Posted in nakedcapitalism.com on March 30, 2020 by Yves Smith

Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. Another meaty chat with Michael Hudson, who focuses here on the role of finance in rent extraction.

An important theme here that Hudson has stressed before is the mistaken perception of home “ownership”. Only about 1/3 of homes in America are owned free and clear. For the rest, the banks, or mortgage trusts, hold a senior position as mortgage lenders. And over the decades, they have become far less accommodating when homeowners are late even on a single payment. Even worse, insiders have reported that mortgage servicers will even hold payments to assure that they are late, which typically leads to compounding charges that virtually assure a foreclosure. Borrowers also face Kafkaesque obstacles to clearing up errors when they unquestionably paid on time.

To put it another way, as Josh Rosner put it in the early 2000s. “A home with no equity is a rental with debt.” That can be generalized to homes with little equity.

Radical Imagination host Jim Vrettos interviews Professor Michael Hudson, Economist, Wall St. Analyst, Political Consultant, Commentator and Journalist; who offers his views in the way finance works

Welcome, welcome once again to the Radical imagination. I’m your host, Jim Vrettos. I’m a sociologist who’s talked at John Jay College of Criminal justice and Yeshiva University here in New York. Our guest today, on the Radical Imagination, is one of only eight economists named by the Financial Times who foresaw the credit crisis and ensuing great recession erupting in 2008. It was conventional wisdom at the time to say that no one saw the gravity of the crisis coming, including almost every leading economist and financier in the world.

In fact, many had seen it coming. It was seen by everyone except economists from Wall Street; as our guest put it. They were ignored by an establishment according to then, the Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan that watched with innocent quote-unquote shock disbelief as its whole intellectual edifice collapsed in the summer of 2007.

Official models missed the crisis not because the conditions were so shockingly unusual, they missed it by design because the world they lived in was not a world of how finance really works. They missed it because their mathematical models made it impossible to warn against a debt-deflation recession.

Their innocent model worlds were worlds where debt simply did not exist. It’s a world that most of our economic policymakers still live in, and it’s no wonder that everyday people see most economists far removed from their practical economic concerns and interests their everyday concrete reality. Our guest today is an internationally renowned economist who’s followed a much different path of interest and concern.

Michael Hudson is a distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, a researcher at the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College, a former Wall Street analyst; political consultant to governments on finance and tax policy, a popular commentator sought after speaker and journalist.

He identifies himself as a Marxist economist. But his interpretation of Karl Marx that differs in most other major Marxists. He believes parasitical forms of finance have warped the political economy of modern capitalism. History has regressed back to a neo- feudal system. He’s also a contributor to the Hudson report, a weekly economic and financial news podcast produced by Left Out.

His many books include Killing the Host, J is for Junk Economics,The Bubble and Beyond, Super Imperialism, and “… and Forgive Them Their Debts.” Michael has devoted his entire scientific career to the study of debt —both domestic and foreign, loans and mortgages, and interest payments.

In 2006 he argued that debt deflation would shrink the real economy, drive down real wages and push our debt-ridden economy into a Japan-style stagnation or worse. And just for reference, the typical American household now carries an average debt of over $137,000 up from $50,000 or so in 2000. The average American has about $38,000 in personal debt, excluding home mortgages.

The average credit card debt per U.S. household is $8,500, and outstanding student loans are at an all-time high, in 2019, of $1.41 trillion, a 33 percent spike since 2014, and a 6 percent increase from 2018. Only 23 percent of the population say they carry no debt. As Hudson presciently puts it, debts grow and grow, and the more they grow, the more they shrink the economy.

When you shrink the economy, you shrink the ability to pay the debts. So, it’s an illusion that the system can be saved. The question is, how long are people going to be willing to live in this illusion? Every day people have to face reality. Our economic policymakers urgently need to get it too.

So welcome Michael to The Radical Imagination. Thank you very, very much for coming here and being with us. Your work is so interesting; it’s so new and different. You’re a Marxist economist and yet…

[Michael] I’m a classical economist…

[Jim] You are classical, ok.

[Michael] Marx was the last great classical economist. Classical economics basically runs from the French Physiocrats through Adam Smith via John Stuart Mill to Marx.

[Jim] Along with Ricardo.

[Michael] Yes, they were all talking about the rentiers. In their time the landed aristocracy were the main rent recipients. But Adam Smith also talked about monopoly rent. And finance was the major monopoly. And today, the role of the landlords played in the 19th century of stifling industrial capitalism is being played by the banks and the rest of the financial sector. Right now the collectors of land rent, which was the main focus of the labor theory of value to isolate what was unnecessary, is being paid to the banks as mortgage interest.

[Jim] Right

[Michael] So, we no longer have a small privileged private landlord class when you have 80 percent of the European population and two thirds of the American population being homeowners. However, they have to pay the equivalent of the rental value of their housing to the bank, in the form of mortgage interest.

[Jim] To the banks, right!

[Michael] My analysis follows from classical economics, as did Marx’s analysis. So Marx is simply the last great classical economist. They were all talking about how industrial capitalism sought to free itself from unnecessary costs of production, and hence how its political fight was against the landlord class and other rent extractors. Where Marx went beyond his predecessors was in looking at the laws of motion of industrial capitalism. He saw these as leading toward socialism. Later, Rosa Luxemburg said that if it’s not towards socialism, it will be toward barbarism.

[Jim] So capitalism would evolve into the possibility of socialism.

[Michael] Yes.

[Jim] Did he foresee the sort of predatory financial system that you worked out?

[Michael] No one described it better in his time than Marx, in Volume III of Capital.

[Jim] Volume III. Ok!

