The most shocking insights to come out of the Strong Towns movement are that the best financial investments cities can make are small and almost always in our poorest neighborhoods.

To be clear: By “best” I’m not talking about investments that are the most equitable or somehow judged to be morally superior. And I’m also not using the word “investment” to indicate some abstract notion of future payoffs, like the suggestion that investing in better healthcare or workforce development will theoretically pay off someday according to some economist’s PhD thesis.

What I’m talking about is hard currency. Invest a dollar and get back a dollar plus a real return on that investment. This is shrewd economics, the kind that genuinely builds wealth over time.

Here’s one more shocking detail: Not only are small investments in poor neighborhoods the lowest risk, highest returning way for a community to build wealth, they are also the best way to lift people out of poverty without displacing them from their neighborhood. That is the core of the Strong Towns approach to capital investment.

Mapping the Finance of Poverty

I assisted the data analytics firm Urban3 with preparing a profit and loss map for the city of Lafayette, Louisiana. We examined and mapped all of the ongoing expenses the community experienced, including maintenance of roads and streets, sidewalks and drainage systems, underground pipes, transit service, public safety and more.

We also analyzed and mapped all of the city’s sources of revenue, including sales and property tax income as well as utility fees and other ongoing revenue streams.

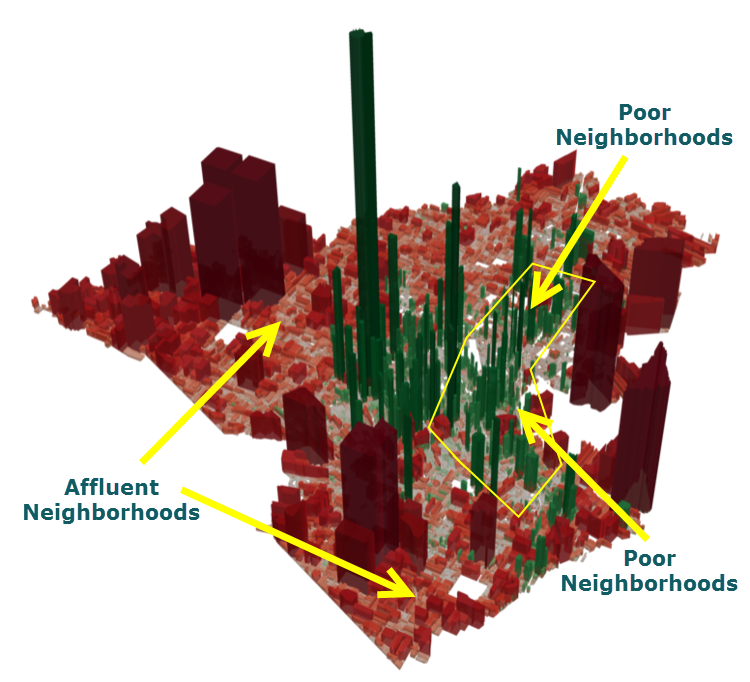

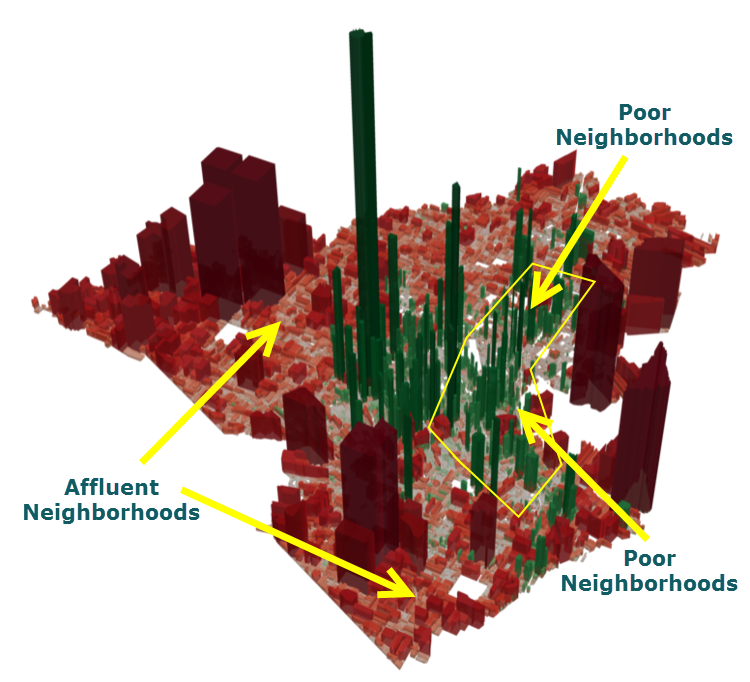

When we finished this analysis, we mashed all of these maps together to provide a profit and loss map for the entire city. The map indicates in dark green the profitable parcels, those that contribute more in taxes and fees than they require in ongoing service and maintenance costs. The map also shows in red the parcels where the community is losing money, places that require more annually to serve and maintain than they contribute in taxes and fees.

The higher the bar, the greater the disparity. Here is Lafayette’s profit and loss map.

This map, created by Urban3, illustrates the tax value of each property in Lafayette. Green areas create a net profit and red areas are a net loss. The higher the block goes, the larger the amount of profit/loss. A blue/green version now available thanks to the work of a generous contributor (for those that are red/green colorblind).

There are two distinct areas that are profitable. The first is the core of the city, the historic downtown located in the center of the map. The second is a crescent of green that lies just to the east of the downtown. This includes the poorest neighborhoods in the community, areas that are in extreme distress.

Here are photos of these neighborhoods. The core downtown is improving but still struggles in many ways. It doesn’t pass the eye test for prosperity. The poor neighborhoods are worse and would be considered blighted by any standard.

