--factors outside the calculation of costs and benefits with conventional accounting. One example: pollution.

Finally, measuring and managing economies strictly by bean counting often overlooks fraud. In deference to the pretense that such crimes do not exist, or are not important, criminal activity still does not appear in the calculation of Gross Domestic Product. In fact, the value of questionable activity like speculation, remains undifferentiated from productive action in that calculation. (See Marianne Mazzucato's The Value of Everything for a discussion of this)

Scams about economics itself are not new, either. In fact an MBA education is founded on the quasi-religious belief that God has an invisible hand, and management can be a "science," like physics, with immutable laws that describe and predict behavior. As it happens, one of the evangelists for this belief--Frederick Winslow Taylor, the man whose thinking encouraged the founders of Wharton Business school to employ him as part of its original faculty--altered his data to fit his preconceptions about time-and-motion studies. Rather than doing real science, and altering his hypotheses to fit the data, by Taylor's own admission, his "adjustments" to data ranged from 20% to 225%!

As much as it can include calculation, management really is a liberal art, not science. [See Matthew Stewart's The Management Myth for more about this.]

If nothing else, one cannot call raising children, caring for the elderly, or building long-lasting infrastructure "profitable" according to most MBA calculations, which typically focus on short-term, money return and profitability.

How influential is this myth? The financial sector now claims 40% of the American economy's profits. Its values pervade decisions from the productive part of the economy, too. It was more profitable to tolerate a Pinto gas tank and pay damages to those injured than to fix it. GM saved 97¢ on an ignition part that killed people.

So yes, money lets us calculate the value of things, and may even stand in as payment for debts that are unpayable, but money is not the only measurement that matters.

In its bold misstatement of reality, this myth conflates such (currency creator, National) 'Debt' with (currency user) household debt.

If you have a bank account, that's your asset...but the bank's liability (debt). When you write a check, you are assigning a portion of the bank's debt to the payee. Currency is checks made out to "cash" in fixed amounts, and appears in our central bank's bookkeeping as a liability.

The common name for all the dollar financial assets out in the economy: National 'Debt.'

Imagine a crowd demanding their bank give them smaller accounts, charge bigger fees, pay lower interest. Why?...because they are worried about the bank’s indebtedness (to its depositors).

Not a very sensible picture, is it? Yet it’s a commonplace for the press and American public to encourage just that.

Significant National ‘Debt’ reductions have occurred seven times since 1776. Such "surpluses" are always followed by a Great Depression-sized hole in the economy. The root of the problem is that National 'Debt' is typically the citizens' savings. Diminishing savings injects fragility into the economy. Debtors can't rely on reserves to pay their debts, so waves of asset forfeitures and foreclosures follow.

The state - a currency creator - is distinct from the individuals / households - currency users.

This is a systemic (not individual) problem, too. Collective action offers the only solution feasible.

Notice that bidding must occur before inflation occurs, too. The state could deposit some trillion-dollar coins and our central bank, but that act alone would not trigger inflation.

At the onset of the Great Recession, in 2007-8, according to its own audit, the Fed extended $16 - $29 trillion in credit to cure the frauds of the financial sector. (For only $9 trillion it could have paid off everyone's mortgage, but apparently it was more important to save the banks.) In this case money was not bidding for goods or services, it was retiring liabilities, so despite the enormous amount of money issued, no surge of inflation occurred.

So...could government offer a job to everyone who is unemployed without raising taxes or causing inflation? Government makes the money by fiat, not by collecting taxes (see Myth #7 below), and no one else is bidding for the unemployed, so no bidding or inflation would occur.

Even the “good old days” when we had gold-backed money, we had less gold than currency--only 25% of dollars actually had gold backing when Nixon “closed the gold window” in 1971.

David Graeber notes that, historically, currency has had gold backing for less than two centuries in the five millennia he covers. Gold backing would also disappear whenever war came along. Lincoln fought the Civil War with greenbacks, for example. FDR eliminated the dollar’s conversion to gold in World War II.

Interesting fact: Historically, Graeber notes that people value money as only its commodity value if it’s distant from its issuing state. The state simply declares its value regardless of the commodity, but that declaration grows less important with distance.