[Michael] Marx analyzed the “real” economy’s circular flow between employers and wage labor buying the products they produced. But then, in Volume III, he said that rentier debt claims by the financial sector was a separate dynamic, independent from the economy of production and consumption. This industrial capitalist economy is wrapped in a financial sector composed of debt and property claims. These are external to the economy. They slow it and ultimately cause a crash. Marx was one of the first to talk about business cycles of about 11 years and the internal contradictions that led to a market collapse. He pointed out that the financial sector had different mathematics of growth – the mathematics of compound interest. These are exponential and inherently unsustainable. In Volume III of Capital and also of his Theories of Surplus Value– which was Marx’s history of economic thought and the theories leading up to him – he collected everything from Martin Luther to other analyses pointing out that debts grew so rapidly at compound interest that it is impossible to pay them.

[Jim] You have a great chart where you talk about compound interest, a penny that was invested at 5% interest from Christ’s time to 1776.

[Michael] Richard Price was an actuarial accountant. He calculated that a penny saved that at the time of Jesus’s birth at 5% interest would become a solid sphere of gold extending from the sun out to the planet of Jupiter.

[Jim] Amazing.

[Michael] Obviously, many people did save pennies at the time of Christ, and the annual interest rate then in Rome was 8 1/3%, one twelfth per year. But of course nobody has a sphere of gold extending out to Jupiter. That’s because debts that can’t be paid, won’t be.

That’s basically my motto: Debts, that can’t be paid, won’t be paid, because there’s no way of paying out of current income that grows much more slowly, tapering off.

[Jim] Right!

[Michael] So debts have to be written down. It usually takes the form of a financial crash. Nobody before Marx explained crashes in terms of the financial claims growing and causing a break in the chain of payments. The actual break could be a result of fraud or embezzlement, or a bad crop, because crashes happened in the autumn when the crops were moved and there was a drain of money from the banks to pay for moving the crop and paying the harvesters. But at least a crash wiped out debts, and then the debt buildup could begin all over again.

[Jim] But in pre-industrial civilizations that didn’t occur did it? We want to play a short little clip from your book, “… and Forgive Them Their Debts,” in which you talk about the debt phenomenon in primitive or pre-industrial civilizations, very different than what we’ve experiencing today, correct?

[Michael] That’s right. You mentioned the Financial Times report of the economists who did see the crash coming. I was the only one who actually made a chart showing why the break had to come. The Financial Time review was by Dirk Bezemer, who showed the chart that I published in a Harper’s magazine, based on an earlier paper I’d given at the University of Missouri at Kansas City for one of our Minsky Conferences.

[Jim] Let’s play this. It’s a two-minute clip on what you talking about, and debt within pre-industrial societies.

[Clip]

[Michael] Economists don’t talk much about religion or society, or how these concerns shape markets. Theologians for their part act as if religion is all about heaven and sex, so debt is left out. Yet it used to be at the core of Judaism, Christianity, and earlier Near Eastern religion.

[Host] Why is that? If religious leaders are interested in social justice, as Jesus was, it you have to talk about economics.

[Michael] I think part of the reason is that when they translated the Bible into English, German and the vernacular, they didn’t know what many of the words originally meant, like deror (for the Jubilee Year), or how to distinguish between “sin” and “debt” as originally a reparations payment for sin. They didn’t understand that most of the Bible was redacted by the returnees from the Babylonian captivity, who brought back this concept of debt cancellation, “andurarum” – Clean Slate. The Hebrew word was “deror.” In the Bible, you’ll have other words or terms for the Clean Slate, the Jubilee year of Leviticus 25, such as “Year of the Lord” in Jesus’s first sermon.

They didn’t realize that the word “gospel” was the “good news.” That good news was that there was going to be a debt cancellation. They didn’t realize that the Ten Commandments were very largely about debt; that “one shall not covet the neighbor’s wife,” that means you don’t make a loan to the guy so he has to pledge his wife as a debt slave to her so that you can have your way with her.

[Jim] But ordinarily that just gets translated as adultery.

[Michael] Yes, but they didn’t realize that the vehicle for this immorality was largely debt bondage. “Thou shalt not take the Lord’s name in vain” meant that a creditor couldn’t swear that so-and-so owes you money if he didn’t. All of this had to do with fact that the great destabilizing factor in society in the first millennium BC was debt beyond the ability to be paid, leading to bondage of the debtor, and ultimately forfeiture of land to wealthy creditors eager to grab it and do as Isaiah accused, join plot to plot and house to house until there were no more people left in the land.

[Jim] “No more people left in the land.” This is an incredible narrative. Please flesh out the narrative so that we can understand what was going on at that time.

[Michael] In order to explain the dynamics of debt in early times, you have to explain how the overall economic system worked as part of the social system. Most people ran into debt not by borrowing, but simply by not being able to pay the taxes or other payment obligations that accrued. These debts weren’t the result of loans. Most personal debts in Sumer and Babylonia were owed to the palace, so when the crops failed or there was a military fighting they couldn’t pay what they owed to the bureaucracy of tax collectors or for public services.

[Jim] Who were working for the palace.

[Michael] Yes. The rulers had a choice at this point: Either they could let the debtor fall into bondage when he couldn’t pay the tax collectors or the palace. If that happened, he’d owe the crop surplus to the creditor, not the palace.

He owed his payment in labor. That was the scarce resource in antiquity. He’d owe his labor to the creditor, so he couldn’t serve in the army, or do corvee work to build infrastructure or palace walls.

