...a pretty radical reinterpretation of religious tradition.

"The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool." - Richard Feynman

"You Yanks don't consult the wisdom of democracy; you enable mobs." - Australian planner

Thursday, February 28, 2019

Chris Hedges and Michael Hudson discuss debt forgiveness

...a pretty radical reinterpretation of religious tradition.

The State of California steps into the public banking revolution with SB 528

February 28, 2019

California

Public Banking Alliance at the Feb 4 public bank joint informational

hearing in Sacramento. Photo courtesy Public Bank East Bay

The bill SB 528,

introduced Feb 21 by CA State Senator Ben Hueso, would convert the

California I-Bank — a state revolving fund with a 20 year history — into

a true depository bank with a reserve account at the Federal Reserve.

PBI Chair Ellen Brown commented about the bill’s approach to convert the I-Bank:

“Adding a bank charter to the California I-Bank is a smart, commonsense plan. The I-Bank already does half the work of a bank: it issues loans in a market it understands well. After it obtains a bank charter it can do the other half: accept public funds as deposits and use the magic of leveraging its capital to expand the below-market loans for local infrastructure and development. Loans to municipalities and public entities have a very low risk of default. It will have low operational costs because there is no need for branches, tellers, or marketing.”

Converting

the I-Bank to a true depository bank would allow it to receive

deposits, manage accounts, and issue loans for its municipal clients.

The bank created by SB 528 would not provide direct retail services to

individuals but would continue to provide highly effective loan

guarantees from its Small Business Finance Center. Importantly the

reserve account of the new depository bank would not be subject to the

risk of bail-ins (loss of depositor funds) in the event of another

banking crisis. Public funds will be safer, unlike the public funds that

are currently deposited in privately owned banks.

Consumer advocate Ralph Nader said:

“This is a first step in ending muni bondage by taking public control of financing. Interest payments on municipal loans will be half those of private banks, and will be returned to the public, rather than transferred to the wealthiest 2% seeking to avoid personal income tax. Munis are a residual form of regressive taxation. Freeing California’s public monies from self-serving mismanagement by Wall Street fee-gougers is long overdue.”

The transformation of the IBank into a true bank was sponsored by the Democracy Collaborative of Washington, DC, with California efforts led by Dick Mazess of Santa Barbara.

The bill’s introduction followed a positive joint informational hearing on public banking held Feb 4 by the Banking and Finance & Local Government Committees. Sushil Jacob from the California Public Banking Alliance as well as Dick Mazess submitted formal testimonies for the hearing (read them here and here), while members of Public Bank East Bay and Public Bank Santa Rosa came to give public testimony.

Share this blog post with your friends! The Green New Deal: Just Focus on What We Do, Not How We Pay for It

By Marshall Auerback, a market analyst and commentator. Produced by Economy for All, a project of the Independent Media Institute

Extreme weather variations and increasingly dire scientific reports have spurred surprisingly robust policy proposals for a Green New Deal.

Rather admirably, the resolution sponsored by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) marks a significant break from the usual “small ball” incrementalist approach to politics adopted in D.C., reflecting the increasingly prevailing view that the next decade or two is make-or-break for planet Earth.

The sheer scale of the ambitious proposal—net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, clean air and water, married to traditional bread-and-butter progressive issues, such as a job guarantee and universal health care—have led to two predictable lines of attack: The first is that the program represents full-on socialism: a grab bag of the left’s favorite policies, “with everything from universal health care to a job guarantee draped under the mantle of environmentalism,” as a recent New York Times opinion piece explains. The second issue is how we are going to pay for it, given that the proposed Green New Deal resolution envisages costs that will run into the trillions to undertake this whole restructuring of the U.S. economy.

Shorn of ideological rhetoric, the answer to the second question is actually quite simple. We “pay” for these specific proposals much as we do with any government initiative: Congress appropriates the funds, and the government literally spends the money into existence. The key point here is that when a government issues a currency that is not backed by any metal or pegged to another currency (i.e., the currency is created via government order, or “fiat,” hence the term, “fiat currency”), then there is no reason why it should be constrained in its ability to finance its spending by issuing currency in the way it was, say, under a gold standard (in which the supply of gold held by each nation literally controlled its capacity to spend). By extension, taxes don’t actually “fund” the government, so much as they constrain overall expenditures in the economy. In essence, government spending adds new money to the economy, whereas the imposition of taxes takes some of that money out again. The constant addition and subtraction of these spending and taxing activities is how “fiscal policy” actually works (and the sequencing is actually the opposite of what is traditionally taught in most economics textbooks). Likewise, as the monopoly issuer of the currency, the U.S. government (via the Federal Reserve) establishes the rates at which we borrow (not “the market”). It therefore follows that a sovereign currency-issuing government, unlike a private company, does not have market-based costs of capital that set the opportunity cost of their activities. This is important to remember when you hear politicians outlining how certain policy goals are somehow “constrained” by borrowing costs (or a particular discount rate).

This is also why private sector concepts such as “internal rates of return” (IRR) or “return on equity” (ROE) are only relevant in macroeconomic policy terms, to the extent that the appropriated capital is used as productively as possible to mitigate possible inflationary pressures, as opposed to whether this spending ultimately generates a profit or loss for the government. To put it another way, even if the government’s “balance sheet” is adversely affected by poorly conceived and executed policy choices, these mistakes have no bearing on whether the United States, as the currency issuer, has the “fiscal capacity” to meet any future crisis (in contrast to a private firm, which can’t afford to misuse its finite capital resources, lest cumulative losses drive it out of business). As such, costs and benefits must be measured largely in social terms, rather than financial terms, even as we acknowledge that the damage to GDP from the negative effects of climate change can be substantial.

