A new report by the carbon emission think-tank The Shift P roject out this week highlights that not much has changed since. ICT still contributes to about 4 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, which is still twice that of civil aviation. What is worse, its contribution is growing more quickly than that of civil aviation.

Glaringly, they note:

At the current pace of digital GHG emissions, the total over the same period of the additional digital emissions in comparison to 2018 will be about 2.1 GtCO2eq, which would cancel about 20% of the necessary effort made to reduce them.

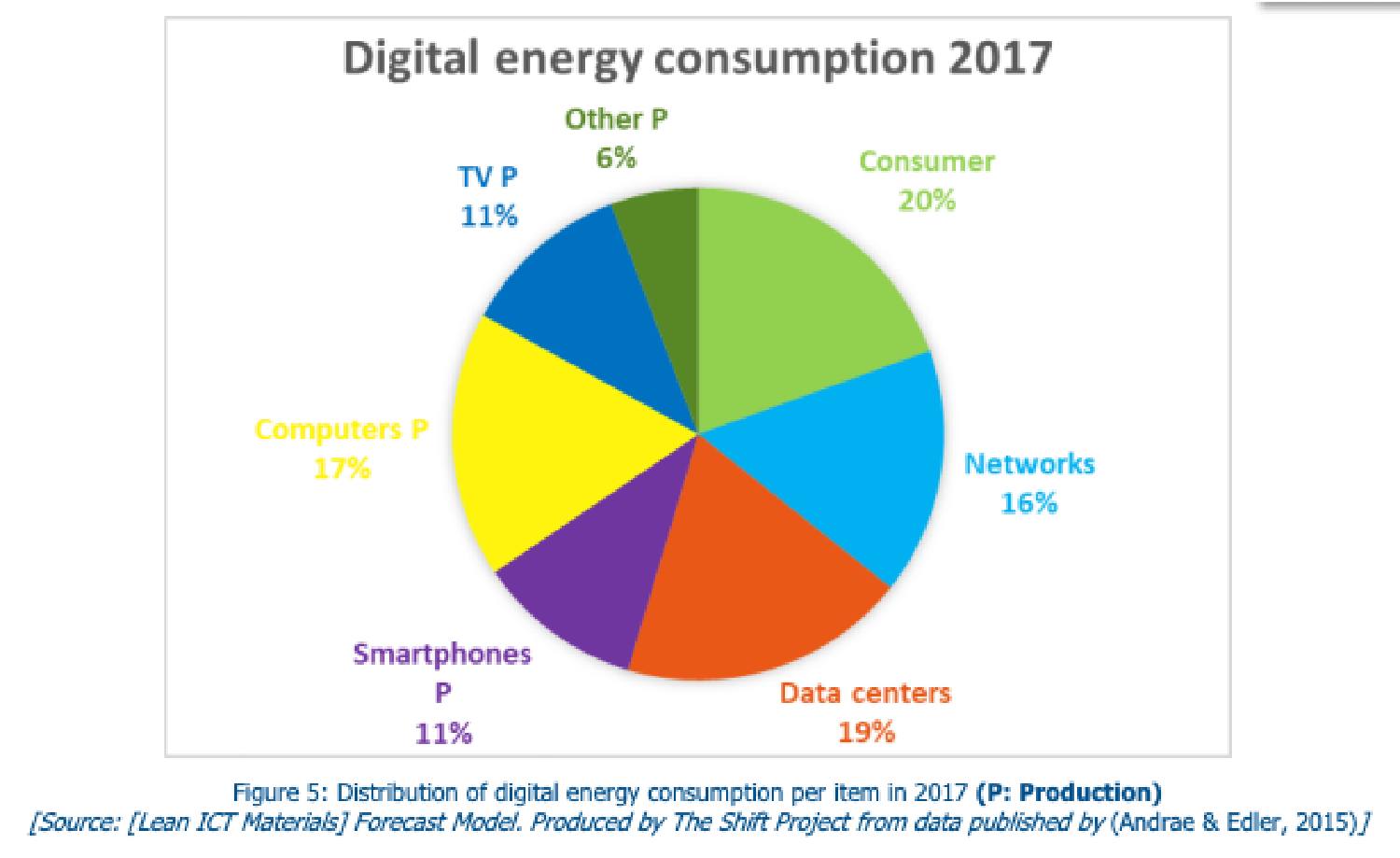

Much of the carbon intensity associated with the ICT sector isn’t even from consumer use (although data centres are bad) but rather from the production of digital devices. Here’s how the report breaks it down:

The bad news is the rise of the internet of things and connected living is only likely to make things worse.

Some interesting points from the report that caught our eye:

- Recharging frequency of our smartphones remains more or less constant despite the fact battery power has increased by 50 per cent in five years (a sign of Jevons paradox in play).

- Obsolescence issues are a key driver of production excess, as successive versions of operating systems are compatible with older generation of terminals only at the cost of degraded performance, or a significant reduction in the useful capacity of the battery.