So rulers canceled these personal debts to regain control over agrarian labor and its crop surplus. Every new ruler who took the throne in Sumer and Babylonia started the reign with an amnesty, a Clean Slate to start from a position of balance in Year One. During their subsequent reign, if the crops failed or if there was a military conflict, the ruler would cancel consumer debts (but not commercial debts among businessmen for foreign trade or similar enterprise). That’s in the laws of Hammurabi, cancelled Babylonian debts four times. It’s obvious that if you’re at war or if the crops are hurt, cultivators can’t pay the loans.

What early modern scholars could not believe, until our Harvard group began to compile the economic history of antiquity, that canceling such debts actually was what maintained stability. We began our Harvard group in the 1990’s , and we’ve published five colloquia volumes of the origins of economic enterprise in the ancient Near East, on land tenure, urbanization, debt, and debt cancellation.

Our researches showed that as soon as you had interest-bearing debts (mainly in the commercial sphere), you had debt cancellation for the personal agrarian debts. Business debts were not canceled because the merchants were also citizens, so no matter what, all citizens had their designated self-support land. So only the barley debts were canceled; not the personal debts. We showed that rulers canceled the debts because number one, they were canceling debts owed to themselves. It’s politically easy to forgive a debt if it’s owed to you. But it’s more difficult if there is an oligarchy and debts are owed to private creditors.

Canceling crop debts was what maintained economic stability without mass bankruptcy, which would have meant that a lot of debtors would have ended up as bond servants to their creditors. It also maintained demographic staility, because otherwise, debtors would have run away and joined another community. Many did run away after Babylonia fell in 1600 BC. Four centuries later we find them joining the hapiru, which many people connected to the Hebrews. They were sort of gangs of laborers who also would do a little bit of piracy or serve as mercenaries. Their own groups were very egalitarian, just as pirates were egalitarian in their own ranks in the 18th century West.

With the hapiru you find for the first time an ideology saying that they were not going to let themselves fall into debt to the rich or to landlords. Their ranks were joined by fugitives walking out. Of course, that’s how Rome came to be settled under its “kings,” and what the Roman commoners did 594 BC after the kings were overthrown. The oligarchy took over, and tried to reduce the Roman population to bondage. You had numerous Secessions of the Plebs, for instance, again when the oligarchy broke its word by 449 BC.

[Jim] the aim was to forgive all the debts, just as in the Bible, right?

[Michael] When the Bible really was edited and put together by the Jews who were coming back from Babylonia, they brought back with them many Babylonian practices.

[Jim] So, they had learned from that experience . . .

[Michael] At that time all the Near Eastern kingdoms, even the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires had rulers who continued to proclaim Clean Slates.

[Jim] The Persians and so on. But that tradition didn’t survive into modern times, although it became a tradition within the old Judaism.

[Michael] And also the original preachings of Jesus. Leviticus 25 projected the practice all the way back to the commandments of Moses. But there’s not very much documentation of Judaism after the compilation of the Jewish Bible, because the Judeans didn’t write on clay tablets, they wrote on perishable materials that haven’t survived. The little that did survive was the sacred library of Jerusalem, which became the Dead Sea Scrolls. When the Romans came, they took the library and they put it in pots. We now have many of these scrolls. One was a midrash, a collection of all of the biblical passages about debt cancellation, including those of the prophets.

[Jim] Interesting!

[Michael] So we know that by the time of Jesus, there was an active popular demand for another Jubilee. But meanwhile, within Judaism itself, the wealthiest families became the rabbinical school. Luke’s description of Jesus in the New Testament said that the Pharisees loved money. They became the rabbinical school of Hillel. Luke said that Jesus went back to the temple in his hometown to give a sermon, and unrolled the scroll of Isaiah to read the passage about the Year of the Lord – meaning the Jubilee Year – and said, that he had come to proclaim this year. That was his destiny.

Early translators of the Bible just read “the Year of the Lord” without realizing that this meant the Jubilee Year, deror, a debt cancellation. Luke immediately says a lot of families got very angry and chased Jesus out of town. They didn’t like his message. The Pharisees in particular got upset, and complained to the Roman that Jesus wanted to be King. Well, the reason they said was that they knew that Rome hated kingship. Roman tradition as written by Livy and by Dionysius and Halicarnassus described Servius as cancelling the debts, and most other kings of trying to keep the oligarchy in its place. Rome grew by making itself a haven for immigrants, whom they attracted precisely by keeping the oligarchy in its place.

[Jim] But they also had an empire. . .

[Michael] We are talking before the eighth to sixth centuries BC. But then the oligarchs took over and throughout the rest of Roman history down to the empire, the great fear was that somebody would do what the kings did: cancel the debts and redistribute the land to the poor. Julius Caesar was killed for “seeking kingship,” meaning that the Senate worried that he was going to cancel the debts after decades of civil warfare over this issue and the assassination of Catiline and other advocates of debt cancellation.

[Jim] And people will be free from their economic bondage

[Michael] Yes. Even many rich people were behind Catiline, who led the revolt a generation before Caesar, who actually seems to have been an early sponsor of Catiline. We’re talking about 62 to 64 BC; Caesar was killed in 44 BC.

So to make a long story short, what made the West “Western” was that it was the first society not to cancel the debts. It was to prevent this that oligarchies opposed a central authority. We don’t find any sign of debt in Greece and Rome until about 750 B.C. It was brought by near Eastern traders, along with standardized calendrically based weights and measures, ritual and religious practices. They set up temples as trading vehicles. For thousands of years, traders had set up local temples to act as a sort of Chamber of Commerce, to negotiate trade. In Greece, and Rome at that time there were chieftainships, which began to adopt the patronage practices of extending loans to the population, and then taking the payment and labor.

These dependency relationships are what made Western civilization different from what went before. There was no palatial economy, no state authority to override the oligarchy, cancel debts, redistribute land or liberate citizens who had been reduced to bondage as a result of their debt.