Note that although there is no financial constraint on the ability of a sovereign nation to deficit spend, this does notmean that there are no real resource constraints on government spending; this is the real concern that should guide policy, not financial constraints. If government spending pushes the economy beyond full capacity, inflation will result. A government can create all of the currency it likes, but there are finite supplies of natural resources, labor, and other productive assets that form the backbone of an economy. Put another way, money is not scarce, but real resources can be. So if government spending does not add to the economy’s productive capacity, then excessive expenditures will almost certainly become inflationary, and that does represent a legitimate constraint. That is why the main focus of the Green New Deal should be on how the money is spent, rather than how the program is to be funded.

So in assessing how appropriated funds under a Green New Deal are spent, the decarbonization of the U.S. economy must be constructed with a view toward other broad social goals, which is why the Markey/Ocasio-Cortez resolution incorporates so many additional features that at first glance do not deal solely with environmental issues (a complaint recently made by Speaker Nancy Pelosi). A job guarantee, for example, must be a germane consideration in contemplating a substantial reduction and ultimately a full-on elimination of the fossil fuels industry. This not only means the hundreds of thousands of workers actually involved in the extraction, production, and distribution of oil, gas, coal, etc., but also the administrative and support jobs connected to these industries, and the communities adversely impacted by the resultant job losses.

To give some idea of the scale of potential jobs at risk here, a recent U.S. Energy and Employment report from 2017 estimates that there are “about 2.3 million jobs in Transmission, Distribution, and Storage, with approximately 982,000 working in retail trade (gasoline stations and fuel dealers) and another 830,000 working across utilities and construction.” It is virtually impossible to contemplate the implementation of a Green New Deal if it is not accompanied holistically by policies that address the potential job disruption. We don’t want to have this debate framed yet again within the sterile paradigm of “jobs vs. environment,” which is a political non-starter.

The Canadian Labor Congress, among others, has enumerated a number of possible jobs to which the displaced workers could transition. These jobs would include “the retrofitting of buildings for energy conservation, the retraining of workers to become energy auditors, developing renewable energy sources, promoting sustainable transport systems, supporting community-based sustainable industries, community revitalization projects, moving towards a complete waste recycling program, and creating a publicly owned infrastructure that will manage in the public good.”

There’s no question that a properly revived manufacturing sector would also lead to a revived working and middle class, because as the economist Seymour Melman explained, high-skill manufacturing leads to a process of economic growth that gives workers more power, economically and within the firm—even with mechanization and automation. To be sure, historically, manufacturing has often been associated with “dirty” industries. According to Jon Rynn, a fellow at the CUNY Institute of Urban Systems, emissions from manufacturing account for about 28 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. Once the electrical system is renewable, however, a substantial amount of these emissions is eliminated, because almost all industrial machinery uses electricity. So if the electricity is clean, manufacturing can expand without worsening the climate problem. Needless to say, this will require significant investments in energy efficiency alongside rapid decarbonization of power sources for as much of the economy as possible.

The broader question of inequality must also be tackled. We live in a world where things are interdependent. Hence, the whole concept of a just transition to an environmentally sustainable economy can only be adequately addressed when it is wrapped in a broader set of policies designed to help most Americans, which raises distributional questions that are part of the broader problem of today’s highly unequal economy. As the economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman have documented, tax data in the United States illustrates that top 0.1 percent now hold 22 percent of the total wealth in the United States—the same amount as the bottom 90 percent. This takes us back to levels of economic distribution that existed more than 100 years ago, when we barely had cars, unions were virtually non-existent, and social welfare provision was minuscule. Simply believing that creating a whole bunch of “clean tech” jobs in and of itself will resolve this problem is disingenuous, which is why the Markey/Ocasio-Cortez resolution specifically addresses the broader issue of economic inequality.

Failure to address the inequality question exacerbates the inflationary problem, because when increasing amounts of GDP are directed toward those with the highest savings propensities (i.e., the 1 percent), it means that the economy doesn’t grow as efficiently. This matters when we are addressing a genuine national emergency, such as climate change (as opposed to the faux “national emergency” related to Trump’s southern border wall).

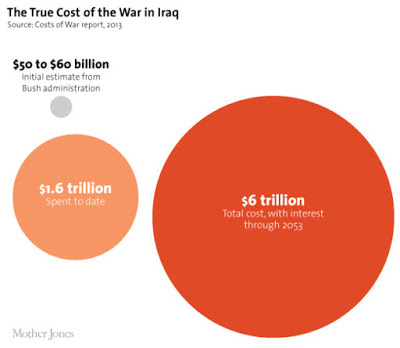

The scale of the spending shouldn’t scare people. At $2 trillion a year, that’s around 10 percent of a $20 trillion economy. Put another way, the American government has spent greater sums in its Afghanistan and Iraq wars with no lasting productive benefit accruing to the U.S. economy (to say nothing of the social costs and global environmental degradation). By way of comparison, as Jon Rynn writes, “the Federal government paid for most of the machinery used to create the military equipment during World War II, and the corporations bought the factories for pennies on the dollar after the war ended.” To put it another way, the federal government did not “record a profit” on the sale of these assets, but the “return” came in the form of much of the industrial machinery that was the basis for the shared prosperity of the post-WWII boom, a period of unparalleled “sharedprosperity” (emphasis added) for the United States.