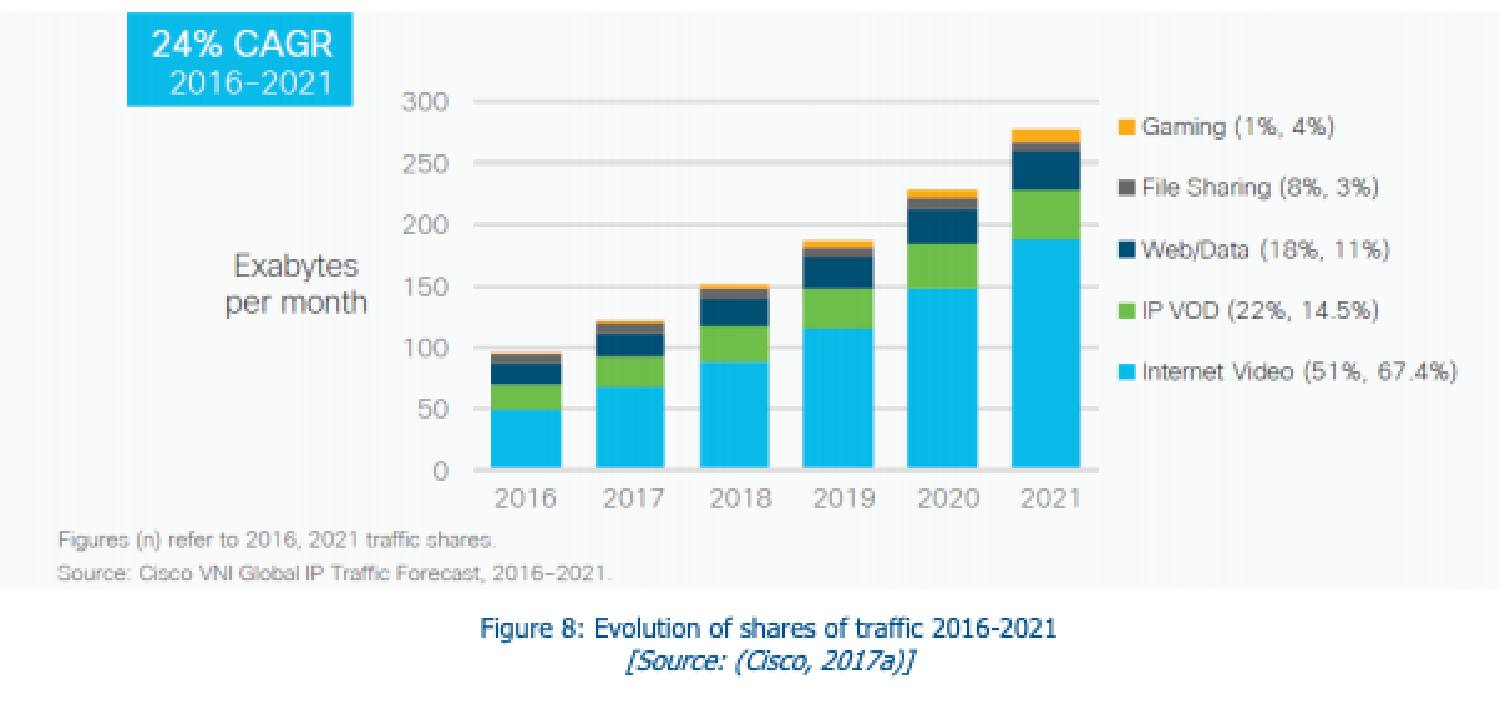

- The explosion of data traffic — especially video traffic from on demand streaming and cloud gaming — is occurring at a rate that surpasses energy efficiency gains in equipment, networks and data centres. These traffic forecasts are also regularly revised upwards:

- Most of the growth in the data flows is attributable to the consumption of services provided by Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Chinese counterparts like Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, Xiaomi. In some cases it can represent 80 per cent of the traffic carried on the networks of certain operators.

- The traffic growth is so strong it raises the question as to the capacity available to ensure sufficient industrial production in terms of storage equipment by 2020.

The writers of the report worry that the uncontrolled growth rate of digital technology may lead to a loss of control or the aggravation of existing environmental imbalances. They add that “the current trend for digital overconsumption in the world is not sustainable with respect to the supply of energy and materials it requires”.

Another critical point is that the energy intensity of the digital industry in the world is only increasing (4 per cent per year), contrary to conventional industrial growth, which is becoming less energy intensive by 1.8 per cent a year.

They sum up the dynamic as follows:

". . . consuming one euro of digital technology in 2018 induces direct and indirect energy consumption 37% higher than what it was in 2010.This trend is the exact opposite of what is generally attributed to digital technology and runs counter to the objectives of energy and climatic decoupling set by the Paris Agreement."