If we need a government program, we must cut government spending elsewhere, or raise taxes.This is Nancy Pelosi's "Pay-Go" policy.

Government is the monopoly provider of (non-counterfeit) dollars. Government cannot be provisioned by taxes. Where would people get dollars with which to pay those taxes if government didn't spend them out into the economy first?

Government first spends, then asks for some money back in taxes. What do we call the dollar financial assets it leaves behind, untaxed? Answer: National 'Debt'!

Governments with sovereign, fiat currency and floating exchange rates are the only fiscally unconstrained players in the economy.

Why get more money to the bulk of the population (one example: eliminate FICA taxes)? Answer: Currently, 40 percent of adults can’t cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing. We continue to have a money shortage. Who profits from this shortage? Creditors.

Human understanding depends on stories far more than facts...and stories can be very useful. You'll look first at your own personal narrative, or that story in your head, when you're looking for your keys before you retrace your steps. So the narrative saves a lot of energy.

This is bias that's hard-wired, too. Your brain's visual cortex gets only 10% of its input from data (the optic nerves). The other 90% of inputs are connections to language and memory. You don't even see the world; you see a story you tell yourself about it.

Once we believe a story, it lets us make sense of the world around us, but it also may deceive us by guiding our attention past some inconvenient truths. This kind of (self-)deception is common, throughout human history.

Humans have believed the sun and planets revolve around the earth, for example. The truth is not always welcomed, either. Copernicus wisely decided to publish his theories after he died, but the Pope banned even those posthumous publications, and put Galileo under house arrest for contradicting the official narrative of the time.

The following debunks some common, and still powerful myths about obligation, credit, and money. These myths have been repeated by scholars from Aristotle to Adam Smith and beyond, but myths are not true just because they are repeated. These stories are really plausible explanations that history shows are false. Contradicting the popular narrative is irritating, too. But no irritation, no pearls. Ask an oyster.

Myth #1: Money was invented to enable barter...

This myth says societies first had barter economies, then invented money, and finally relied on credit to transact their economic business. One version describes how Robinson Crusoe and Friday agreed to settle their accounts in seashells rather than rely on the coincidence of needs in their two-person, barter economy.Notice that if it appears at all, the state's money--or the temple's--is an afterthought in this story, and the invention of money is independent of any connection to the rest of society, state or religious authorities. This myth also implies that markets do best if they embrace unregulated "free" commerce, minimizing the role of the state--the contention of Neo-liberals, nowadays.

The truth...

Tracking obligations with precision--credit--appears in Bronze Age Mesopotamia, predating even writing. Writing appeared in roughly 3500 BCE.

Money first appeared as coins in the fifth or sixth century BCE--literally millennia later. Clay tablets specifying obligations, often alehouse bar tabs, tracked what was consumed, and workers paid off debts recorded when the harvest came in.

| A pay stub from Uruk...Workers were paid in beer! |

Even when economies like the one that succeeded the the fall of Rome did not have state-issued money, they calculated the value of exchanges based on previously available money values.

“Money was no more ever ‘invented’ than music or mathematics or jewelry. What we call ‘money’ isn’t a ‘thing’ at all; it’s a way of comparing things mathematically as proportions…” [David Graeber]

Notice that Mesopotamia--the “fertile crescent”--also required labor to maintain the irrigation that made its agriculture so productive, so the presence of the state organizing and maintaining this system was critical. A state like California, so dependent on irrigated crops, appears to understand this.

| Mesopotamian irrigation, recreated. |

Slave labor was a component of the maintenance crew, and acquiring slaves was one of the main reasons for wars of conquest, but labor on public works and monuments also provided social cohesion. Archaeology found the work gangs who built the pyramids ate not slave food but feasts as meals. So the pyramids and the floats in the Rose Parade have that much in common.

Myth #1 [continued]:...Money is economic, not moral or religious

The myth: No social values and certainly no religion appears in the myth of money as an enabler of barter, just willing buyers and sellers. Robinson Crusoe and Friday agree seashells will stand in as tokens of obligation, and the obligation is strictly an economic matter, nothing to do with morality, reciprocity or religion.If nothing else, the myth asserts that money (debt) has nothing but economic value, even if the creditor-friendly statement "Surely one must pay one's debts!" implies implicit morality.

