By Kea Wilson 12:00 AM EST on November 13, 2023

A 12-foot lane can expect roughly 50 percent more crashes than a 10-foot one. Yet many traffic engineers still pick the wider design.\

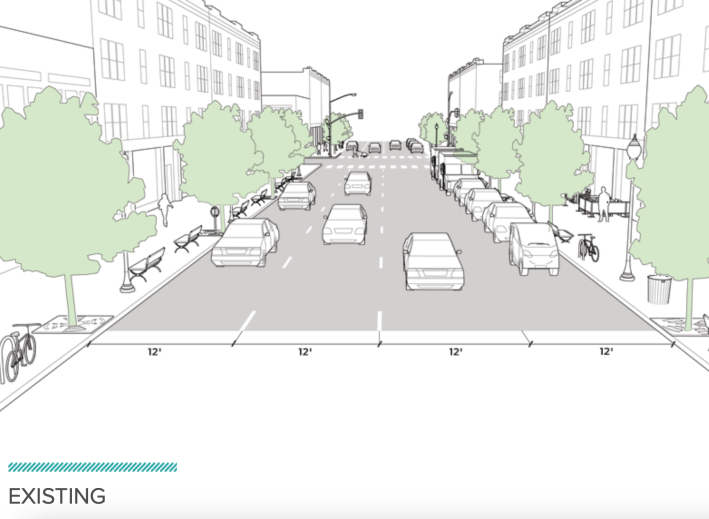

Photo: Matt Johnson|

The wide lanes of Salt Lake City make even big SUVs look diminutive.

Ten is plenty — and nine is even better.

The lightning-fast twelve-foot lanes that run down countless roads in U.S. neighborhoods are associated with a roughly fifty percent higher rate of crashes than nine-foot ones, a new study finds — but many state and national design guidelines are still encouraging engineers to build them based on the false assumption that wider is safer.

The finding is a result of a painstaking Johns Hopkins analysis of more than 1,100 non-interstate street sections in seven major U.S. cities — and amazingly, it may be the first time the relationship between lane width and safety has ever been comprehensively studied on such a large scale.

Roomy roads are proven to encourage faster, deadlier driving regardless of the speed limit, but previous research based on more limited data found less correlation between gargantuan lanes and high crash rates — with some researchers and engineers even arguing that narrow roads are more dangerous because they increase the possibility of “side friction” between cars. Unlike the 129-page Hopkins paper, though, those studies didn’t go street-by-street on Google Maps and use advanced machine learning to identify and control for all the other traffic-calming features that might be cutting crashes besides paint, including the number of lanes, the curvature of the road, and the presence of bike lanes, street trees and generous sidewalks.

Even in the absence of good data on lane width, though, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials’ Green Book — a national design guide known simply as “the Bible” among traffic engineers — has long recommended minimum lane widths between 10 and 12 feet on the high-volume arterial roads that criss-cross many U.S. neighborhoods. Many state street design standards, meanwhile, skew towards the upper bound of that range to avoid liability, based on the assumption that wider lanes are more “forgiving” of drivers’ mistakes; some streets in the researchers’ sample even clocked in as wide as 16 feet.

In Europe, by contrast, minimum lane widths typically vary between 8.2 and 10.6 feet — and that difference may be showing up in our higher fatality totals.

“When you compare the U.S. to other countries, the rate of traffic fatalities is almost 10 times higher here than it is for our European counterparts — and it’s just getting worse,” said Dr. Shima Hamidi, the principal investigator on the study. “The main reason is just car dependency. We’re designing our streets for more convenient and fast driving — and a big component of that is lane widths.”

Of course, all this new data will only confirm the suspicions of sustainable transportation advocates, many of whom have been calling for a re-striping revolution for decades.

Back in 2014, “Walkable City” author Jeff Speck named ditching the 12-foot lane “the number one most important thing that we have to fight for” in the battle to end America’s pedestrian death crisis — and he came to that conclusion based largely on a literature review that was conducted way back in 2003. (The Hopkins researchers didn’t look at how lane width affected pedestrian crash numbers, specifically, but a Transportation for America analysis found that non-interstate arterial highways — which frequently feature 12-foot lanes or wider — were the site of 70 percent of walking deaths in urban areas in 2020, despite the fact they make up just 15 percent of overall roadways.)

