Denver gave people experiencing homelessness $1,000 a month. A year later, nearly half of participants had housing.

“Results showed 45% of participants secured housing, while $589,214 was saved in public service costs“

Full story here: Denver gave people experiencing homelessness $1,000 a month. A year later, nearly half of participants had housing. Business Insider

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool." - Richard Feynman

"You Yanks don't consult the wisdom of democracy; you enable mobs." - Australian planner

Wednesday, June 26, 2024

Denver gave people experiencing homelessness $1,000 a month. A year later, nearly half of participants had housing.

Friday, June 21, 2024

Writing congress to stop the wars

Dear Congressman Bera,

Your own foreign policy statement says you are supporting Ukraine to thwart "Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked and illegal invasion." You are missing the boat on this. John Mearsheimer's account of the history leading up to the "Special Military Operation" (here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JrMiSQAGOS4) lays out the generations-long provocations of Russia in excruciating detail. Portraying the US as some "innocent victim" simply doesn't pass the sniff test.

Another indicator of US aggression is its military budget. It's ten times larger than the Russian military budget.

Unfortunately, this aligns perfectly with the genocidal conquest of the North American continent at the origin of our country--diseases and wars annihilated 90% of the native populations.

And the US has repeatedly continued to be the aggressor overseas. Between 1798 and 1994 the US is responsible for 41 changes of government south of its borders, creating a constant stream of political and military refugees.

The economic attacks create even more refugees. In the wake of NAFTA, shipping lots of subsidized Iowa corn to Mexico led to a 34% decline in Mexican real, median income--a figure not seen in the US since the Great Depression.

Since World War II, there are just over 250 acts of military aggression worldwide. The US is responsible for 81% of those.

So you may tout "safety" or "leadership" as your reasons to support this glut of military imperialism from the US, but the US is increasingly isolated because of the depredations of its military.

It's well past time to stop this. Congress can de-fund the wars and sue for peace. Putin has repeatedly sought peace in Minsk and Istanbul, but the US has sabotaged those agreements.

The public wants peace, not some mealy-mouthed excuse for sending cluster munitions to bomb Gaza. Let's have our congressman implement the public's wishes.

--Your constituent

Monday, June 17, 2024

Restaurant industry claims that higher minimum wage led to lower employment are bunk

The fast-food industry claims the California minimum wage law is costing jobs. Its numbers are fake

Surrounded by fast-food workers in September, Gov. Gavin Newsom signs the bill raising the minimum wage in the industry to $20 an hour from $16.

(Damian Dovarganes / Associated Press)

By Michael HiltzikBusiness Columnist June 12, 2024 Updated 3:08 PM PT

The fast-food industry has been wringing its hands over the devastating impact on its business from California’s new minimum wage law for its workers.

Their raw figures certainly seem to bear that out. A full-page ad recently placed in USA Today by the California Business and Industrial Alliance asserted that nearly 10,000 fast-food jobs had been lost in the state since Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the law in September.

The ad listed a dozen chains, from Pizza Hut to Cinnabon, whose local franchisees had cut employment or raised prices, or are considering taking those steps. According to the ad, the chains were “victims of Newsom’s minimum wage,” which increased the minimum wage in fast food to $20 from $16, starting April 1.

— Business lobbyist Tom Manzo, touting misleading statistics

Something else the ad doesn’t tell you is that after January, fast-food employment continued to rise. As of April, employment in the limited-service restaurant sector that includes fast-food establishments was higher by nearly 7,000 jobs than it was in April 2023, months before Newsom signed the minimum wage bill.

Despite that, the job-loss figure and finger-pointing at the minimum wage law have rocketed around the business press and conservative media, from the Wall Street Journal to the New York Post to the website of the conservative Hoover Institution.

We’ll be taking a closer look at the corporate lobbyist sleight-of-hand that makes job gains look like job losses. But first, a quick trot around the fast-food economic landscape generally.

Few would argue that the restaurant business is easy, whether we’re talking about high-end sit-down dining, kiosks and food trucks, or franchised fast-food chains. The cost of labor is among the many expenses that owners have to deal with, but in recent years far from the worst. That would be inflation in the cost of food.

Newport Beach-based Chipotle Mexican Grill, for example, disclosed in its most recent annual report that food, beverages and packaging cost it $2.9 billion last year, up from $2.6 billion in 2022 — though those costs declined as a share of revenue to 29.5% from 30.1%. Labor costs in 2023 came to $2.4 billion, but fell to 24.7% of revenue from 25.5% in 2022.

At Costa Mesa-based El Pollo Loco, labor and related costs fell last year by $3.5 million, or 2.7%, despite an increase of $4.1 million that the company attributed to higher minimum wages enacted in the past as well as “competitive pressure” — in other words, the necessity of paying more to attract employees in a tight labor market.

Then there’s Rubio’s Coastal Grill. On June 3 the Carlsbad chain confirmed that it had closed 48 of its California restaurants, about one-third of its 134 locations. As my colleague Don Lee reported, Rubio’s attributed the closings to the rising cost of doing business in California.

There’s more to the story, however. The biggest expense Rubio’s has been facing is debt — a burden that has grown since the chain was acquired in 2010 by the private equity firm Mill Road Capital. By 2020, the chain owed $72.3 million, and it filed for bankruptcy. Indeed, in its full declaration with the bankruptcy court filed on June 5, the company acknowledged that along with increases in the minimum wage, it was facing an “unsustainable debt burden.”