We have to make choices, but the idea that we can’t make the right choices based on funding concerns is ridiculous. However, the policy goal embodied in the Green New Deal must be part of a broader policy framework, much as Franklin Delano Roosevelt ultimately conceived of his Economic Bill of Rights (which featured a government-funded health care provision) as an extension of the original New Deal. After all, the Green New Deal is as much about enhancing “human capital”—that is, increasing the wealth-generating capability of people—as it is about “physical capital,” the machinery and systems that are physical in nature. Speaking about one without the other is as misconceived as speaking about a tree outside the context of the forest in which it grows. Remember that, the next time someone dismisses the Green New Deal as a grab bag of policies designed to ensure a communist-style capture of the commanding heights of the economy.

Wednesday, February 27, 2019

Krugman vs Kelton on the fiscal-monetary tradeoff

26 February, 2019 at 16:01 | Posted in Economics |

Paul Krugman is back again telling us that he doesn’t really want to spend time on arguing about MMT — and then goes on complaining that well-known MMTer Stephanie Kelton says things “obviously indefensible.” What has especially irritated the self-proclaimed ‘conventional’ Keynesian is that Kelton “seems to claim that expansionary fiscal policy … will lead to lower, not higher interest rates.”

Paul Krugman is back again telling us that he doesn’t really want to spend time on arguing about MMT — and then goes on complaining that well-known MMTer Stephanie Kelton says things “obviously indefensible.” What has especially irritated the self-proclaimed ‘conventional’ Keynesian is that Kelton “seems to claim that expansionary fiscal policy … will lead to lower, not higher interest rates.”

Now, the logic behind Krugman’s “conventional Keynesian” loanable-funds-IS-LM-theory is that if the government is going to pursue an expansionary fiscal policy it will have to borrow money and thereby increase the demand for loanable funds which will — “other things equal” — lead to higher interest rates and less private investment.

The loanable funds theory is in many regards nothing but an approach where the ruling rate of interest in society is — pure and simple — conceived as nothing else than the price of loans or credits set by banks and determined by supply and demand in the same way as the price of cars and raincoats.

It is a beautiful fairy tale, but the problem is that banks are not barter institutions that transfer pre-existing loanable funds from depositors to borrowers. Why? Because, in the real world, there simply are no pre-existing loanable funds. Banks create new funds — credit — only if someone has previously got into debt! Banks are monetary institutions, not barter vehicles.

In the traditional loanable funds theory — as presented in Krugman’s own textbooks — the amount of loans and credit available for financing investment is constrained by how much saving is available. Saving is the supply of loanable funds, investment is the demand for loanable funds and assumed to be negatively related to the interest rate.

The loanable funds theory in the ‘New Keynesian’ approach means that the interest rate is endogenized by assuming that Central Banks can (try to) adjust it in response to an eventual output gap. This, of course, is essentially nothing but an assumption of Walras’ law being valid and applicable, and that a fortiori the attainment of equilibrium is secured by the Central Banks’ interest rate adjustments. From a Keynes-Minsky-MMT point of view, this can’t be considered anything else than a belief resting on nothing but sheer hope.

The traditional loanable funds theory is that it assumes that saving and investment can be treated as independent entities. This is seriously wrong:

The classical theory of the rate of interest [the loanable funds theory] seems to suppose that, if the demand curve for capital shifts or if the curve relating the rate of interest to the amounts saved out of a given income shifts or if both these curves shift, the new rate of interest will be given by the point of intersection of the new positions of the two curves. But this is a nonsense theory. For the assumption that income is constant is inconsistent with the assumption that these two curves can shift independently of one another. If either of them shifts, then, in general, income will change; with the result that the whole schematism based on the assumption of a given income breaks down … In truth, the classical theory has not been alive to the relevance of changes in the level of income or to the possibility of the level of income being actually a function of the rate of the investment.

Savers and investors have different liquidity preferences and face different choices — and their interactions usually only take place intermediated by financial institutions. This, importantly, also means that there is no ‘direct and immediate’ automatic interest mechanism at work in modern monetary economies. What happens at the microeconomic level is not always compatible with the macroeconomic outcome. The ‘atomistic fallacy’ has many faces — loanable funds is one of them.

We have to free ourselves from the loanable funds theory — and scholastic gibbering about ZLB — and start using good old Keynesian fiscal policies. Keynes — as did Lerner, Kaldor, Kalecki, and Robinson — showed that it was possible to promote economic growth with an “appropriate size of the budget deficit.” The stimulus a well-functioning fiscal policy aimed at full employment may have on investment and productivity does not necessarily have to be offset by higher interest rates.

Tuesday, February 26, 2019

Former US President Carter: Venezuela’s Electoral System “Best in the World”

“As a matter of fact, of the 92 elections that we’ve monitored, I would say the election process in Venezuela is the best in the world.”

Region: Latin America & Caribbean

First published in September 2012 prior to Venezuela’s October 2012 presidential elections, in which Chavez was reelected.

***

Former US President Jimmy Carter claimed Venezuela’s electoral system is “the best in the world” (agencies).

Mérida, 21st September 2012 (Venezuelanalysis.com) – Former US President Jimmy Carter has declared that Venezuela’s electoral system is the best in the world.

Speaking at an annual event last week in Atlanta for his Carter Centre foundation, the politician-turned philanthropist stated,

“As a matter of fact, of the 92 elections that we’ve monitored, I would say the election process in Venezuela is the best in the world.”

Venezuela has developed a fully automated touch-screen voting system, which now uses thumbprint recognition technology and prints off a receipt to confirm voters’ choices.

Real News 2012 Report on Venezuela’s electoral system

In the context of the Carter Centre’s work monitoring electoral processes around the globe, Carter also disclosed his opinion that in the US “we have one of the worst election processes in the world, and it’s almost entirely because of the excessive influx of money,” he said referring to lack of controls over private campaign donations.