[Jim] You’re talking about the Middle Ages as well, feudalism?

[Michael] No, I’m talking about Greece and Rome in contrast to the Near Eastern mixed economies that were palatial as well as private. There was much private mercantile enterprise in Sumer. Its foreign trade was largely left to private enterprise (with the palace being a major customer, to be sure), so, these were mixed economies, as the five volumes that our Harvard group published have shown.

[Jim] This is all contained in your book “… and Forgive Their Debts.”

[Michael] Yes.

[Jim] So this is what is crucial to understanding lending, foreclosure and redemption from the Bronze Age finance to the Jubilee.

[Michael] Yes.

[Jim] This is a fascinating history. Can we bring it up to date, including issues of militarization and empire and imperialism in the 20thcentury, World Wars I and II? What are some of the things that occurred, the inception of the World Bank and the IMF? How did America control and attempt to defend its empire by using debt leverage?

[Michael] Already in Greece and Rome there was a linkage between debt and militarization. A Greek general, Tacticus in the third century BC, wrote a book of military tactics. He said that if you want to conquer a town, the way to take it over is to promise to cancel the debts. The population will come over to your side. And conversely, he said, if you’re defending a town, cancel the debts and they’ll support you against the attacker. So that was one of the reasons that debts tended to be canceled by one group or another. It’s what Coriolanus did, and then he went back on his word in Rome. That’s what Zedekiah did in Judea. Well, today it’s different. Here you have the imposition of a military force – really NATO – to enforce debt collection, not only from individuals but on debt entire countries. The job of the World Bank and IMF is to impose such heavy debt service on countries, and indeed to impose it in dollars, that countries have to earn these dollars to pay their debts. They can’t simply print the money to pay these debts like America can do. They have to obtain dollars by steadily lowering the price of their labor. But as yet there is no debt revolt.

[Jim] Because, when we went off the gold standard the American dollar became all powerful.

[Michael]Right.

[Jim] And we control 75% of the gold reserves?

[Michael] By the end of World War II, we controlled 75%, right.

[Jim] These are tremendous transformations in the world economy. The IMF and World Bank have supposedly developed through the UN for development, but as you argue, it’s more to create dependency.

[Michael] The World Bank is effectively part of the Defense Department. Their heads are usually former Secretaries of Defense, from John J McCloy, the first president, to McNamara and subsequent heads. What the United States discovered is that you don’t need to go to war to control other countries. If you can have them accept the assumption that all debts should be paid, they will voluntarily submit to austerity, which is class warfare against their own labor force. They will continue to devalue their currency …

[Jim] And create puppet governments that will support that as surrogates.

[Michael] Yes. What the free market boys at the University of Chicago discovered is that you can’t have a pro-financial free market – free of government regulation and its own public infrastructure and credit system – unless you’re prepared to assassinate everyone who wants a strong government. When they went to Chile and supported Pinochet, U.S. officials provided a list of who had to be killed – land reformers, labor leaders, socialists, and especially economics professors. They closed down every Economics Department in the country, except for the one at Catholic University, the right wing economics department teaching Chicago School neoliberalism. So, you have to be totalitarian in order to impose a free market pro-financial style – which, under today’s circumstances, means pro-US.

[Jim] It’s occurring across Latin America, right?

[Michael] Yes. A free market means libertarianism and totalitarian government. What the Chicago boys and the so-called New Institutional Economics school calls the rule of contracts. You have the history of Western civilization now being taught almost everywhere as if what created civilization was the rule of contracts, not canceling the debts. So, you’ve created an inside-out view of history. Its aim is to deny the fact that the only way that you can prevent the kind of economic slowdown that we’re having in America now is to write down the debts. If you don’t write down the debts, you’re internal market will shrink and you’re going to end up looking like Greece, or like France with all the riots that they are having there, or like the other countries that are rioting because they don’t want to be turned into a Neo-feudal society.

[Jim] This seems to be occurring in Puerto Rico as well. So what becomes more profitable for American economy is the military and the armaments that we ship and use in all these adventurers wars that we have in the 800 hundred US military bases around the world.

[Michael] The difference is that in the past when you had militarism, you actually had to fight a war. Soldiers had to go in. You know the old joke about wine that’s being sold in an auction. It’s a hundred-year-old bottle and is very, very expensive. A rich guy buys it and pours it out to impress his friends, but it tastes like vinegar. He complains to the auction house, but is told, “Oh, that’s not wine for drinking! That’s for trading!” That’s what most U.S. arms are for: not really to use. You’re never again going to get Americans to be drafted and go into the army to actually, use them. These arms are not for fighting; they’re for making profits. Seymour Melman explained that in Pentagon Capitalism.

[Jim] The permanent war economy.

[Michael] That’s right. Meaning more profits for the military industrial complex. You don’t actually use the arms. You just pay to produce them and throw them away. It’s like what Keynes talked about, building pyramids in order to create domestic purchasing power.

[Jim] And you can’t, as Melman tried to do, use economic conversion to more civilian uses. That never happened.

[Michael] Seymour Melman explained that the U.S. government decided to make a different kind of a contract with the arms manufacturers. It’s called cost-plus. As he summarized it, the government guarantees them a profit, but to prevent monopoly rents, they determined the prices to be paid at, say, ten percent over the actual cost of production. This led the arms-makers to see that if their profits were going to rise in keeping with the cost of production, they wanted as high of a cost of production as possible.

So, the engineers working on the American military industrial complex aimed at maximizing costs. That’s how we got toilet seats that cost $650.

Countries that don’t have Pentagon capitalism, like Russia or China, are able to produce weaponry that outshines America. Even broke Iran, can make missiles that apparently get right through the U.S. defenses in Syria and Iraq, because they don’t have cost-plus. They’re trying to be efficient, not just to have an excuse for making money via a cost-plus contract.