The company emerged from bankruptcy at the end of 2020 with settlements that included a reduction in its debt load. Then came the pandemic, a significant headwind. Among its struggles was again its debt — $72.9 million owed to its largest creditor, TREW Capital Management, a firm that specializes in lending to distressed restaurant businesses. It filed for bankruptcy again on June 5, two days after announcing its store closings. The case is pending.

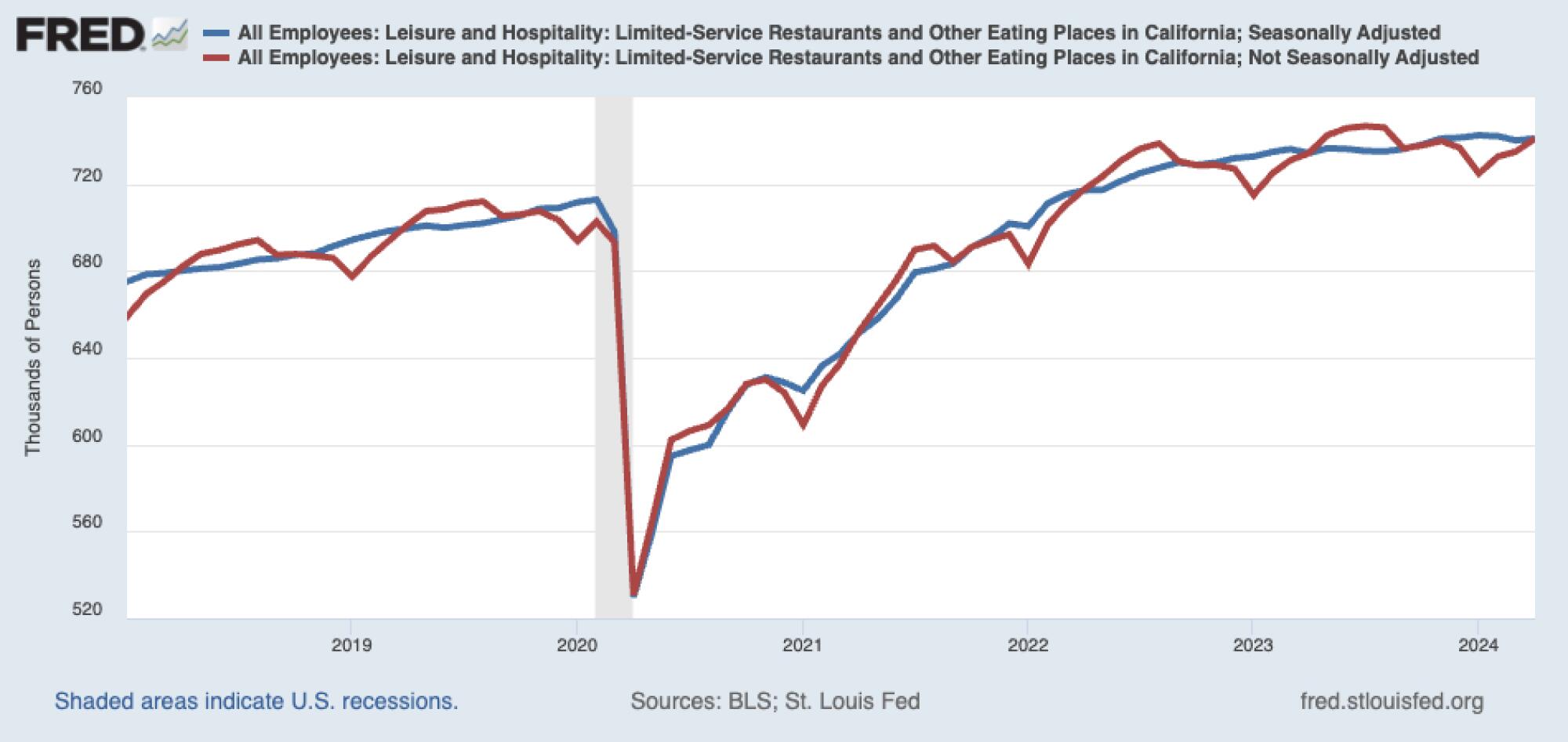

Fast-food and other restaurant jobs slump every year from the fall through January, due to seasonal factors (red line); seasonal adjustments (blue line) give a more accurate picture of employment trends. The sharp decline in 2020 was caused by the pandemic.

(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

It’s worth noting that high debt is often a feature of private-equity takeovers — in such cases saddling an acquired company with debt gives the acquirers a means to extract cash from their companies, even if it complicates the companies’ path to profitability. Whether that’s a factor in Rubio’s recent difficulties isn’t clear.

That brings us back to the claim that job losses among California’s fast-food restaurants are due to the new minimum wage law.

The assertion appears to have originated with the Wall Street Journal, which reported on March 25 that restaurants across California were cutting jobs in anticipation of the minimum wage increase taking effect on April 1.

The article stated that employment in California’s fast-food and “other limited-service eateries was 726,600 in January, “down 1.3% from last September,” when Newsom signed the minimum wage law. That worked out to employment of 736,170 in September, for a purported loss of 9,570 jobs from September through January.

The Journal’s numbers were used as grist by UCLA economics professor Lee E. Ohanian for an article he published on April 24 on the website of the Hoover Institution, where he is a senior fellow.