The comments come with just three weeks before Venezuelans go to the polls on 7 October, in a historic presidential election in which socialist incumbent President Hugo Chavez is standing against right-wing challenger Henrique Capriles Radonski of the Roundtable of Democratic Unity (MUD) coalition.

The comments come with just three weeks before Venezuelans go to the polls on 7 October, in a historic presidential election in which socialist incumbent President Hugo Chavez is standing against right-wing challenger Henrique Capriles Radonski of the Roundtable of Democratic Unity (MUD) coalition.

Chavez welcomed Carter’s comments, stating yesterday that

“he [Carter] has spoken the truth because he has verified it. We say that the Venezuelan electoral system is one of the best in the world”.

Chavez also reported that he had had a forty minute conversation with the ex-Democrat president yesterday, and said that Carter, “as Fidel [Castro] says, is a man of honour”. The Carter Centre has recently confirmed it will not send an official delegation to accompany the presidential election, but may have officials observe the process on an individual basis.

Meanwhile, the Union of South American Nations (Unasur) electoral accompaniment delegation arrived yesterday in Venezuela.

The delegation’s head, former Argentinian vice-president Carlos Alvarez, mentioned that this was the Unasur’s first electoral observation mission, and that “for us it’s fundamental to consolidate our democracies, because it’s taken us a lot of struggle, effort and time to establish [democracy] in our countries”.

In press comments after meeting with officials from Venezuela’s National Electoral Council (CNE) Alvarez declared that based on his experience of electoral observation in South America, ”Venezuela has one of the most advanced electoral systems in the region and the continent, that grants a great deal of confidence and transparency”.

Meanwhile, secretary of the MUD, Ramón Guillermo Aveledo, accused the CNE yesterday of being “biased”, and said that it doesn’t adhere to the National Constitution nor electoral law. In an interview with opposition TV station Globovision, he clarified his opinion that “we [the MUD] trust the voting system” but that CNE officials “have a preference” for the government.

The CNE has issued warnings regarding both the MUD and Chavez’s Carabobo Command for infringements of campaign rules relating to electoral publicity and advertising space.

Pro-Chavez sources have speculated that the opposition is planning not to recognise the CNE results in the likely event of a Chavez victory on 7 October. In July, Chavez and Capriles signed an accord by which both agreed to recognise the result announced by the CNE.

How Much Will It Cost to Address Climate Change? Pennies Compared to the Alternative

By Thomas Neuburger. Originally published at DownWithTryanny!

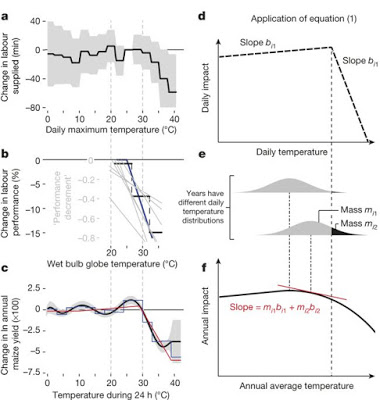

Economic growth and global warming, Figure 1 from a paper studying “Global nonlinear effect of temperature on economic production” (link below). “Non-linear” in this case means “at what warming point do economies tend to ‘fall off a cliff'”? It’s not the same point for all economies, but the non-linearity is obvious. (For conversion in charts a, b, and c, 20°C = 68°F, and 30°C = 86°F. Click to enlarge.)

The cost of addressing climate change is much in the news these days, thanks to the Ocasio-Cortez Green New Deal (GND) proposal. Everyone seems to want to know how much it will cost. Too much, according to the editors at Forbes. “The Green New Deal Would Cost a Lot of Green,” they warn us, and the editors at Bloomberg want us to know that “The Green New Deal Is Unaffordable.”

These headlines tell you they measure cost in terms of lost profit, not lost wages, since no one at Forbes or Bloomberg wants to see wages rise. Nor do they consider lost lives.

Green New Deal advocates assure us that indeed we can pay for it, partly because of increased productivity (it will put a lot of people to work, FDR-style) and partly because the economy can simply absorb the influx of new money without the need for high “pay for it” taxes, just as the economy is absorbing the multi-trillion cost of the Iraq War and President Trump’s tax cuts. When elites and the wealth they serve want something expensive, they get it, and no one bothers to make them “pay for it” later.

See this Huffington Post article, “We Can Pay For A Green New Deal,” by Stephanie Kelton, Andres Bernal and Greg Carlock for the gist of the “yes, it’s affordable” argument.

Both statements are true, of course. Any attempt to really mitigate climate change — make the damage less, as opposed to merely adapting to the crisis — will cost “a lot of green.” And yes, the economy can absorb the additional spending, allowing taxes to be used only as an economic cooling device (if and as needed), not as a prohibitory “pay for it” device.

Measuring the Wrong Variable

But few are focusing on the real measurable — not what it will cost economically to address the problem, but what it will cost economically to not address the problem. “Cost economically” here means exactly and only what the people at Forbes and Bloomberg think it means — How does economic activity slow when atmospheric temperature rises? How are profits and wealth affected? This analysis looks at no other factors affecting the economy, such as the cost of recovery from super-storms.

One of those who did address the economic cost of not dealing with climate change is Solomon Hsiang, professor of public policy at UC Berkeley and coauthor of a little-noticed 2015 paper, “Global nonlinear effect of temperature on economic production.” A link to the Nature abstract is here; a link to the paper itself is here (pdf).

The abstract begins this way (notes are linked in the original):

The language of the abstract is a little confusing for a lay reader, so let me explain. In essence, the question they’re studying is this: Are macroeconomies (economies of whole nations) affected by atmospheric warming, contrary to what is reported? If so, are those effects linear (gradual and along a straight line) or non-linear (sudden and precipitous at certain thresholds)?