[Jim] How do we turn this around? You’ve made the connections to show that everyday people and their lives are profoundly impacted by the unreal world that the financial predators are creating.

[Michael] Reality isn’t the aim of their economic models. For instance, just today I saw Paul Krugman on Democracy Now. He said that the reason we’re in a depression is because President Obama did not run a large enough budget deficit! He’s a Keynesian, but goes so far as to insist that debt has no role to play in deflating the economy. That’s largely because Krugman serves in effect as a bank lobbyist – not only here, but in Iceland and other countries. To me, the current economic squeeze is that Obama didn’t let the banks collapse. He kept the bad he debts on the books instead of treating them as bad loans to be absorbed by the banks that wrote the junk mortgages and lost in their speculative gambles.

[Jim] And ate the homeowners!

[Michael] Yes. He kept their bad, outrageously priced loans on the books and evicted 10 million families. He called them “the mob with pitchforks,” and Hillary called them “deplorables.” That shows you where the Democratic Party is at, and why it was so easy for Donald Trump to make a left wing run around the Democratic Party. That is how right wing Obama was. His legacy was Donald Trump, via Hillary Clinton.

[Jim] Krugman is the most well-known so-called Keynesian economist in the country, right?

[Michael] The reason he’s so well-popularized by the pro-financial class is precisely because he doesn’t understand money. So bank lobbyists love him and he’s popularized by the right-wing New York Times. He had a wonderful debate with Steve Keen that anybody can see on Google, where he says that it’s impossible for banks to create money and credit. He thinks that banks are savings banks, and they’re just relending deposits. Steve Keen explained what endogenous money is. That’s what we talk about in Modern Monetary Theory.

[Jim] And the Wall Street Journal.

[Michael] And the Washington Post. They go together. They don’t want economists to be popular who talk about debt and why the debts can’t be paid or the need for a debt write down. Krugman attacks Bernie Sanders as if he is an unbelievable radical for backing public medical care.

[Jim] On February 17, Krugman wrote a column “Have Zombies eaten Bloomberg’s and Buttigieg Brains?” He said “My book is arguing with zombies.” And one of the zombies is his obsession with public debt and the belief that we should be terribly scared of government debt, can’t do anything because of deficits. Eeek! And that’s the way Buttigieg talks. The very moment when mainstream economics, if you like centrist economics, has concluded that these debt worries, were way overblown. The president of American Economic Association gave this presidential address saying that debt is not nearly the problem people think it is. It’s not a constraint, and of course, Republicans have pulled off one of the greatest acts of policy hypocrisy in history – you know, the existential deficit threat. I don’t want to see a democratic centrist bring us into this deficit scaremongering. That would be a really bad thing that would block any kind of initiative.

So, what does the everyday person make of this debate? And what’s the attraction of Trump his message to people who feel that their real-world needs are being addressed?

[Michael] I think the reason people voted for Trump’s was mainly Hillary. She said that voters should vote for the lesser evil. There was no question who the “lesser evil” was. It was Donald Trump. Did you want World War III, or Donald Trump? It’s not a very nice choice, but Hillary’s viciously right-wing, especially where Russia is concerned. The Democratic National Committee and deep state are all about Russia, Russia, Russia! And calling Trump Putin’s puppet.

Then finally the Mueller report came out and found nothing there! So you can view the Democratic Party as the political arm of the military industrial complex and the banking complex.

[Jim] And Obama totally propped them up. But now, Bernie! What about him? The Democratic establishment is against him, and so is the Republican establishment.

[Michael] If the enemy of my enemy is my friend, then Bernie’s enemies are the Democratic Party establishment and the Democratic National Committee. So of course a lot of people are going to love him.

[Jim] Yup. He wants to cancel student debt! He is talking your language!

[Michael] If the student debt is not canceled, you’re going to have a generation of graduates unable to get the mortgage loans to buy homes, because they’re already paying their income to the banks.

[Jim] They’re living at home!

[Michael] That means that you’re going to have a shrinking economy. So of course you have to write down student debt, and also other forms of debt – credit card debt and other debt. The economy cannot recover if you don’t write down the debt overhead.

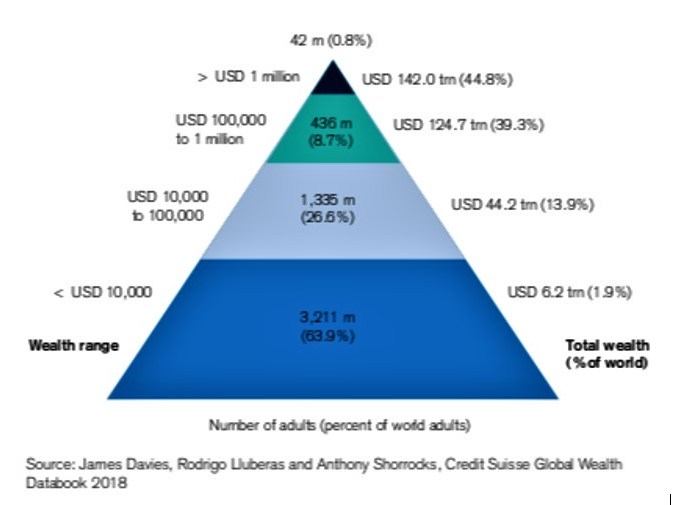

The good thing about writing down the debts is that you wipe out the savings on the other side of the balance sheet. Some 90 percent of the debts in America are owed to the wealthiest 10 Percent. So the problem is not only the debt; it’s all these savings of the One Percent! The world is awash in their wealth. If you don’t wipe out their financial claims – which are the basis of their wealth – they’re going to take you over and become the new financial Lords, just like the feudal landlords. The banks are the equivalent of the Norman invasion. and the conquering landlords that reduce the economy to a peonage!