Ohanian wrote that the pace of the job loss in fast-food was far greater than the overall decline in private employment in California from September through January, “which makes it tempting to conclude that many of those lost fast-food jobs resulted from the higher labor costs employers would need to pay” when the new law kicked in.

CABIA cited Ohanian’s article as the source for its claim in its USA Today ad that “nearly 10,000” fast-food jobs were lost due to the minimum wage law. “The rapid job cuts, rising prices, and business closures are a direct result of Gov. Newsom and this short-sighted legislation,” CABIA founder and president Tom Manzo says on the organization’s website.

Here’s the problem with that figure: It’s derived from a government statistic that is not seasonally adjusted. That’s crucial when tracking jobs in seasonal industries, such as restaurants, because their business and consequently employment fluctuate in predictable patterns through the year. For this reason, economists vastly prefer seasonally adjusted figures when plotting out employment trend lines in those industries.

The Wall Street Journal’s figures correspond to non-seasonally adjusted figures for California fast-food employment published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (I’m indebted to nonpareil financial blogger Barry Ritholtz and his colleague, the pseudonymous Invictus, for spotlighting this issue.)

Figures for California fast-food restaurants from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis show that on a seasonally adjusted basis, employment actually rose in the September-to-January period by 6,335 jobs, from 736,160 to 742,495.

That’s not to say that there haven’t been employment cutbacks this year by some fast-food chains and other companies in hospitality industries. From the vantage point of laid-off workers, the manipulation of statistics by their employers doesn’t ease the pain of losing their jobs.

Still, as Ritholtz and Invictus point out, it’s hornbook economics that the proper way to deal with non-seasonally adjusted figures is to use year-to-year comparisons, which obviate seasonal trends.

Doing so with the California fast-food statistics gives us a different picture from the one that CABIA paints. In that business sector, September employment rose from a seasonally adjusted 730,000 in 2022 to 736,160 in 2023. In January, employment rose from 732,738 in 2023 to 742,495 this year.

Restaurant lobbyists can’t pretend that they’re unfamiliar with the concept of seasonality. It’s been a known feature of the business since, like, forever.

The restaurant consultantship Toast even offers tips to restaurant owners on how to manage the phenomenon, noting that “April to September is the busiest season of the year,” largely because that period encompasses Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, “two of the busiest restaurant days of the year,” and because good weather encourages customers to eat out more often.

What’s the slowest period? November to January, “when many people travel for holidays like Thanksgiving or Christmas and spend time cooking and eating with family.”

In other words, the lobbyists, the Journal and their followers all based their expressions of concern on a known pattern in which restaurant employment peaks into September and then slumps through January — every year.

They chose to blame the pattern on the California minimum wage law, which plainly had nothing to do with it. One can’t look into their hearts and souls, but under the circumstances their arguments seem more than a teensy bit cynical.

CABIA’s Manzo said by email that the alliance’s source for the job-loss statistic in its advertisement was the Hoover Institution, whose “work and credibility speaks for itself.”

He’s wrong about the source. Ohanian explicitly drew the number he cited in his Hoover Institution post from the Wall Street Journal; he didn’t do any independent analysis.

Ohanian acknowledged by email that “if the data are not seasonally adjusted, then no conclusions can be drawn from those data regarding AB 1228,” the minimum wage law. He said he interpreted the Wall Street Journal’s figures as seasonally adjusted and said he would query the Journal about the issue in anticipation of writing about it later this summer.

The author of the Wall Street Journal article, Heather Haddon, didn’t reply to my inquiry about why she appeared to use non-seasonally adjusted figures when the adjusted figures were more appropriate.

Ohanian did observe, quite properly, that the labor cost increase from the law was large and that “if franchisees continue to face large food cost increases later this year, then the industry will really struggle.” Fast-food companies already have instituted sizable price increases to cover their higher expenses, he observed. “The question thus becomes how sensitive are fast-food consumers to higher prices,” a topic he says he will be researching as the year goes on.

Michael Hiltzik

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Hiltzik has written for the Los Angeles Times for more than 40 years. His business column appears in print every Sunday and Wednesday, and occasionally on other days. Hiltzik and colleague Chuck Philips shared the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for articles exposing corruption in the entertainment industry. His seventh book, “Iron Empires: Robber Barons, Railroads, and the Making of Modern America,” was published in 2020. His forthcoming book, “The Golden State,” is a history of California. Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/hiltzikm and on Facebook at facebook.com/hiltzik.

Tuesday, June 11, 2024

China improves environment *and* economy simultaneously

This is a fascinating study that demonstrates how China has decoupled economic growth from environment degradation, and has now entered a phase where it can grow economically and have its environment improve at the same time.https://t.co/NjwGiv1Kbh

— Arnaud Bertrand (@RnaudBertrand) June 11, 2024

A team of researchers from…

Meanwhile:

Chinese carbon emissions have likely peaked, and are more than likely to decline

Monday, June 10, 2024

How 1978 Shifted Power In America And Laid The Groundwork For Our Current Political Moment (critical path history)

Joshua Green, January 12, 2024 [Talking Points Memo]

…There is a backstory that illuminates the Democratic Party’s embrace of finance in the years leading up to the [2008] crash — a story that begins in 1978. At the time, Democrats were still reliable partisans of the New Deal, but the steady economic progress of the American middle class was coming to a turbulent end. Jimmy Carter was president. He was struggling, without much success, to manage an economy buffeted by inflation, oil shocks and recessions — problems for which his party had no answers. A conservative countermovement of business groups and Republican politicians was beginning to gather force. One of history’s critical inflection points arrived that fall, when Wall Street made its first deep incursion into the Democratic Party in a way that would have lasting significance, although it passed mostly unnoticed at the time.