In other words, do national economies “drop off a cliff” at certain levels of increased atmospheric heating? The graph at the top, taken from the paper, shows the answer is yes.

The authors conclude (my emphasis):

We show that overall economic productivity is non-linear in temperature for all countries, with productivity peaking at an annual average temperature of 13 °C [56°F] and declining strongly at higher temperatures. The relationship is globally generalizable, unchanged since 1960, and apparent for agricultural and non-agricultural activity in both rich and poor countries.

Note that this is a study of the past, not the future. In other words, the study looked at real-world consequences of warming that has already occurred, not projected consequences using economic models only. Thus this forward-looking conclusion: “If future adaptation mimics past adaptation, unmitigated warming is expected to reshape the global economy by reducing average global incomes roughly 23% by 2100 and widening global income inequality, relative to scenarios without climate change.”

Widening global wealth inequality means that some nations will do better than others — at first. An article covering a subsequent talk by Dr. Hsiang put it this way:

That decrease in economic output will hit the poorest 60 percent of the population disproportionately hard, said Hsiang. In doing so, it will surely exacerbate inequality, as many rich regions of the world that have lower average annual temperatures, such as northern Europe, benefit from the changes. Hotter areas around the tropics, including large parts of south Asia and Africa, already tend to be poorer and will suffer.

A graph printed with the article indicates the eastern seaboard of the United States and northern Europe, among other places, will have improved economies (click through to see it).

But the conclusion that the East Coast and northern Europe will thrive economically is deceptive, since the study was limited to the economic effects of warming. What about the physical effects? For example, the population of the East Coast of the U.S. will at some point suffer numerous super-storms, sea level rise and the shoreline erosion that always accompanies it.

Put simply, at some point cities on both coasts will have to be moved inland as the land they sit on erodes into the ocean. How far inland? I wouldn’t want to be the planner that has to figure that out, since you only want to have to do it once.

The East Coast is home to about 120 million people. The total U.S. population is between 300–350 million people. More than a third of all U.S. citizens will be forced to relocate away from the Atlantic shore. What’s the cost of that?

As to northern Europe, if the thermohaline current (the Gulf Stream) is drastically altered by fresh water melt from Greenland, northern Europe — England, for example — will freeze like Canada in the winter, whose latitude it shares. Will England thrive economically in that scenario?

How Much Will It Cost Not to Mitigate Climate Change? $17 Trillion Per Year in Economic Loss Alone

So what’s the economic cost of not responding to global warming? According to the paper, the bottom line is this. Global GDP (called Global World Product, or GWP) was estimated between $70 and $80 trillion about five years ago. Thus, by this paper’s (highly conservative) estimates, the economic loss that results from willfully ignoring climate change will be roughly $17 trillion per year by 2100, a sum that doesn’t include the additional cost of wars, famines, droughts, plagues, epidemics, and “national emergencies” of various flavors and stripes.

Can we afford, economically, not to address climate change now? The answer, of course, is no.

Yet once more the pathological among us have us asking the wrong questions. All they want to know is, will their own wealth be affected? Will they still keep their billions? Will they die poorer than they are today?

The question we should be asking is, will the rest of us die poorer — and sooner — if our first priority is protecting the wealth of the wealthy?

The answer, of course, is yes.

Saturday, February 23, 2019

Instanbul, not Constantinople, treats pets well

VIDEO: 🇹🇷 In Istanbul, stray cats and dogs are not chased from the streets -- instead authorities feed them and give them veterinary care, not only improving their health but that of residents who come into contact with them pic.twitter.com/PZPt4hqeVI— AFP news agency (@AFP) February 18, 2019

And yes, music, too:

Thursday, February 21, 2019

Thursday, February 14, 2019

Hillary's campaign was not NORMAL

I’m sorry I lack the credentials to make this case more forcefully, but as a veteran of political campaigns from local to presidential, nothing about Hillary Clinton’s campaigns is NORMAL.

She doesn’t run campaigns that are organized like actual political campaigns. She instead establishes a cult of personality that is direct at odds with classic strategies for winning elections.

Campaigns fall apart after each election. Cults persist. The Clintonites are still fighting to cover up what happened in 2016. There’s nothing normal about that. So long as the party and the Clintonites are not held accountable, we will continue to struggle with bad choices at the ballot box.

(from nakedcapitalism.com's comments)

Wednesday, February 13, 2019

MMT Baffles Krugman

NY Times columnist economist Paul Krugman claims MMT misses some obvious economic problems. He says it really originated with Abba Lerner's Functional Finance, and writes about it here and here. MMT economist, Stephanie Kelton, responds here.

Here's what Krugman gets wrong:

"But you don’t have to be a deficit scold to suggest that progressives should be thinking about how to pay for their policies. ....some progressives appear to believe means that they don’t need to worry about how to pay for their initiatives." -- Krugman

...and he basically criticizes MMT for believing their spending wouldn't raise the specter of inflation, and higher Fed interest rates, effectively "crowding out" private investment, ignoring that shortages of goods and services are really what initiate inflation (e.g. oil in the U.S. in the '70s, or food in Zimbabwe).

1. Taxes manage demand, they do not provision the government. If they really provisioned Federal programs, where would taxpayers get the dollars they use if government doesn't spend them out into the economy first?...

Then...uncontroversially, even taxes paying for Medicare for all would cost half what we pay private insurance now.

2. Krugman also cites "Okun's Law" about unemployment, but that law does not anticipate a job guarantee (JG). which the Green New Deal proposes. Short of a JG, the current labor surplus, and downward pressure on wages will continue to dominate the employment scene.