The truth...

In ordinary usage, tokens (money) as a means of repaying one's debts originated as a moral obligation for reciprocity, not part of some economic transaction. In fact, money originally appeared as a way of repaying "un-payable" debts. Examples include things like: sacrifices to repay the gods for their favors, bridewealth (like dowries), and weregild (social justice payments). All of these are meaningless without social context, and were not denominated in an abstract unit of measurement of debts.Payment of this kind of early "money" was typically a specific item, usually something of no practical use and could not be substituted by anything else. Some economists limit their definition of money to exclude such impractical tokens, and only apply the term "money" to a socially approved unit of account used to measure debt. There are many kinds of debt and obligations, some we cannot measure with a specific unit of account. Those were the occasion for the first appearance of what became our modern money.

|

| King Phillip with a wampum belt |

In this context, money had practically magical powers. "The Iroquois believed tribal money (wampum) was so spiritually powerful it could bring back the spirit of dead loved ones. [One Jesuit account describes] the Huron practice of hanging wampum around a captive Native’s neck; if the captive accepted the necklace, he became the living embodiment of a deceased loved one. [from Toward an Anthropological Theory of Value; The False Coin of Our Own Dreams-- David Graeber]

Similarly, sacrifices repay the gods (or bribe them) for favors granted or requested. The bigger the favor, the bigger the sacrifice. The firstborn of the tribal leader or royal family would be the biggest sacrifice...and sacrifice and assassination were rife throughout the royal families of the ancient Middle East.

Note: Part of the point of the story of Isaac and Jacob is that Jehovah does not require the sacrifice of the leader’s first-born. The religious dimension of money also explains those money changers in the Temple whose tables Jesus upset. In fact, a common term for anyone paying to release a debt slave was the "redeemer." This is also a term for messianic figures, demonstrating that obligation to the gods extends all the way from credit to religious feeling.

Another social money, weregild, compensates a family injured by murder. Notice that this type of payment is first socially useful, not a market convenience. It prevents blood feuds that would destroy society otherwise.

In other words, money first appeared not as a market / barter enabler, but as a way to heal societies, and rectify man's position relative to God or the cosmos (i.e. religion). Only later was money the enabler of markets. The ambiguity of whether debt signifies economic or moral/religious obligation persists even today, though, with some problematic results.

Myth #2: "Surely one must always repay one's debts!"...

In Debt: The First 5,000 Years, David Graeber's treatise on the anthropology of obligation, he begins with the story of a cocktail party encounter with a charitable organization's attorney. Graeber starts telling the attorney how he has been lobbying to forgive third world debt, and the she replies: "Surely one must always repay one's debts!"

The myth embodied in that statement assumes all debts are legitimate, and simple reciprocity requires the borrower to repay any debt undertaken. The power of this myth also lies in the moral/economic ambiguity. To understand the myth, and the condemnation of non-paying debtors, one must also understand that the borrower's obligation goes beyond mere economics, extending into morality.

People who do not pay their debts are bad!

The truth...

The moral obligation to repay overlooks several things. For example: the lender's responsibility to underwrite the loan. Should debts incurred to bet on a hot tip at the race track be considered legitimate? Should the state enforce repayment if the loan was so unrealistic that it really was a pretext for foreclosing on the security? (Something illegal in even pre-1776 American colonies).Credit / debt is a way of giving “I owe you one” precision, but exact, standardized units of debt led to many other problems that persist even today. One example from ancient times: pledging one’s spouse, child or even oneself as security for debt was possible. So what happens to debts that are unpayable? Debt slavery? Debtors' prison? Bankruptcy?

The connection of money and debt to ethics and religion is deep, too. The Latin root for “credit” is credere -- to believe. Never mind that the Temple / Palace complex regulated and blessed obligations, credit requires faith. In many ways, ”the value of a unit of currency is not a measure of the value of an object, but the measure of one’s trust [in others]”

“After all, isn’t paying one’s debt what morality is supposed to be all about? Giving people what is due them. Accepting one’s responsibilities. Fulfilling one’s obligations to others, just as one would expect them to fulfill their obligations to you. What could be a more obvious example of shirking one’s responsibilities than reneging on a promise, or refusing to pay a debt?”