The great irony of this early conquest is that it began with Carter’s ambitious attempt to change the tax code to favor workers at the direct expense of Wall Street investors. Instead, Carter and his fellow reformers suffered a defeat so thorough that the financial lobby not only got to preserve its favorable tax treatment, but was able, with Democratic help, to rewrite the rules of the economy in a way that gave Wall Street an enduring structural advantage at the expense of the middle class — the opposite of what Carter had set out to do….

Soon after Carter launched his presidential bid, [Charls] Walker took over a sleepy financial industry trade group called the American Council on Capital Gains and Estate Taxation and rebranded it as the more exalted-sounding “American Council on Capital Formation,” a euphemism for the aggressive accumulation of wealth. Walker began pushing the idea that the economy’s productivity crisis could be solved if the government changed the way it induced business investment. Since the New Deal, the preferred method had been the investment tax credit, which rewarded companies for building factories. This generally satisfied labor interests, since factories produce jobs. The major business lobbies like the Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers liked the investment tax credit because many of their members were large industrial corporations. Carter’s plan to eliminate the capital gains preference didn’t threaten them.

But it terrified Wall Street. Walker’s project was to pull off a feat of legislative legerdemain by persuading lawmakers that the solution to U.S. economic malaise lay in shifting the government’s focus to encouraging capital formation — a move that would, its backers insisted, revitalize the supply side of the economy by spurring investment, unleashing entrepreneurial energies and turbocharging productivity. In practical terms, this meant preserving the biggest giveaway to investors in the tax code: the capital gains preference….

At Walker’s urging, several members of Congress, having fought off a capital gains increase, now turned around and started pushing for a tax cut. Wall Street brokerage houses led by Merrill Lynch and E.F. Hutton bombarded investors with mail telling them of the riches they stood to gain if rates were reduced. As the insurrection mounted over the spring, Ullman stopped work on the tax bill. But the momentum against Carter didn’t slow. On June 6th, California voters overwhelmingly passed the landmark ballot initiative Proposition 13, which slashed property taxes, made the cover of Time, and sparked a nationwide tax revolt. Dozens of anti-tax measures popped up in states across the country, helping shift the national mood in a more conservative direction and prefiguring the rise of Ronald Reagan.

In Washington, Carter’s reformers were overrun like Custer’s cavalry. Yet his humiliation wasn’t finished. In a remarkable feat of legislative jujitsu, Walker’s congressional allies prevailed upon Ullman to swap out the president’s tax reform bill for one of their own that, on every major front, was a repudiation of Carter’s principles. Instead of raising the capital gains rate to match income tax rates, the new bill slashed it, while adding a blizzard of new shelters and exemptions for the wealthy.…

Troubled by growing inequality, Carter had set out to rebalance in favor of the middle class the rewards government allots through the tax code. What he ended up with was a law that further empowered the very forces whose influence he sought to curb. Not only did the Revenue Act of 1978 cut corporate and capital gains taxes — redirecting investment from factories and equipment to financial instruments — but it also established the 401(k) retirement account, which channeled trillions of dollars more directly into the markets and undermined a pillar of middle-class security by eliminating employers’ obligation to provide pensions that ensured workers a stable retirement. If you go back to the Great Depression and trace the share of U.S. wealth held by the richest one percent of Americans, it falls steadily until 1978, whereupon it reverses and begins a steep ascent that continues to this day:

The law’s lasting impact on Democratic politics was that it ended a set of arrangements and a way of thinking about the economy that had held for four decades and replaced them with a new arrangement. Without quite realizing it or intending for it to happen, Carter’s signing the Revenue Act marked the beginning of the ascendance of finance capitalism as the major influence on Democratic policymaking. As organized labor declined, Wall Street assumed the role of senior partner in the party coalition. Democratic politicians, in turn, began emphasizing different priorities than during the Great Compression: fiscal austerity, soft labor markets, free trade with low-wage countries, and the further weakening of private-sector unions….

Taoist Theater / Teaching

From Keith Johnstone’s Impro (online here)

Anthony Stirling

I felt crippled, and 'unfit' for life, so I decided to become a teacher. I wanted more time to sort myself out, and I was convinced that the training college would teach me to speak clearly, and to stand naturally, and to be confident, and how to improve my teaching skills. Common sense assured me of this, but I was quite wrong. It was only by luck that I had a brilliant art teacher called Anthony Stirling, and then all my work stemmed from his example. It wasn't so much what he taught, as what he did. For the first time in my life I was in the hands of a great teacher.

I'll describe the first lesson he gave us, which was unforgettable and completely disorientating.

He treated us like a class of eight-year-olds, which I didn't like, but which I thought I understood—'He's letting us know what it feels like to be on the receiving end,' I thought.

He made us mix up a thick 'jammy' black paint and asked us to imagine a clown on a one wheeled bicycle who pedals through the paint, and on to our sheets of paper. 'Don't paint the clown,' he said, 'paint the mark he leaves on your paper!'

I was wanting to demonstrate my skill, because I'd always been 'good at art', and I wanted him to know that I was a worthy student. This exercise annoyed me because how could I demonstrate my skill? I could paint the clown, but who cared about the tyre-marks?