[Jim] But the moral argument is made that they’re the best. They’ve survived, right? I’m playing devil’s advocate here. So they serve a purpose, don’’ they? Their wealth is a sign that the system is working.

[Michael] That’s not what Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill said, or Ricardo and the entire 19th century classical economic school. They said that economic rent is unearned income. So the aristocracy (“the best”) doesn’t earn it. It is a result of privilege, which almost always is inherited wealth or monopoly privilege, that is, the right to appropriate something that really should be public. Land ownership and mining should be public wealth, as are mineral resources in much of the world. Education should be public. People shouldn’t have to pay for it. The idea initially in the United States was that education should be free as a human right. Medical care is also, as Bernie says, a human right, as it is in a lot of the world. So America, which people used to think was the most progressive capitalist country, suddenly becoming the most neo-feudal economy.

[Jim] How about Max Weber and the Protestant ethic as the spirit of capitalism? The argument is made that those who are productive are rewarded by heaven, while those who are poor deserve it. Wealth was a sign that God had bestowed his grace on its owner.

[Michael] That sort of the patter talk a century ago hasn’t stood up very well. The wealthy claim to be wealthy because God loves them. If they can convince other people that God loves them and hates the rest of the people, they make God into the devil. They make him hate the working class, and make them dependent on this unnecessary class of parasites. That’s crazy! But that’s what happens if you let the wealthy take over religion. Of course, they’re going to say that religion justifies their wealth.

That’s what makes modern religion the opposite of the religion that I described in the Bronze Age. Upon taking the throne, rulers took a pledge to the gods to restore equity and cancel the debts. That included restoring lands that had been forfeited, giving it back to the defaulting debtors to re-establish order. That was the idea of religion back then. But today’s religion has become a handmaiden of wealth and privilege, and of “personal responsibility” to make people pay for education, health care, access to housing and other basic things that should be a public right.

[Jim] Which is what preoccupies the average American, when seventy percent of their earnings are going to these sorts of things, and for taxes and rent. I have a brief quote here from Martin Luther King, who I think represents the sort of religious tradition you’re advocating. He had been deeply influenced by the theologian, Walter Rauschenbusch and his 1907 book, Christianity and the Social Crisis.

[Michael] Read it, so that so they can hear it.

[Jim] Here’s the main quote: “The gospel at its best deals with the whole man; not only his soul, but his body; not only the spiritual well-being, but his material well-being.” King wrote in an inspired passage, “any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the slums that damned them, the economic conditions that strangled them and the social conditions that crippled them is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial.”

[Michael] That’s right. Religion was about the whole economy. Not just a part of the economy. Today they’ve separated religion, as if only spiritual and has nothing to do with the economic organization of society. Religion used to be all about the economic organization of society. So, you’ve had a decontextualization of religion, taking away from analyzing society to justify the status quo by teaching that if things are the way they are, it’s because God wants it this way. That’s saying that God wants the wealthy and privileged to exploit you, especially by getting you into debt. And that’s just crap!

[Jim] And that gets us away from the classical tradition, which does try to see this as social.

[Michael] And that’s why Christian evangelicals hate Jesus so much.

[Jim] There you go! But we love Bernie! Can he win? We’ve only got about a minute to go …

[Michael] Of course he can.

[Jim] You think he will be able to withstand the onslaught that he’s going to get?

[Michael] A year ago I was pretty sure that the Democratic National Committee was going to put the super delegates in to sabotage any attempt that he was going to make to get the nomination. Now it’s clear that the Democratic Party will be torn apart, and this means the end of it if he’s not the nominee.

[Jim] All right! Well, from your mouth to God’s ears! Thank you, Michael. This has been so enlightening.

[Michael] Thank you.

[Jim] I’m so blessed that we are in the audience here too on the Radical Imagination. So happy to have had you here. I hope you’ll come back again. This is your most recent book, “… and Forgive Them Their Debts.” Thank you very much! This is Jim Vrettos for the Radical Imagination. See you next week. Thank you, Michael!

This entry was posted in Banana republic, Credit markets, Economic fundamentals, Guest Post, Income disparity, Politics, Social policy, Student loans, The destruction of the middle class, The dismal science on March 30, 2020 by Yves Smith.

Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. Another meaty chat with Michael Hudson, who focuses here on the role of finance in rent extraction.

An important theme here that Hudson has stressed before is the mistaken perception of home “ownership”. Only about 1/3 of homes in America are owned free and clear. For the rest, the banks, or mortgage trusts, hold a senior position as mortgage lenders. And over the decades, they have become far less accommodating when homeowners are late even on a single payment. Even worse, insiders have reported that mortgage servicers will even hold payments to assure that they are late, which typically leads to compounding charges that virtually assure a foreclosure. Borrowers also face Kafkaesque obstacles to clearing up errors when they unquestionably paid on time.

To put it another way, as Josh Rosner put it in the early 2000s. “A home with no equity is a rental with debt.” That can be generalized to homes with little equity.

Radical Imagination: Imagining How the World of Finance Really Works

Radical Imagination host Jim Vrettos interviews Professor Michael Hudson, Economist, Wall St. Analyst, Political Consultant, Commentator and Journalist; who offers his views in the way finance works

Welcome, welcome once again to the Radical imagination. I’m your host, Jim Vrettos. I’m a sociologist who’s talked at John Jay College of Criminal justice and Yeshiva University here in New York. Our guest today, on the Radical Imagination, is one of only eight economists named by the Financial Times who foresaw the credit crisis and ensuing great recession erupting in 2008. It was conventional wisdom at the time to say that no one saw the gravity of the crisis coming, including almost every leading economist and financier in the world.