What remains stunning is Krugman's continuing embrace of his own DSGE/pseudo-Keynesianism. Hicks himself, the inventor of IS/LM--a calculation frequently cited by Krugman--withdrew his support of that tool because, he confessed, it was *not* Keynesian. Incidentally, the "E" in DSGE signifies an assumed equilibrium...not exactly what happened in 2007-8.

Krugman's neoclassical economics' advice not only did not anticipate the Great Recession--as MMT did--it has put us in the perilous position of blessing the rentiers as the "productive" members of society--exactly the opposite of classical economics!

What is astonishing is how far pundits like Krugman will go to avoid admitting their own mistakes. They're too busy picking the mote out of MMT's eye to deal with the beam in their own.

Here's what Krugman gets wrong:

"But you don’t have to be a deficit scold to suggest that progressives should be thinking about how to pay for their policies. ....some progressives appear to believe means that they don’t need to worry about how to pay for their initiatives." -- Krugman

...and he basically criticizes MMT for believing their spending wouldn't raise the specter of inflation, and higher Fed interest rates, effectively "crowding out" private investment, ignoring that shortages of goods and services are really what initiate inflation (e.g. oil in the U.S. in the '70s, or food in Zimbabwe).

1. Taxes manage demand, they do not provision the government. If they really provisioned Federal programs, where would taxpayers get the dollars they use if government doesn't spend them out into the economy first?...

Then...uncontroversially, even taxes paying for Medicare for all would cost half what we pay private insurance now.

2. Krugman also cites "Okun's Law" about unemployment, but that law does not anticipate a job guarantee (JG). which the Green New Deal proposes. Short of a JG, the current labor surplus, and downward pressure on wages will continue to dominate the employment scene.

What remains stunning is Krugman's continuing embrace of his own DSGE/pseudo-Keynesianism. Hicks himself, the inventor of IS/LM--a calculation frequently cited by Krugman--withdrew his support of that tool because, he confessed, it was *not* Keynesian. Incidentally, the "E" in DSGE signifies an assumed equilibrium...not exactly what happened in 2007-8.

Krugman's neoclassical economics' advice not only did not anticipate the Great Recession--as MMT did--it has put us in the perilous position of blessing the rentiers as the "productive" members of society--exactly the opposite of classical economics!

What is astonishing is how far pundits like Krugman will go to avoid admitting their own mistakes. They're too busy picking the mote out of MMT's eye to deal with the beam in their own.

The Battle Lines Have Been Drawn On The Green New Deal

Naomi Klein

February 13 2019, 6:00 a.m. (in the Intercept)

“I REALLY DON’T like their policies of taking away your car, taking away your airplane flights, of ‘let’s hop a train to California,’ or ‘you’re not allowed to own cows anymore!'”

So bellowed President Donald Trump in El Paso, Texas, his first campaign-style salvo against Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Sen. Ed Markey’s Green New Deal resolution. There will surely be many more.

It’s worth marking the moment. Because those could be the famous last words of a one-term president, having wildly underestimated the public appetite for transformative action on the triple crises of our time: imminent ecological unraveling, gaping economic inequality (including the racial and gender wealth divide), and surging white supremacy.

Or they could be the epitaph for a habitable climate, with Trump’s lies and scare tactics succeeding in trampling this desperately needed framework. That could either help win him re-election, or land us with a timid Democrat in the White House with neither the courage nor the democratic mandate for this kind of deep change. Either scenario means blowing the handful of years left to roll out the transformations required to keep temperatures below catastrophic levels.

Back in October, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a landmark report informing us that global emissions need to be slashed in half in less than 12 years, a target that simply cannot be met without the world’s largest economy playing a game-changing leadership role. If there is a new administration ready to leap into that role in January 2021, meeting those targets would still be extraordinarily difficult, but it would be technically possible — especially if large cities and states like California and New York escalate their ambitions right now. Losing another four years to a Republican or a corporate Democrat, and starting in 2026 is, quite simply, a joke.

So either Trump is right and the Green New Deal is a losing political issue, one he can smear out of existence. Or he is wrong and a candidate who makes the Green New Deal the centerpiece of their platform will take the Democratic primary and then kick Trump’s ass in the general, with a clear democratic mandate to introduce wartime-levels of investment to battle our triple crises from day one. That would very likely inspire the rest of the world to finally follow suit on bold climate policy, giving us all a fighting chance.

Those are the stark options before us. And which outcome we end up with depends on the actions taken by social movements in the next two years. Because these are not questions that will be settled through elections alone. At their core, they are about building political power — enough to change the calculus of what is possible.

That was the lesson of the original New Deal, one we would be wise to remember right now.

The New Deal was a process as much as a project, one that was constantly changing and expanding in response to social pressure from both the right and the left.

Ocasio-Cortez chose to model the Green New Deal after President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s historic raft of programs understanding full well that a central task is to make sure that this mobilization does not repeat the ways in which its namesake excluded and further marginalized many vulnerable groups. For instance, New Deal-era programs and protections left out agricultural and domestic workers (many of them black), Mexican immigrants (some 1 million of whom faced deportation in the 1930s), and Indigenous people (who won some gains but whose land rights were also violated by both massive infrastructure projects and some conservation efforts).

Indeed, the resolution calls for these and other violations to be actively redressed, listing as one of its core goals “stopping current, preventing future, and repairing historic oppression of indigenous peoples, communities of color, migrant communities, deindustrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth.”