Yet history shows that colonizers often saddled their colonies with debts they could not possibly pay as a way of dominating them. Even without a colonial master, crooked rulers could incur the debts, embezzle the money, then leave, leaving the population to deal with the debt repayment. Tom Perkins' Confessions of an Economic Hit Man describes how his economic studies let international underwriting make loans he knew could not possibly be repaid.

Graeber describes some of the consequences: The IMF’s stringent budget restrictions made Madagascar cut back on its mosquito abatement program and roughly ten thousand people died of malaria “to ensure that Citibank wouldn’t have to cut its losses on one irresponsible loan that wasn’t particularly important to its balance sheet anyway.”

The dark side of that statement about the ethical/religious obligation to repay is this: ”...there’s no better way to justify relations founded on violence, to make such relations seem moral, than by reframing them in the language of debt--above all, because it immediately makes it seem that it’s the victim who’s doing something wrong…violent men have been able to tell their victims that those victims owe them something. If nothing else, they ‘owe them their lives’...because they haven’t been killed.”

Myth #2 [continued]:...although forgiving debts is a nice, optional thing.

The myth: If a debtor is morally reprehensible when s/he does not pay debts owed, then it takes an exceptionally nice person to forgive debts. In this story, religion exists to encourage "nice," but not necessary, behavior.The truth....

Interest payable on debt compounds in a geometric progression, growing without limit, while the means of repayment in the real economy are strictly limited by the environment, and/or the available technology. For this reason, Einstein famously called compound interest the most powerful force in the universe.

| Debt grows infinite while the means of repayment (the real economy) lags |

Debt Jubilees were common in this time, too. They include debt forgiveness, freeing the debt slaves, and amnesty for exiles.

| The Rosetta Stone includes a debt jubilee |

Babylon’s Legacy in the Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Law

About 25% of the population of Judah was deported to Babylon in 600 BCE, so the Babylonian traditions were integrated into the Hebrew Bible (AKA the Old Testament). Other legacies of the Babylonian exile: Prophets (e.g. Ezekiel, Isaiah) Church-going (Synagogues keep the Jewish culture alive with periodic meetings).Preventing debt slavery was particularly important in ancient times since the debt slaves could not serve in the army. To ensure military readiness, ancient rulers would often declare "clean slates," or debt jubilees that wiped out agricultural debt, freed debt slaves, and allowed exiles to return.

Modern Debt Jubilees

Debt jubilees were not just ancient practice. They successfully revived the post-World War II economies of Japan and Germany. Their “miraculous” post-War recoveries included such jubilees, releasing the population from their obligations to the previous, ruling oligarchs.On the other hand, colonial powers were reluctant to embrace such jubilees for their colonies. France continued to demand payment from Madagascar, and Haiti. Haiti took from 1804 through 1947 to repay.

The U.S. intervention in post-World-War-II Vietnam also propped up a French-sponsored oligarchy of creditors in that country. The Vietnamese understood that the future only held debt peonage if that structure remained in place, so were very motivated to fight even a far better-armed opponent until victorious.

Myth #3: Markets appear and thrive without state initiative or interference.

In this myth, Robinson Crusoe and Friday need no governing authority to tell them what is money, or to dictate its value in retiring obligations, or really to tell them what amounted to a legitimate obligation. A state would only interfere with commerce.James Buchanan (1919-2013), a Koch-funded economist and Nobel laureate author of "Public Choice" theory, takes this one step further, asserting that state interference in markets is doomed to failure and corruption ("regulatory capture"), so the private sector is always preferable to state regulation. (For more about Buchanan, see Nancy MacLean's Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right's Stealth Plan for America)

The truth...

Economic money and markets appear only in societies with state institutions. Stateless societies exist, but they don’t have money (as we use it) or markets. So...“States create markets. Markets require states.” [Graeber]Stateless societies did have a kind of money. Such money was really a token to produce social cohesion--like sacrifices to the gods, bridewealth, and weregild--not money for economic purposes or markets. (See Myth 1 [continued] above)

From earliest times, states (or city-states) blessed credit arrangements, legislating to distinguish legitimate from illegitimate obligations. The Code of Hammurabi (1750 BCE) is where we first read about "an eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth"--retributive justice. Reciprocity is a kind of morality that amounts to debt repayment. The Code also limited the obligation of commercial borrowers (if thieves stole the goods for which they obtained credit), and the term of debt slavery (the consequence of not paying a loan for which the borrower himself was security).