The rest of the map is red. The areas where the city is losing money includes all the big box stores, strip malls, franchise restaurants, gas stations, and windy residential streets with the large lots and cul-de-sacs. These are the affluent parts of Lafayette.

Here are some representative photos of these areas, which should be familiar to everyone as it is the ubiquitous pattern of development adopted here in the United States after World War II.

What becomes obvious with this map is that the poor neighborhoods are profitable while the affluent neighborhoods are not. Throughout the poor neighborhoods, the city is already bringing in more revenue than they will spend to maintain the neighborhood, and that's assuming they actually maintain the neighborhood (which they have not been). If they fail to spend the money on maintenance, the profit margins will be even higher.

This might strike some of you as surprising, yet it is important to understand that it is a consistent feature we see revealed in city after city after city all over North America. Poor neighborhoods subsidize the affluent; it is a ubiquitous condition of the American development pattern.

The Financial Productivity of BlightAs an example, consider what is probably our most famous case study here at Strong Towns, the Taco John's in my hometown of Brainerd, Minnesota, as described in "

The Cost of Auto Orientation."

The block on the left [above] has been labeled as blight. It's run down and neglected. The block on the right with the drive-through franchise restaurant is the same size, has the same amount of public infrastructure, and costs the same to provide ongoing service and maintenance. It just has a more modern development approach, one that is new.

This is poor and blighted versus affluent and modern. The cost to the city is the same but the poor block is worth 78% more and, subsequently, pays 78% more taxes to the city, than the affluent block.

Total value: $1.1 million

Total value: $618,000

This is no doubt surprising for those of you not used to seeing this kind of analysis. Most cities never do this kind of math let alone include it in a public policy conversation. Yet, it is a consistent pattern we have witnessed in cities of all sizes and geographies. Poor neighborhoods subsidize the affluent; it is a ubiquitous condition of the American development pattern.

Making the Best Investments

The best kind of financial investment is one with low risk and a guaranteed positive return. A money manager would do those kinds of investments all day, every day. They might be boring, but they are the foundation of wealth creation.

For cities that have done the math on the financial returns in their neighborhoods, the best investments are obvious. As I wrote in Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity:

The low-risk side of our public investment portfolio is as obvious as it is boring: Local governments must prioritize basic, routine maintenance in neighborhoods with high financial productivity (high value per acre).