I have written before about why the old New Deal, despite its failings, remains a useful touchstone for the kind of sweeping climate mobilization that is our only hope of lowering emissions in time. In large part, this is because there are so few historical precedents we can look to (other than top-down military mobilizations) that show how every sector of life, from forestry to education to the arts to housing to electrification, can be transformed under the umbrella of a single, society-wide mission.

Which is why it is so critical to remember that none of it would have happened without massive pressure from social movements. FDR rolled out the New Deal in the midst of a historic wave of labor unrest: There was the Teamsters’ rebellion and Minneapolis general strike in 1934, the 83-day shutdown of the West Coast by longshore workers that same year, and the Flint sit-down autoworkers strikes in 1936 and 1937. During this same period, mass movements, responding to the suffering of the Great Depression, demanded sweeping social programs, such as Social Security and unemployment insurance, while socialists argued that abandoned factories should be handed over to their workers and turned into cooperatives. Upton Sinclair, the muckraking author of “The Jungle,” ran for governor of California in 1934 on a platform arguing that the key to ending poverty was full state funding of workers’ cooperatives. He received nearly 900,000 votes, but having been viciously attacked by the right and undercut by the Democratic establishment, he fell just short of winning the governor’s office.

All of this is a reminder that the New Deal was adopted by Roosevelt at a time of such progressive and left militancy that its programs — which seem radical by today’s standards — appeared at the time to be the only way to hold back a full-scale revolution.

It’s also a reminder that the New Deal was a process as much as a project, one that was constantly changing and expanding in response to social pressure from both the right and the left. For example, a program like the Civilian Conservation Corps started with 200,000 workers, but when it proved popular eventually expanded to 2 million. That’s why the fact that there are weaknesses in Ocasio-Cortez and Markey’s resolution — and there are a few — is far less compelling than the fact that it gets so much exactly right. There is plenty of time to improve and correct a Green New Deal once it starts rolling out (it needs to be more explicit about keeping carbon in the ground, for instance, and about nuclear and coal never being “clean”). But we have only one chance to get this thing charged up and moving forward.

THE MORE SOBERING lesson is that the kind of mass power that delivered the victories of the New Deal era is far beyond anything possessed by current progressive movements, even if they all combined efforts. That’s why it is so urgent to use the Green New Deal framework as a potent tool to build that power — a vision to both unite movements and dramatically expand them.

Part of that involves turning what is being derided as a left-wing “laundry list” or “wish list” into an irresistible story of the future, connecting the dots between the many parts of daily life that stand to be transformed — from health care to employment, day care to jail cell, clean air to leisure time.

Right now, the Green New Deal reads like a list because House resolutions have to be formatted as lists — lettered and numbered sequences of “whereases” and “resolveds.” It’s also being characterized as an unrelated grab bag because most of us have been trained to avoid a systemic and historical analysis of capitalism and to divide pretty much every crisis our system produces — from economic inequality to violence against women to white supremacy to unending wars to ecological unraveling — in walled-off silos. From within that rigid mindset, it’s easy to dismiss a sweeping and intersectional vision like the Green New Deal as a green-tinted “laundry list” of everything the left has ever wanted.

Now that the resolution is out there, however, the onus is on all of us who support it to help make the case for how our overlapping crises are indeed inextricably linked — and can only be overcome with a holistic vision for social and economic transformation. This is already beginning to happen. For example, Rhiana Gunn-Wright, who is heading up policy for a new think tank largely focused on the Green New Deal, recently pointed out that just as thousands of people moved for jobs during the World War II-era economic mobilization, we should expect a great many to move again to be part of a renewables revolution. And when they do, “unlinking employment from health care means people can move for better jobs, to escape the worst effects of climate, AND re-enter the labor mkt without losing” (her whole Twitter thread is worth reading).

A woman stands on her property on October 5, 2017, about two weeks after Hurricane Maria, in San Isidro, Puerto Rico. Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images

Investing big in public health care is also critical in light of the fact that no matter how fast we move to lower emissions, it is going to get hotter and storms are going to get fiercer. When those storms bash up against health care systems and electricity grids that have been starved by decades of austerity, thousands pay the price with their lives, as they so tragically did in post-Maria Puerto Rico.

And there are many more connections to be drawn. Those complainingabout climate policy being weighed down by supposedly unrelated demands for access to health care and education would do well to remember that the caring professions — most of them dominated by women — are relatively low carbon and can be made even more so. In other words, they deserve to be seen as “green jobs,” with the same protections, the same investments, and the same living wages as male-dominated workforces in the renewables, efficiency, and public-transit sectors. Meanwhile, as Gunn-Wright points out, to make those sectors less male-dominated, family leave and pay equity are a must, which is part of the reason both are included in the resolution.

Drawing out these connections in ways that capture the public imagination will take a massive exercise in participatory democracy. A first step is for every sector touched by the Green New Deal — hospitals, schools, universities, and more — to make their own plans for how to rapidly decarbonize while furthering the Green New Deal’s mission to eliminate poverty, create good jobs, and close the racial and gender wealth divides.

My favorite example of what this could look like comes from the Canadian Union of Postal Workers, which has developed a bold plan to turn every post office in Canada into a hub for a just green transition. Think solar panels on the roof, charging stations out front, a fleet of domestically manufactured electric vehicles from which union members don’t just deliver mail, but also local produce and medicine, and check in on seniors — all supported by the proceeds of postal banking.

TO MAKE THE case for a Green New Deal — which explicitly calls for this kind of democratic, decentralized leadership — every sector in the United States should be developing similar visionary plans for their workplaces right now. And if that doesn’t motivate their members to rush the polls come 2020, I don’t know what will.