In fact, many had seen it coming. It was seen by everyone except economists from Wall Street; as our guest put it. They were ignored by an establishment according to then, the Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan that watched with innocent quote-unquote shock disbelief as its whole intellectual edifice collapsed in the summer of 2007.

Official models missed the crisis not because the conditions were so shockingly unusual, they missed it by design because the world they lived in was not a world of how finance really works. They missed it because their mathematical models made it impossible to warn against a debt-deflation recession.

Their innocent model worlds were worlds where debt simply did not exist. It’s a world that most of our economic policymakers still live in, and it’s no wonder that everyday people see most economists far removed from their practical economic concerns and interests their everyday concrete reality. Our guest today is an internationally renowned economist who’s followed a much different path of interest and concern.

Michael Hudson is a distinguished research professor of economics at the University of Missouri, Kansas City, a researcher at the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College, a former Wall Street analyst; political consultant to governments on finance and tax policy, a popular commentator sought after speaker and journalist.

He identifies himself as a Marxist economist. But his interpretation of Karl Marx that differs in most other major Marxists. He believes parasitical forms of finance have warped the political economy of modern capitalism. History has regressed back to a neo- feudal system. He’s also a contributor to the Hudson report, a weekly economic and financial news podcast produced by Left Out.

His many books include Killing the Host, J is for Junk Economics,The Bubble and Beyond, Super Imperialism, and “… and Forgive Them Their Debts.” Michael has devoted his entire scientific career to the study of debt —both domestic and foreign, loans and mortgages, and interest payments.

In 2006 he argued that debt deflation would shrink the real economy, drive down real wages and push our debt-ridden economy into a Japan-style stagnation or worse. And just for reference, the typical American household now carries an average debt of over $137,000 up from $50,000 or so in 2000. The average American has about $38,000 in personal debt, excluding home mortgages.

The average credit card debt per U.S. household is $8,500, and outstanding student loans are at an all-time high, in 2019, of $1.41 trillion, a 33 percent spike since 2014, and a 6 percent increase from 2018. Only 23 percent of the population say they carry no debt. As Hudson presciently puts it, debts grow and grow, and the more they grow, the more they shrink the economy.

When you shrink the economy, you shrink the ability to pay the debts. So, it’s an illusion that the system can be saved. The question is, how long are people going to be willing to live in this illusion? Every day people have to face reality. Our economic policymakers urgently need to get it too.

So welcome Michael to The Radical Imagination. Thank you very, very much for coming here and being with us. Your work is so interesting; it’s so new and different. You’re a Marxist economist and yet…

[Michael] I’m a classical economist…

[Jim] You are classical, ok.

[Michael] Marx was the last great classical economist. Classical economics basically runs from the French Physiocrats through Adam Smith via John Stuart Mill to Marx.

[Jim] Along with Ricardo.

[Michael] Yes, they were all talking about the rentiers. In their time the landed aristocracy were the main rent recipients. But Adam Smith also talked about monopoly rent. And finance was the major monopoly. And today, the role of the landlords played in the 19th century of stifling industrial capitalism is being played by the banks and the rest of the financial sector. Right now the collectors of land rent, which was the main focus of the labor theory of value to isolate what was unnecessary, is being paid to the banks as mortgage interest.

[Jim] Right

[Michael] So, we no longer have a small privileged private landlord class when you have 80 percent of the European population and two thirds of the American population being homeowners. However, they have to pay the equivalent of the rental value of their housing to the bank, in the form of mortgage interest.

[Jim] To the banks, right!

[Michael] My analysis follows from classical economics, as did Marx’s analysis. So Marx is simply the last great classical economist. They were all talking about how industrial capitalism sought to free itself from unnecessary costs of production, and hence how its political fight was against the landlord class and other rent extractors. Where Marx went beyond his predecessors was in looking at the laws of motion of industrial capitalism. He saw these as leading toward socialism. Later, Rosa Luxemburg said that if it’s not towards socialism, it will be toward barbarism.

[Jim] So capitalism would evolve into the possibility of socialism.

[Michael] Yes.

[Jim] Did he foresee the sort of predatory financial system that you worked out?

[Michael] No one described it better in his time than Marx, in Volume III of Capital.

[Jim] Volume III. Ok!

[Michael] Marx analyzed the “real” economy’s circular flow between employers and wage labor buying the products they produced. But then, in Volume III, he said that rentier debt claims by the financial sector was a separate dynamic, independent from the economy of production and consumption. This industrial capitalist economy is wrapped in a financial sector composed of debt and property claims. These are external to the economy. They slow it and ultimately cause a crash. Marx was one of the first to talk about business cycles of about 11 years and the internal contradictions that led to a market collapse. He pointed out that the financial sector had different mathematics of growth – the mathematics of compound interest. These are exponential and inherently unsustainable. In Volume III of Capital and also of his Theories of Surplus Value– which was Marx’s history of economic thought and the theories leading up to him – he collected everything from Martin Luther to other analyses pointing out that debts grew so rapidly at compound interest that it is impossible to pay them.

[Jim] You have a great chart where you talk about compound interest, a penny that was invested at 5% interest from Christ’s time to 1776.

[Michael] Richard Price was an actuarial accountant. He calculated that a penny saved that at the time of Jesus’s birth at 5% interest would become a solid sphere of gold extending from the sun out to the planet of Jupiter.

[Jim] Amazing.