How could a state create a market? In a basic example, imagine the king wants to employ an army of 10,000. This would be a logistical nightmare to feed, house, train and equip. But if the king pays his army in the official currency ("crowns"), then demands crowns in payment for taxes from the rest of the economy, then he encourages his subjects to make a market that first serves the soldiers, and then serves each other.

This is a simple example, but even in its simplicity, one can see the market created would require regulation, if only to specify what makes a legitimate crown, not a counterfeit.

So the opposition between markets and the state is a myth. Markets do not exist without states to specify what legitimate transactions or means of payment look like. States understand and encourage markets, or markets do not exist.

(See Aeon’s Dark Leviathan for a cautionary tale about the libertarian fantasy of a stateless, law-less market.)

Myth #4: If it can’t be measured or monetized, it doesn’t exist.

The confusion between economic and moral values lets people make purely monetary calculations stand in for morality, sometimes taking that law "An eye for an eye" too far. Gandhi says "An eye for an eye [without forgiveness] only ends up making the whole world blind."In service to this myth, MBAs learn to measure and compare goods and services, optimizing the productive economy in strictly monetary terms. One of their main tools in this optimization is money-as-measurement. This still includes the quasi-religious belief that pursuing profit excuses any damage done to society, because ultimately, the "invisible hand" of the market will right any wrong done.

The truth...

The yearning for certainty is an all-too-human tendency. I'd suggest social scientists envy Newton's physics, the purest of cause-and-effect machines, as the standard for their discipline. And Newton's physics solved some very large problems, too--everything from the shape of the cosmos to the trajectory of artillery shells. In tribute, Alexander Pope wrote: "Nature and nature's laws lay hid in the night. God said, Let Newton be! and all was light!"An interesting coincidence with this conversation about obligation, money, religion and values: Newton himself wrote more about Christian theology than about physics, and supervised the royal mint.

But Newtonian physics has its shortcomings. Quantum physics addresses those, and in doing so re-introduces uncertainty and probability in its calculations.

So...while markets are very efficient allocators of resources, and physics is a model science, they include inexact measurement. Economics speaks of "externalities"--factors outside the calculation of costs and benefits with conventional accounting. One example: pollution.

Finally, measuring and managing economies strictly by bean counting often overlooks fraud. In deference to the pretense that such crimes do not exist, or are not important, criminal activity still does not appear in the calculation of Gross Domestic Product. In fact, the value of questionable activity like speculation, remains undifferentiated from productive action in that calculation. (See Marianne Mazzucato's The Value of Everything for a discussion of this)

Scams about economics itself are not new, either. In fact an MBA education is founded on the quasi-religious belief that God has an invisible hand, and management can be a "science," like physics, with immutable laws that describe and predict behavior. As it happens, one of the evangelists for this belief--Frederick Winslow Taylor, the man whose thinking encouraged the founders of Wharton Business school to employ him as part of its original faculty--altered his data to fit his preconceptions about time-and-motion studies. Rather than doing real science, and altering his hypotheses to fit the data, by Taylor's own admission, his "adjustments" to data ranged from 20% to 225%!

As much as it can include calculation, management really is a liberal art, not science. [See Matthew Stewart's The Management Myth for more about this.]

If nothing else, one cannot call raising children, caring for the elderly, or building long-lasting infrastructure "profitable" according to most MBA calculations, which typically focus on short-term, money return and profitability.

How influential is this myth? The financial sector now claims 40% of the American economy's profits. Its values pervade decisions from the productive part of the economy, too. It was more profitable to tolerate a Pinto gas tank and pay damages to those injured than to fix it. GM saved 97¢ on an ignition part that killed people.

So yes, money lets us calculate the value of things, and may even stand in as payment for debts that are unpayable, but money is not the only measurement that matters.

Myth #5: Government “Debt” is harmful, even for future generations (“Debt” impairs savings!)

The myth: America's National Debt looms over its economy like the sword of Damocles, casting a shadow of unpayable debt across the current economy and generations to come.| Mainstream media promotes the myth, too. |

The truth....