For example, the downtown of Lafayette should never want for basic sidewalk maintenance. Those poor neighborhoods next to the downtown should never have streets full of potholes, overgrown ditches, or backed up pipes.

In Lafayette, these high-productivity neighborhoods are cash-flow positive. In cities more atrophied than Lafayette, the highest value-per-acre neighborhoods may not be profitable, but they have the best chance of becoming so, better than any other neighborhood in town. This is where our greatest wealth is; all we need to do is stabilize it.

Just take care of the neighborhood; it’s that simple.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting—as many professional city staff would be inclined to believe—that maintenance means big, transformative projects. That is what maintenance has come to mean; large projects built all at once to a finished state with efficiency as the value elevated above all others. What results is a short period where everything looks nice followed by a long period of decline that ends in an extended, sometimes permanent, state of dilapidation.

No, I’m describing maintenance that is more like the way the

Walt Disney Corporation maintains their theme parks: ongoing basic maintenance with an obsessive attention to detail. See a streetlight out: replace it. See a weed: pull it. See a crosswalk faded: repaint it. See a sidewalk broken: fix it. The poor neighborhoods that are already generating such wealth for the community need to be showered with love and attention. Financially, that’s the best approach.

Building Wealth in Poor NeighborhoodsBuilding wealth throughout our poorest neighborhoods will not be done at scale. There is no series of large projects, no massive centralized initiative, that will bring about real wealth creation without also inducing displacement.

Fortunately, the scale of the activity means that it’s the kind of thing any community can undertake, regardless of size, regardless of budget. Building wealth begins with the recognition that the best growth investments—the ones with the highest financial rate of return—address a real and urgent need experienced by people living in the neighborhood.

At Strong Towns, we’ve developed a

simple, four-step process for identifying this kind of opportunity and making it happen:

- Humbly observe where people in the community struggle.

- Ask the question: What is the next smallest thing we can do right now to address that struggle?

- Do that thing. Do it right now.

- Repeat.

The key to the first step is humility. Emptying our minds of as many preconceived notions about the problems and solutions in a place as possible, we humble ourselves to observe as a proxy for lived experience. We are trying to understand, from the perspective of those who struggle to use the city as it has been built, where those struggles are. A great way to observe is to walk with someone – literally treading the path with them – to understand how they struggle.

Observation is so much more powerful than even asking. When cities do surveys, focus groups, or public hearings, they are engaging in a format comforting to the decision-makers, not those they are seeking input from. Subsequently, public officials are not going to get the insight they really need. This is why I wrote that

most public engagement is worthless. If we want to identify the best investments, we need to get out of our comfort zone.

Where the first step requires humility, the second requires self-discipline. Instead of seeking the comprehensive solution, instead of trying to fix everything once and for all, we take our humble observation (which, if we’re truly humble, we must acknowledge is incomplete and maybe totally wrong) and just try to make that struggle a little bit better. We discipline ourselves to work in the smallest increment possible.

This isn’t because we are obsessed with the incremental. It’s because, as Jane Jacobs suggests, our neighborhoods must be a co-creation. By disciplining ourselves to act incrementally and iteratively, we allow people—our friends and neighbors living in the neighborhood—to react to the change and demonstrate to us, through their actions, where the next struggle is.

This is why, in the third step, we don’t form a committee. We don’t hire a consultant. We don’t pause eighteen months while our grant application is processed. We’ve humbly identified a struggle and then identified the next smallest thing we can do about it, so we just go out and do that thing. We make things better with what we have now. Right now.

And we’re comfortable with that action, not because it’s a comprehensive solution, and not because it totally eradicates struggles from our neighborhoods, but because we’re also committing to the fourth step, which is to repeat the process over and over and over. This is the process of co-creating, the way neighborhoods are made by everyone, for everyone.

We can make our cities financially strong while broadly increasing wealth and prosperity. That is the essence of a Strong Towns approach, one that every community has the capacity to put to work right now.