'He cycles on and off your paper,' said Stirling, 'and he does all sorts of tricks, so the lines he leaves on your paper are very interesting...'

Everyone's paper was covered with a mess of black lines—except mine, since I'd tried to be original by mixing up a blue. Stirling was scathing about my inability to mix up a black, which irritated me.

Then he asked us to put colours in all the shapes the clown had made. 'What kind of colours?' 'Any colours.'

*Yeah .. . but... er ... we don't know what colours to choose.'

'Nice colours, nasty colours, whatever you like.'

We decided to humour him. When my paper was coloured I found that the blue had disappeared, so I repainted the outlines black.

'Johnstone's found the value of a strong outline,' said Stirling, which really annoyed me. I could see that everyone's paper was getting into a soggy mess, and that mine was no worse than anybody else's—but no better.

'Put patterns on all the colours,' said Stirling. The man seemed to be an idiot. Was he teasing us? 'What sort of patterns?' 'Any patterns.'

We couldn't seem to start. There were about ten of us, all strangers to each other, and in the hands of this madman. 'We don't know what to do.' 'Surely it's easy to think of patterns.'

We wanted to get it right. 'What sort of patterns do you want?'

'It's up to you.' He had to explain patiently to us that it really was our choice. I remember him asking us to think of our shapes as fields seen from the air if that helped, which it didn't. Somehow we finished the exercises, and wandered around looking at our daubs rather glumly, but Stirling seemed quite unperturbed. He went to a cupboard and took out armfuls of paintings and spread them around the floor, and it was the same exercise done by other students. The colours were so beautiful, and the patterns were so inventive—clearly they had been done by some advanced class. 'What a great idea,' I thought, 'making us screw up in this way, and then letting us realise that there was something that we could learn, since the advanced students were so much better!' Maybe I exaggerate when I remember how beautiful the paintings were, but I was seeing them immediately after my failure. Then I noticed that these little masterpieces were signed in very scrawly writing. 'Wait a minute,' I said, 'these are by young children!' They were all by eight-year-olds! It was just an exercise to encourage them to use the whole area of the paper, but they'd done it with such love and taste and care and sensitivity. I was speechless. Something happened to me in that moment from which I have never recovered. It was the final confirmation that my education had been a destructive process.

Stirling believed that the art was 'in' the child, and that it wasn't something to be imposed by an adult. The teacher was not superior to the child, and should never demonstrate, and should not impose values: 'This is good, this is bad ...'

'But supposing a child wants to learn how to draw a tree?'

'Send him out to look at one. Let him climb one. Let him touch it.'

'But if he still can't draw one?'

'Let him model it in clay.'

The implication of Stirling's attitude was that the student should never experience failure. The teacher's skill lay in presenting experiences in such a way that the student was bound to succeed. Stirling recommended that we read the Tao Te Ching. It seems to me now that he was practically using it as his teaching manual. Here are some extracts:'...

The sage does not hoard. Having bestowed all he has on others, he has yet more; having given all he has to others, he is richer still. The way of heaven benefits and does not harm; the way of the sage is bountiful and does not contend.' (Translated by C. D. Lau, Penguin, 1969.)

I chose to teach in Battersea, a working-class area that most new teachers avoided—but I'd been a postman there, and I loved the place.

My new colleagues bewildered me. 'Never tell people you’re a teacher!' they said. 'If they find you're a teacher in the pub, they'll all move away!' It was true! I'd believed that teachers were respected figures, but in Battersea they were likely to be feared or hated. I liked my colleagues, but they had a colonist's attitude to the children; they referred to them as 'poor stock', and they disliked exactly those children I found most inventive. If a child is creative he's likely to be more difficult to control, but that isn't a reason for disliking him. My colleagues had a poor view of themselves: again and again I heard them say, 'Man among boys; boy among men' when describing their condition. I came to see that their unhappiness, and lack of acceptance in the community, came from a feeling that they were irrelevant, or rather that the school was something middle class being forcibly imposed on to the working-class culture. Everyone seemed to accept that if you could educate one of these children you'd remove him away from his parents (which is what my education had done for me). Educated people were snobs, and many parents didn't want their children alienated from them.

Like most new teachers, I was given the class no one else wanted. Mine was a mix of twenty-six 'average' eight-year-olds, and twenty 'backward' ten-year-olds whom the school had written off as ineducable. Some of the ten-year-olds couldn't write their names after five years of schooling. I'm sure Professor Skinner could teach even pigeons to type out their names in a couple of weeks, so I couldn't believe that these children were really dull: it was more likely that they were putting up a resistance. One astounding thing was the way cowed and dead-looking children would suddenly brighten up and look intelligent when they weren't being asked to learn. When they were cleaning out the fish tank, they looked fine. When writing a sentence, they looked numb and defeated.

Almost all teachers, even if they weren't very bright, got along reasonably well as schoolchildren, so presumably it's difficult for them to identify with the children who fail. My case was peculiar in that I'd apparently been exceptionally intelligent up to the age of eleven, winning all the prizes (which embarrassed me, since I thought they should be given to the dull children as compensation) and being teacher's pet, and so on. Then, spectacularly, I'd suddenly come bottom of the class—'down among the dregs', as my headmaster described it. He never forgave me. I was puzzled too, but gradually I realised that I wouldn't work for people I didn't like. Over the years my work gradually improved, but I never fulfilled my promise. When I liked a particular teacher and won a prize, the head would say: 'Johnstone is taking this prize away from the boys who deserve it!' If you've been bottom of the class for years it gives you a different perspective: I was friends with boys who were failures, and nothing would induce me to write them off as 'useless' or 'ineducable'. My 'failure' was a survival tactic, and without it I would probably never have worked my way out of the trap that my education had set for me. I would have ended up with a lot more of my consciousness blocked off from me than now.