Government 'Debt' is nothing like household debt. It's more like bank debt.If you have a bank account, that's your asset...but the bank's liability (debt). When you write a check, you are assigning a portion of the bank's debt to the payee. Currency is checks made out to "cash" in fixed amounts, and appears in our central bank's bookkeeping as a liability.

| A "note" is a legal term for an IOU (see "Federal Reserve Note" on your dollars) |

| Notice how government liability mirrors private sector (and foreign trade / capital account) asset |

The common name for all the dollar financial assets out in the economy: National 'Debt.'

Imagine a crowd demanding their bank give them smaller accounts, charge bigger fees, pay lower interest. Why?...because they are worried about the bank’s indebtedness (to its depositors).

Not a very sensible picture, is it? Yet it’s a commonplace for the press and American public to encourage just that.

Significant National ‘Debt’ reductions have occurred seven times since 1776. Such "surpluses" are always followed by a Great Depression-sized hole in the economy. The root of the problem is that National 'Debt' is typically the citizens' savings. Diminishing savings injects fragility into the economy. Debtors can't rely on reserves to pay their debts, so waves of asset forfeitures and foreclosures follow.

The state - a currency creator - is distinct from the individuals / households - currency users.

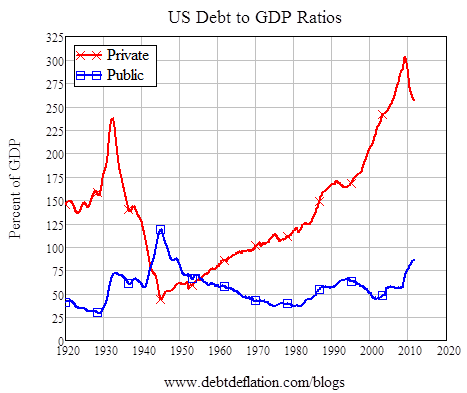

|

| Private debt peaks in 1929 and at the beginning of the Great Recession, just before massive downturns |

Myth #6: Printing money causes inflation.

The myth: Inflation inevitably has its source in central banks issuing too much money. We must restrict even issuers of the technically unlimited fiat money, otherwise all that money will cause [hyper-]inflation, debasing the currency.The truth...

In theory, a sovereign, fiat currency issuer could issue unlimited money, and outbid the private sector for (limited) goods and services in the real economy, making prices rise. But a Cato Institute study of 56 hyperinflations throughout human history discloses that none were caused by central banks run amok. Shortages of goods, and balance of payments problems preceded any excessive money printing or hyperinflation.Notice that bidding must occur before inflation occurs, too. The state could deposit some trillion-dollar coins and our central bank, but that act alone would not trigger inflation.

At the onset of the Great Recession, in 2007-8, according to its own audit, the Fed extended $16 - $29 trillion in credit to cure the frauds of the financial sector. (For only $9 trillion it could have paid off everyone's mortgage, but apparently it was more important to save the banks.) In this case money was not bidding for goods or services, it was retiring liabilities, so despite the enormous amount of money issued, no surge of inflation occurred.

Saying more money causes inflation is roughly like saying printing more inches on tape measures make things longer.

About national bankruptcy:

Since money is a measurement, not a commodity, sovereign, fiat money creators with a floating exchange rate, and debts payable in the money they create can never actually run out of money. That means the U.S. government can never be "bankrupt" (involuntarily insolvent). Greece is not a monetary sovereign; it can't make drachmas any more, and must rely on externally-produced euros. That situation is the origin of lots of Eurozone problems.So...could government offer a job to everyone who is unemployed without raising taxes or causing inflation? Government makes the money by fiat, not by collecting taxes (see Myth #7 below), and no one else is bidding for the unemployed, so no bidding or inflation would occur.

Even the “good old days” when we had gold-backed money, we had less gold than currency--only 25% of dollars actually had gold backing when Nixon “closed the gold window” in 1971.

David Graeber notes that, historically, currency has had gold backing for less than two centuries in the five millennia he covers. Gold backing would also disappear whenever war came along. Lincoln fought the Civil War with greenbacks, for example. FDR eliminated the dollar’s conversion to gold in World War II.