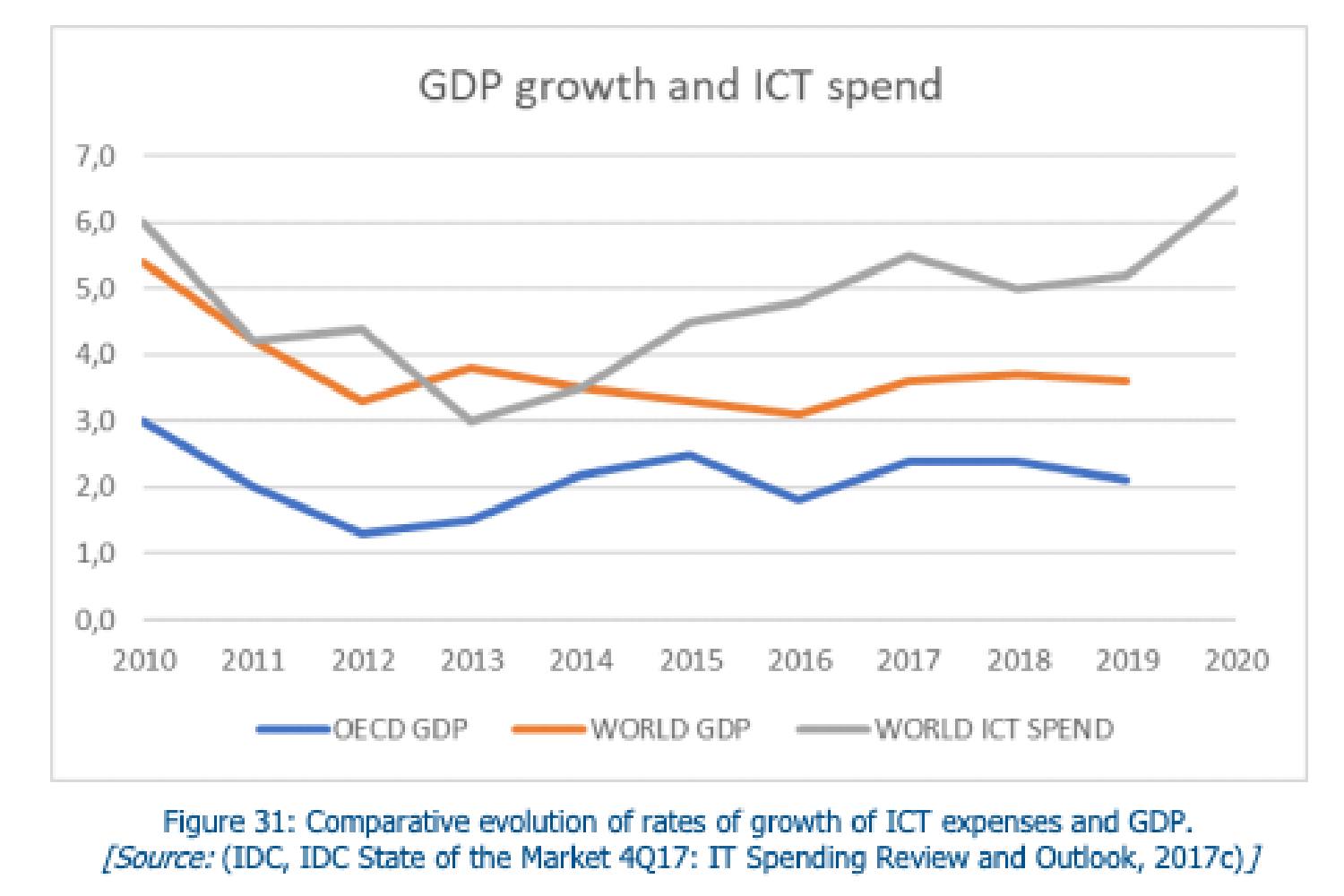

But perhaps the most glaring statistic inadvertently revealed — in support of Robert Gordon's and Robert Solow's innovation theories — is the degree to which increasing digital expense is not contributing to global growth:

Observation of the evolution of world GDP compared to that of digital expenses shows a significant difference in growth in favour of digital technologies. It has risen from 1.5 per cent in 2013 to 3 per cent since 2016 in the OECD zone, which coincides with the deployment of digital transition in these countries. However, whereas the growth of digital technologies has speeded up, the rate of economic growth has stagnated.

So what can be done? The authors advocate a meaningful move towards digital sobriety.

Notably, “returning to the individual and collective capacity to question the social and economic usefulness of our behaviours linked to purchasing and consuming digital objects and services, and to adapting them accordingly in order to avoid immoderation”.

Practically that means: limiting the renewal of terminals, purchasing the least powerful devices possible (be proud of your Nokia 3310!), changing phones as rarely as possible, avoiding multiplication of digital copies and segmenting our video uses to essential actions. Oh, and not mining cryptocurrencies, which weren't mentioned in the report. However, on a call earlier, Maxime Efoui-Hess, one of the authors, said it's an area they are keeping an eye on.

Mr Efoui-Hess told FT Alphaville that it's essentially about prioritising the sort of things you want to do, not just because you can do them.

But will the Fyre Festival “influencer” economy ever go for that? A selfie in time, after all, guarantees many more endorsement kickbacks....

No comments:

Post a Comment

One of the objects if this blog is to elevate civil discourse. Please do your part by presenting arguments rather than attacks or unfounded accusations.