I was determined that my classes shouldn't be dull, so I used to jump about and wave my arms, and generally stir things up—which is exciting, but bad for discipline. If you shove an inexperienced teacher into the toughest class, he either sinks or swims. However idealistic he is, he tends to clutch at traditional ways of enforcing discipline. My problem was to resist the pressures that would turn me into a conventional teacher. I had to establish a quite different relationship before I could hope to release the creativity that was so apparent in the children when they weren't thinking of themselves as 'being educated'.

I didn't see why Stirling's ideas shouldn't apply to all areas, and in particular to writing: literacy was clearly of great importance, and anyway writing interested me, and I wanted to infect the children with enthusiasm. I tried getting them to send secret notes to each other, and write rude comments about me, and so on, but the results were nil. One day I took my typewriter and my art books into the class, and said I'd type out anything they wanted to write about the pictures. As an afterthought, I said I'd also type out their dreams—and suddenly they were actually wanting to write. I typed out everything exactly as they wrote it, including the spelling mistakes, until they caught me. Typing out spelling mistakes was a weird idea in the early fifties (and probably now)—but it worked. The pressure to get things right was coming from the children, not the teacher. I was amazed at the intensity of feeling and outrage the children expressed, and their determination to be correct, because no one would have dreamt that they cared. Even the illiterates were getting their friends to spell out every word for them. I scrapped the time-table, and for a month they wrote for hours every day. I had to force them out of the classroom to take breaks. When I hear that children only have an attention span of ten minutes, or whatever, I'm amazed. Ten minutes is the attention span of bored children, which is what they usually are in school-hence the misbehaviour.

I was even more astounded by the quality of the things the children wrote. I'd never seen any examples of children's writing during my training; I thought it was a hoax (one of my colleagues must have smuggled a book of modern verse in!). By far the best work came from the 'ineducable' ten-year-olds. At the end of my first year the Divisional Officer refused to end my probation. He'd found my class doing arithmetic with masks over their faces—they'd made them in art class and I didn't see why they shouldn't wear them. There was a cardboard tunnel he was supposed to crawl through (because the classroom was doubling as an igloo), and an imaginary hole in the floor that he refused to walk around. I'd stuck all the art paper together and pinned it along the back wall, and when a child got bored he'd leave what he was doing and stick some more leaves on the burning forest.

My headmaster had discouraged my ambition to become a teacher: 'You're not the right type,' he said, 'not the right type at all.' Now it looked as if I was going to be rejected officially. Fortunately the school was inspected, and Her Majesty's Inspector thought that my class were doing the most interesting work. I remember one incident that struck him as amazing: the children screaming out that there were only three chickens drawn on the blackboard, while I was insisting that there were five (two were still inside the hen-house). Then the children started scribbling furiously away, writing stories about chickens, and shouting out any words they wanted spelt on the blackboard. I shouldn't think half of them had ever seen a chicken, but it delighted the Inspector. 'You realise that they're trying to throw me out,' I said, and he fixed it so that I wasn't bothered again.

Stirling's 'non-interference' worked in every area where I applied it: piano teaching for example. I worked with Marc Wilkinson, the composer (he became director of music at the National Theatre), and his tape recorder played the same sort of role that my typewriter had. He soon had a collection of tapes as surprising as the children's poems had been. I assembled a group of children by asking each teacher for the children he couldn't stand; and although everyone was amazed at such a selection method, the group proved to be very talented, and they learned with amazing speed. After twenty minutes a boy hammered out a discordant march and the rest shouted, 'It's the Japanese soldiers from the film on Saturday!' Which it was. We invented many games—like one child making sounds for water and another putting the 'fish' in it. Sometimes we got them to feel objects with their eyes shut, and got them to play what it felt like so that the others could guess. Other teachers were amazed by the enthusiasm and talent shown by these 'dull' children.

[p. 93]

Many teachers get improvisers to work in conflict because conflict is interesting but you don’t actually need to teach competitive behaviour; the students will already be expert at it, and it’s important that we don’t exploit the actors’ conflicts. Even in what seems to be a tremendous argument, the actors should still be co-operating, and coolly developing the action. The improviser has to understand that his first skill lies in releasing his partner’s imagination. What happens in my classes, if the actors stay with me long enough, is that they learn how their ‘normal’ procedures destroy other people’s talent. Then, one day they have a flash of satori--they suddenly understand that all the weapons they were using against other people they also use inwardly, against themselves.

Masks

[This is a passage difficult to excerpt because it’s all so amazing. The idea of masks “possessing” their wearer is very old but rediscovered in Johnstone’s theater work. He even refers to Voodoo possession, and African masks as ways of communicating with the spirit world. Chaplin reports donning his “tramp” costume spontaneously connected him with that famous character…who was silent.]