In the years since Speck made his bold proclamation, pedestrian deaths have increased a shocking 52 percent nationwide, but national lane width guidelines haven’t changed much.

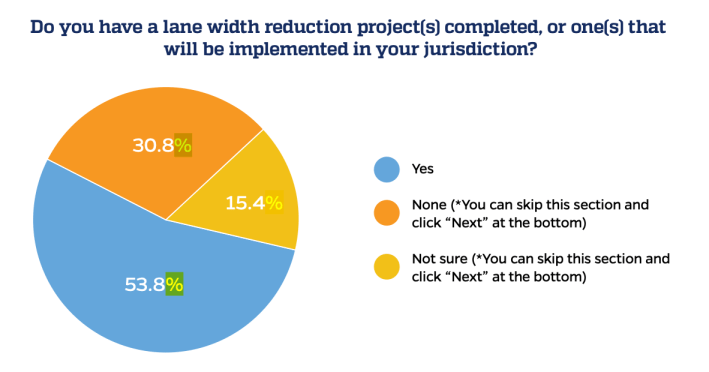

Hamidi points out that even communities that have created their own skinnier statewide standards aren’t necessarily losing lane width, either. The state of Vermont — which adopted the nine-foot minimum standard when it became the first state to depart from the Green Book in 1997 — hasn’t actually built any roads that narrow in the years since; only a slim majority of the 13 state DOTs the researchers surveyed (53.8 percent) said they had conducted any type of lane width reduction project at all.

From a survey of 13 state DOT representatives.Graphic: Johns Hopkins

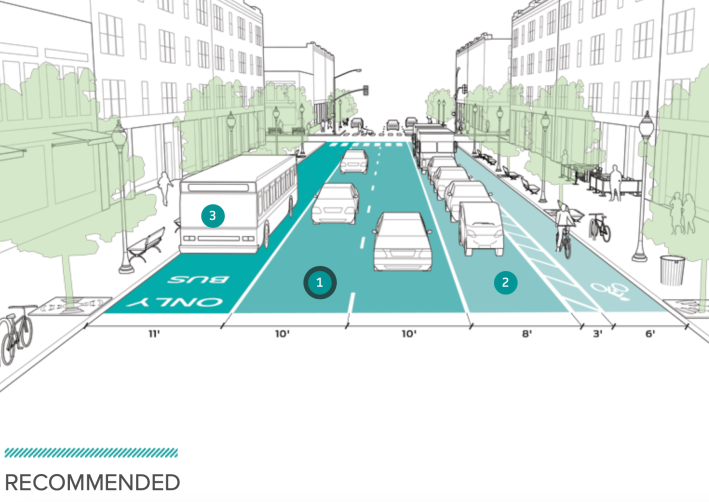

With this new data in hand, Hamidi is hopeful that states will finally feel empowered to be more aggressive about rethinking lane size, at least in areas that don’t truly need the extra space, like bus corridors and roads with frequent freight traffic. Because if they do, they’ll open up a conversation about what’s possible on their roads — not to mention a lot of new asphalt. She calls lane width reduction “probably the most cost efficient way to repurpose streets,” while simultaneously avoiding the thorny political challenges involved in removing a driving or parking lane completely.

“A three-foot difference per lane can make the difference between having a bike lane or not, or between having a sidewalk or not,” she added. “Lane width reduction is important, but equally important is thinking about how to best use that extra space that’s going to be freed up as a result … These things go hand by hand, and can lead to a world that is so much safer for pedestrians and cyclists.”

The post Study: Wide Lanes Are Deadlier — So Why Do Many DOTs Build Them Anyway? appeared first on Streetsblog California.

Kea Wilson@streetsblogkea

Kea Wilson has more than a dozen years experience as a writer telling emotional, urgent and actionable stories that motivate average Americans to get involved in making their cities better places. She is also a novelist, cyclist, and affordable housing advocate. She previously worked at Strong Towns, and currently lives in St. Louis, MO. Kea can be reached at kea@streetsblog.org or on Twitter @streetsblogkea. Please reach out to her with tips and submissions.

No comments:

Post a Comment

One of the objects if this blog is to elevate civil discourse. Please do your part by presenting arguments rather than attacks or unfounded accusations.