We have been trained to see our issues in silos; they never belonged there. In fact, the impact of climate change on every part of our lives is far too expansive and extensive to begin to cover here. But I do need to mention a few more glaring links that many are missing.

A job guarantee, far from an opportunistic socialist addendum, is a critical part of achieving a rapid and just transition. It would immediately lower the intense pressure on workers to take the kinds of jobs that destabilize our planet because all would be free to take the time needed to retrain and find work in one of the many sectors that will be dramatically expanding.

This in turn will reduce the power of bad actors like the Laborers’ International Union of North America who are determined to split the labor movement and sabotage the prospects for this historic effort. Right out of the gate, LIUNA came out swinging against the Green New Deal. Never mind that it contains stronger protections for trade unions and the right to organize than anything we have seen out of Washington in three decades, including the right of workers in high-carbon sectors to democratically participate in their transition and to have jobs in clean sectors at the same salary and benefits levels as before.

A job guarantee, far from an opportunistic socialist addendum, is a critical part of achieving a rapid and just transition.

There is absolutely no rational reason for a union representing construction workers to oppose what would be the biggest infrastructure project in a century, unless LIUNA actually is what it appears to be: a fossil fuel astroturf group disguised as a trade union, or at best a company union. These are the same labor leaders, let us recall, who sided with the tanks and attack dogs at Standing Rock; who fought relentlessly for the construction of the planet-destabilizing Keystone XL pipeline; and who (along with several other building trade union heads) aligned themselves with Trump on his first day in office, smiling for a White House photo op and declaring his inauguration “a great moment for working men and women.”

LIUNA’s leaders have loudly demanded unquestioning “solidarity” from the rest of the trade union movement. But again and again, they have offered nothing but the narrowest self-interest in return, indifferent to the suffering of immigrant workers whose lives are being torn apart under Trump and to the Indigenous workers who saw their homeland turned into a war zone. The time has come for the rest of the labor movement to confront and isolate them before they can do more damage. That could take the form of LIUNA members, confident that the Green New Deal will not leave them behind, voting out their pro-boss leaders. Or it could end with LIUNA being tossed out of the AFL-CIO for planetary malpractice.

The more unionized sectors like teaching, nursing, and manufacturing make the Green New Deal their own by showing how it can transform their workplaces for the better, and the more all union leaders embrace the growth in membership they would see under the Green New Deal, the stronger they will be for this unavoidable confrontation.

ONE LAST CONNECTION I will mention has to do with the concept of “repair.” The resolution calls for creating well-paying jobs “restoring and protecting threatened, endangered, and fragile ecosystems,” as well as “cleaning up existing hazardous waste and abandoned sites, ensuring economic development and sustainability on those sites.”

This is a potential lifeline that we all have a sacred and moral responsibly to reach for.

There are many such sites across the United States, entire landscapes that have been left to waste after they were no longer useful to frackers, miners, and drillers. It’s a lot like how this culture treats people. It’s what has been done to so many workers in the neoliberal period, using them up and then abandoning them to addiction and despair. It’s what the entire carceral state is about: locking up huge sectors of the population who are more economically useful as prison laborers and numbers on the spreadsheet of a private prison than they are as free workers. And the old New Deal did it too, by choosing to exclude and discard so many black and brown and women workers.

There is a grand story to be told here about the duty to repair — to repair our relationship with the earth and with one another, to heal the deep wounds dating back to the founding of the country. Because while it is true that climate change is a crisis produced by an excess of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, it is also, in a more profound sense, a crisis produced by an extractive mindset — a way of viewing both the natural world and the majority of its inhabitants as resources to use up and then discard. I call it the “gig and dig” economy and firmly believe that we will not emerge from this crisis without a shift in worldview, a transformation from “gig and dig” to an ethos of care and repair.

If these kinds of deeper connections between fractured people and a fast-warming planet seem far beyond the scope of policymakers, it’s worth thinking back to the absolutely central role of artists during the New Deal era. Playwrights, photographers, muralists, and novelists were all part of a renaissance of both realist and utopian art. Some held up a mirror to the wrenching misery that the New Deal sought to alleviate. Others opened up spaces for Depression-ravaged people to imagine a world beyond that misery. Both helped get the job done in ways that are impossible to quantify.

In a similar vein, there is much to learn from Indigenous-led movements in Bolivia and Ecuador that have placed at the center of their calls for ecological transformation the concept of buen vivir, a focus on the right to a good life as opposed to more and more and more life of endless consumption, an ethos that is so ably embodied by the current resident of the White House.

The Green New Deal will need to be subject to constant vigilance and pressure from experts who understand exactly what it will take to lower our emissions as rapidly as science demands, and from social movements that have decades of experience bearing the brunt of false climate solutions, whether nuclear power, the chimera of carbon capture and storage, or carbon offsets.

But in remaining vigilant, we also have to be careful not to bury the overarching message: that this is a potential lifeline that we all have a sacred and moral responsibly to reach for.

The young organizers in the Sunrise Movement, who have done so much to galvanize the Green New Deal momentum, talk about our collective moment as one filled with both “promise and peril.” That is exactly right. And everything that happens from here on in should hold one in each hand.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Chinese Humor

In 🇨🇳Nanchang, Jiangxi, sanitation workers dress as Ming dynasty imperial guards as they patrol the streets! They keep the city clean wh...

-

Here's a detailed explanation by a Modern Monetary Theory founder, Stephanie Kelton. The bottom line: Social Security's enabling l...

-

Posted on March 26, 2019 by L. Randall Wray The attacks on MMT continue full steam ahead. Janet Yellen (former Fed chair, but clueless on...

-

© by Mark Dempsey In the year 2000 the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked countries’ health care system outcomes according to thin...