[p.148] Masks seem exotic when you first learn about them, but to my mind Mask acting is no stranger than any other kind: no more weird than the fact that an actor can blush when his character is embarrassed, or turn white with fear, or that a cold will stop for the duration of the performance, and then start streaming again as soon as the curtain falls. 'What's Hecuba to him?' asks Hamlet, and the mystery remains. Actors can be possessed by the character they play just as they can be possessed by Masks. Many actors have been unable to really 'find' a character until they put on the make-up, or until they try on the wig or the costume. We find the Mask strange because we don't understand how irrational our responses to the face are anyway, and we don't realise that much of our lives is spent in some form of trance, i.e. absorbed. What we assume to be 'normal consciousness' is comparatively rare, it's like the light in the refrigerator: when you look in, there you are ON but what's happening when you don't look in?

It's difficult to understand the power of the Mask if you've only seen it in illustrations, or in museums. The Mask in the showcase may have been intended as an ornament on the top of a vibrating, swishing haystack. Exhibited without its costume, and without a film, or even photograph, of the Mask in use, we respond to it only as an aesthetic object. Many Masks are beautiful or striking, but that's not the point. A Mask is a device for driving the personality out of the body and allowing a spirit to take possession of it. A very beautiful Mask may be completely dead, while a piece of old sacking with a mouth and eye holes torn in it may have tremendous vitality.

In its original culture, nothing had more power than the Mask. It was used as an oracle, a judge, an arbitrator. Some were so sacred that any outsider who caught a glimpse of them was executed. They cured diseases, they made women sterile. Some tribes were so scared of their power that they carved the eye holes so that the wearers could see only the ground. Some Masks were led on chains to keep them from

[p. 149]

attacking the onlookers. One African Mask had a staff, the touch of which was believed to cause leprosy. In some cultures dead people are reincarnated as Masks— the back of the skull is sliced off, a stick rammed in from ear to ear, and someone dances, gripping the stick with his teeth. It's difficult to imagine the intensity of that experience.

Masks are surrounded by rituals that reinforce their power. A Tibetan Mask was taken out of its shrine once a year and set up overnight in a locked chapel. Two novice monks sat all night chanting prayers to prevent the spirit of the Mask from breaking loose. For miles around the villagers barred their doors at sunset and no one ventured out. Next day the Mask was lowered over the head of the dancer who was to incarnate the spirit at the centre of a great ceremony. What must it feel like to be that dancer, when the terrifying face becomes his own?

We don't know much about Masks in this culture, partly because church sees the Mask as pagan, and tries to suppress it wherever it has the power (the Vatican has a museum full of Masks confiscated from the 'natives'), but also because this culture is usually hostile to trance states. We distrust spontaneity, and try to replace it by reason: The Mask was driven out of theatre in the same way that improvisation as driven out of music. Shakers have stopped shaking. Quakers don't quake any more. Hypnotised people used to stagger about, and trem ble. Victorian mediums used to rampage about the room. Education itself might be seen as primarily an anti-trance activity.

The church struggled against the Mask for centuries, but what can't be done by force is eventually done by the all-pervading influence of Western education. The US Army burned the voodoo temples in Haiti and the priests were sentenced to hard labour with little effect, but voodoo is now being suppressed in a more subtle way. The ceremonies are faked for tourists. The genuine ceremonies now last for a much shorter time.

I see the Mask as something that is continually flaring up in this culture, only to be almost immediately snuffed out. No sooner have I established a tradition of Mask work somewhere than the students start getting taught the 'correct' movements, just as they learn a phony 'Commedia dell' Arte' technique. The manipulated Mask is hardly worth having, and is easy to drive out of the theatre. The Mask begins as a sacred object, and then becomes secular and is used in festivals and in the theatre. Finally, it is remembered only in the feeble imitations of Masks sold in the tourist shops. The Mask dies when it is entirely subjected to the will of the performer.

Exercise

One suggestion to relieve the discomforts of aging, is yoga. All it

really takes is a yoga mat and a place to lay it down. There are lots of

routines on Youtube.

Rich vs. Poor Quote of the day

“The idea that the poor should have leisure has always been shocking to the rich.” — Bertrand Russell, “In Praise of Idleness,” Harper’s Magazine” (1932)

Monday, June 3, 2024

Tucker Carlson Interviews Jeffrey Sachs + Bonus Homelessness debunk

A long-ish video of Sachs basically refuting the idea that the US is some helpless victim of circumstance.

Preview:

Meanwhile, on the domestic front, here's a debunk of some of the myths surrounding homelessness.

Sunday, June 2, 2024

The crime and homelessness conundrum: Why enlarging County Jail isn't helpful

My email to Sacramento County:

Spending a billion dollars to enlarge the

County Jail is the epitome of a bad idea. True, the jail is full, but 60 - 80% of the

inmates are not convicted of anything, except being too poor to afford

bail. In Sacramento County it's not "innocent until proven guilty," it's

"guilty until proven wealthy." Waiting in jail for a court date almost

certainly means people who are already experiencing the stress of

poverty will have lost whatever job that kept them from being destitute

too. So it's doubly cruel to rely on caging more people. They are already poor

people, and will be poorer when they get out, even if they're judged to be innocent.

Never mind the

nearly-billion-dollar expense for the county to enlarge the jail, the

absence of any testimony about no-cash bail--like Illinois and Washington

D.C.--or supervised release is a huge error of omission.

Meanwhile, despite America's surplus of prisons, The Intercept

just exposed one principal reason jail expansion is endemic throughout

the country: Architectural firms specializing in incarceration are

making millions in profits for promoting jail

expansions.

The way the jail expansion boondoggle

occurs is that the architectural firms study future jail needs, which

somehow always require a jail expansion (surprise!). The Intercept

article doesn't feature the firm promoting Sacramento County's

jail expansion, but the pattern of selling expansion as a crime

"solution" is

identical.