Interesting fact: Historically, Graeber notes that people value money as only its commodity value if it’s distant from its issuing state. The state simply declares its value regardless of the commodity, but that declaration grows less important with distance.

Myth #7: Taxes fund government programs. (and Social Security is in peril!)

The headlines regularly remind us: We're out of money! We're insolvent! We cannot possibly pay off that national 'debt' because we can't issue more currency (see myth #6)!If we need a government program, we must cut government spending elsewhere, or raise taxes.This is Nancy Pelosi's "Pay-Go" policy.

The truth....

Government is the monopoly provider of (non-counterfeit) dollars. Government cannot be provisioned by taxes. Where would people get dollars with which to pay those taxes if government didn't spend them out into the economy first?

Government first spends, then asks for some money back in taxes. What do we call the dollar financial assets it leaves behind, untaxed? Answer: National 'Debt'!

Governments with sovereign, fiat currency and floating exchange rates are the only fiscally unconstrained players in the economy.

Why get more money to the bulk of the population (one example: eliminate FICA taxes)? Answer: Currently, 40 percent of adults can’t cover a $400 emergency expense without borrowing. We continue to have a money shortage. Who profits from this shortage? Creditors.

Conclusions

This account began with a reminder of how important narratives are to human understanding. If nothing else, you now have some alternatives to the conventional narratives. What are the alternatives?

1. Credit / Money is a social construct. Rather than enable barter, it first served to prevent feuds over unpayable debts, or repaid gods for their favor. Credit preceded money, not barter.

2. Lenders have a responsibility to make loans that can be repaid, just as much as debtors have a responsibility to pay them. The mathematics of interest compounding means that debts can become

unpayable, too. Clean slates, jubilees, or at least bankruptcy must exist or

borrowers become debt peons, effectively slaves of lenders.

3. Markets are possible thanks to state encouragement and regulation. They do not exist without a state to sponsor and maintain them.

4. Money measures and compares things, but some things are unmeasurable. Relying strictly on accounting to always produce good outcomes is unrealistic.

5. Government 'Debt' is like bank debt, not household debt. Bank debts are depositors' asset. National 'Debt' is the common term for the dollar financial assets out in the private economy.

6. Shortages of goods and balance of payment problems initiate inflationary periods--like the oil shortages in the '70s. Shortage, not money printing, is the critical element in inflation.

7. Taxes make money valuable, they don't (and can't) provision governments that make the money.

Spending money is how society allocates resources. This alternative narrative leads to at least the possibility of a dramatic change, opening up a whole world of possibilities. Excuses or anxiety-provoking warnings citing money shortages are not valid in most modern economies. Government does not have to raise taxes to provision new programs. Society can realistically tackle systemic problems ranging from unemployment to global warming.

Now...what will you do with this knowledge?

....The above is based on the work of Michael Hudson, David Graeber, and the Modern Money Theorists (among them Warren Mosler, Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, Steve Keen and Bill Mitchell). Thanks to Randall Wray and Warren Mosler for reviewing and correcting the above.

....The above is based on the work of Michael Hudson, David Graeber, and the Modern Money Theorists (among them Warren Mosler, Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, Steve Keen and Bill Mitchell). Thanks to Randall Wray and Warren Mosler for reviewing and correcting the above.

By this theory the federal government can continue creating money and doling out through bonds in fiat currencies. But, as I see it, the consumer who keeps borrowing on credit, but will reach a limit to paying it back which forces him to reduce his new purchases, thereby driving down demand for goods. Or under our current administration, the consumer will be paying the added tariffs thereby pricing him out of his demand for goods.

ReplyDeleteYou are correct. The fundamental difference between government and consumers is that, in this case, the government is fiscally unconstrained. It *makes* the money!

ReplyDeleteFor just one example, the government commandeered 50% of the economy for World War II. (Only 5% would be necessary for the Green New Deal)

There is a (theoretical) limitation in how much government can buy--after all, the real, non-financial economy is not limitless. Trying to buy what's not there could be inflationary...but central banks never historically "printed" too much money to kick off inflation. Shortages of goods have done that...and inflation is the last of our worries now.

Very thankful for this post too. I've been in groups trying to explain MMT and generally end up floundering in what feels like a graduate level class when I need like kindergarten level!

ReplyDelete