As for homelessness: Richard

Nixon stopped the federal programs that built affordable housing in

1971, and, as it cut taxes on the wealthy roughly in half, the Reagan

administration also cut HUD's affordable housing budget by 75%. Is it

any surprise homelessness became such a problem?

A recent California study

discovered a significant majority of unhoused people became homeless

because of rent rises, and began seeking solace from their depressing condition in

drugs or mental illness only after they became homeless.

Wall Street firms recently became among the

largest homeowners in the country and relentlessly increased rents on the properties they acquired.

Incomes have not nearly kept pace with the rent rises. Zillow notes

that a "ratio of median rent to median income greater than 22% was

correlated with higher homelessness rates and a rent-to-income ratio

above 32% was associated with even sharper increases in homelessness."

A lack of resources is not at the root of homelessness, either. There are currently

more vacant homes than homeless people in the US. Rent control or

mandated rent reductions for vacant properties seems like a natural

solution, so what does public policy advocate? Building more homes! In

Vancouver, the Canadians curbed this kind of extortionate house hoarding

by taxing vacant properties.

Some public policymakers--Kevin

Kiley, Sue Frost, Rosario Rodriguez, etc.--believe "coddling

criminals"--e.g. Proposition 47's act of reducing felonies to

misdemeanors--leads to more crime, shoplifting, etc. Not so. Here's from KQED:

"Among our findings: The Numbers: Shoplifting numbers reported to law

enforcement have not risen since Proposition 47, but the rate of arrests

has fallen significantly." Yet Supervisor-elect Rodriguez promises more draconian penalties

like that's going to solve anything. Kevin Kiley is doubling down on a

repeal of Prop 47. Apparently one of the most difficult things to change

is one's mind.

It's

not for lack of funding that police make fewer arrests either. The US

population increased 42% from 1982 to 2017. During that same period,

spending on police increased by 187%. Police have the money. Heck, police now have armored personnel carriers.

On the

incarceration side, with only five percent of the world's population,

the US has 25% of its prisoners--five times the world's per-capita

average incarceration rate. That's seven times the per-capita rates in

Canada and France. So are Canada's and France's crime rates far worse

than the US? Nope. Slightly lower. Putting people in cages does not

prevent crime.

The bottom line (from "The Root Cause of Violent Crime Is Not What We Think It Is,"

NY Times) is "If you want policies that actually work, you have to

change the political conversation from 'tough candidates punishing bad

people' to 'strong communities keeping everyone safe.' Candidates who

care about solving a problem pay attention to what caused it. Imagine a

plumber who tells you to get more absorbent flooring but does not look

for the leak."

Despite

Hollywood's "copaganda” that says police

solve all crimes and only bad people go to jail, police solve only 15%

of crimes in California and roughly 50% of murders. To isolate one

community's experience, from 2010 to 2021, San Francisco's police budget

increased by 15%, yet total arrests declined by 41%, and although

reported offenses were up (+28%) crimes cleared (-33%) and total arrests

(-41%) both declined. Knowing this should make the public skeptical of

the effectiveness of those massive investments in punishment, or in

trusting police to do something different than "lock-'em-up" justice.

It's also

suggestive that San Francisco's police were slacking off despite their

increased funding

which amounts to a kind of extortion, hoping for even bigger police

budgets. ("Crime is up! Give us even more money!")

Several

of Sacramento's supervisors, and supervisor-elect Rodriguez want us to believe

crime is on the rise. However...(from an Attorney General's report entitled 2022 Crime in California)

"From 2017 to 2022, the property crime rate decreased 7.1 percent" and "The homicide rate decreased

5.0 percent in 2022..." So not all crime increased. Here's a graph that confirms that:

Note: Proposition 47 passed in 2014. Where's the surge in crimes?

And could treating people better, not putting them in cages, possibly be more effective in preventing crime and homelessness? Studies (here, here & here, for just a few examples) say better welfare prevents crime. Just giving poor people money is cheaper than harassing them with police, or taking them to emergency rooms.

Incarceration even has a terrible track record of success at treating drug addicts compared to actual medical treatment, and it's seven times more expensive than rehab. Unfortunately, programs that help people are vulnerable to sabotage, so when Oregon decriminalized drugs, policymakers left it to the police to implement their program. Unsurprisingly, police sabotage worked and the decriminalization was rolled back. The change would not be trivial if we were to decide treating people well would be better and cheaper than the practice of caging people.

Sadly, in my experience with the County--I sat on a Community Planning Advisory Council for nearly a decade,

among other things--I don't hold out much hope for the kind of

sustained, intelligent effort required to deal with the very real

problems of crime and homelessness. Instead, my bet is that the public will

see attempts at better marketing of policies that are bound to fail. You

know marketing...that's the kind of communication that tries to

persuade you that if you just buy this model of new car, you'll be able to date a

supermodel.

Mark Dempsey

Mark Twain's comment on current events.

“There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive’s new freedom away from him, and picks a quar...

-

Here's a detailed explanation by a Modern Monetary Theory founder, Stephanie Kelton. The bottom line: Social Security's enabling l...

-

Hey! It's for profit, so everything must be working as designed! What concerns me more than the height of peaks at this new point in SA...

-

“Only puny secrets need protection. Big discoveries are protected by public incredulity.” - Marshall McCluhan Although many people ...