[Michael] Obviously, many people did save pennies at the time of Christ, and the annual interest rate then in Rome was 8 1/3%, one twelfth per year. But of course nobody has a sphere of gold extending out to Jupiter. That’s because debts that can’t be paid, won’t be.

That’s basically my motto: Debts, that can’t be paid, won’t be paid, because there’s no way of paying out of current income that grows much more slowly, tapering off.

[Jim] Right!

[Michael] So debts have to be written down. It usually takes the form of a financial crash. Nobody before Marx explained crashes in terms of the financial claims growing and causing a break in the chain of payments. The actual break could be a result of fraud or embezzlement, or a bad crop, because crashes happened in the autumn when the crops were moved and there was a drain of money from the banks to pay for moving the crop and paying the harvesters. But at least a crash wiped out debts, and then the debt buildup could begin all over again.

[Jim] But in pre-industrial civilizations that didn’t occur did it? We want to play a short little clip from your book, “… and Forgive Them Their Debts,” in which you talk about the debt phenomenon in primitive or pre-industrial civilizations, very different than what we’ve experiencing today, correct?

[Michael] That’s right. You mentioned the Financial Times report of the economists who did see the crash coming. I was the only one who actually made a chart showing why the break had to come. The Financial Time review was by Dirk Bezemer, who showed the chart that I published in a Harper’s magazine, based on an earlier paper I’d given at the University of Missouri at Kansas City for one of our Minsky Conferences.

[Jim] Let’s play this. It’s a two-minute clip on what you talking about, and debt within pre-industrial societies.

[Clip]

[Michael] Economists don’t talk much about religion or society, or how these concerns shape markets. Theologians for their part act as if religion is all about heaven and sex, so debt is left out. Yet it used to be at the core of Judaism, Christianity, and earlier Near Eastern religion.

[Host] Why is that? If religious leaders are interested in social justice, as Jesus was, it you have to talk about economics.

[Michael] I think part of the reason is that when they translated the Bible into English, German and the vernacular, they didn’t know what many of the words originally meant, like deror (for the Jubilee Year), or how to distinguish between “sin” and “debt” as originally a reparations payment for sin. They didn’t understand that most of the Bible was redacted by the returnees from the Babylonian captivity, who brought back this concept of debt cancellation, “andurarum” – Clean Slate. The Hebrew word was “deror.” In the Bible, you’ll have other words or terms for the Clean Slate, the Jubilee year of Leviticus 25, such as “Year of the Lord” in Jesus’s first sermon.

They didn’t realize that the word “gospel” was the “good news.” That good news was that there was going to be a debt cancellation. They didn’t realize that the Ten Commandments were very largely about debt; that “one shall not covet the neighbor’s wife,” that means you don’t make a loan to the guy so he has to pledge his wife as a debt slave to her so that you can have your way with her.

[Jim] But ordinarily that just gets translated as adultery.

[Michael] Yes, but they didn’t realize that the vehicle for this immorality was largely debt bondage. “Thou shalt not take the Lord’s name in vain” meant that a creditor couldn’t swear that so-and-so owes you money if he didn’t. All of this had to do with fact that the great destabilizing factor in society in the first millennium BC was debt beyond the ability to be paid, leading to bondage of the debtor, and ultimately forfeiture of land to wealthy creditors eager to grab it and do as Isaiah accused, join plot to plot and house to house until there were no more people left in the land.

[Jim] “No more people left in the land.” This is an incredible narrative. Please flesh out the narrative so that we can understand what was going on at that time.

[Michael] In order to explain the dynamics of debt in early times, you have to explain how the overall economic system worked as part of the social system. Most people ran into debt not by borrowing, but simply by not being able to pay the taxes or other payment obligations that accrued. These debts weren’t the result of loans. Most personal debts in Sumer and Babylonia were owed to the palace, so when the crops failed or there was a military fighting they couldn’t pay what they owed to the bureaucracy of tax collectors or for public services.

[Jim] Who were working for the palace.

[Michael] Yes. The rulers had a choice at this point: Either they could let the debtor fall into bondage when he couldn’t pay the tax collectors or the palace. If that happened, he’d owe the crop surplus to the creditor, not the palace.

He owed his payment in labor. That was the scarce resource in antiquity. He’d owe his labor to the creditor, so he couldn’t serve in the army, or do corvee work to build infrastructure or palace walls.

So rulers canceled these personal debts to regain control over agrarian labor and its crop surplus. Every new ruler who took the throne in Sumer and Babylonia started the reign with an amnesty, a Clean Slate to start from a position of balance in Year One. During their subsequent reign, if the crops failed or if there was a military conflict, the ruler would cancel consumer debts (but not commercial debts among businessmen for foreign trade or similar enterprise). That’s in the laws of Hammurabi, cancelled Babylonian debts four times. It’s obvious that if you’re at war or if the crops are hurt, cultivators can’t pay the loans.

What early modern scholars could not believe, until our Harvard group began to compile the economic history of antiquity, that canceling such debts actually was what maintained stability. We began our Harvard group in the 1990’s , and we’ve published five colloquia volumes of the origins of economic enterprise in the ancient Near East, on land tenure, urbanization, debt, and debt cancellation.

Our researches showed that as soon as you had interest-bearing debts (mainly in the commercial sphere), you had debt cancellation for the personal agrarian debts. Business debts were not canceled because the merchants were also citizens, so no matter what, all citizens had their designated self-support land. So only the barley debts were canceled; not the personal debts. We showed that rulers canceled the debts because number one, they were canceling debts owed to themselves. It’s politically easy to forgive a debt if it’s owed to you. But it’s more difficult if there is an oligarchy and debts are owed to private creditors.

Canceling crop debts was what maintained economic stability without mass bankruptcy, which would have meant that a lot of debtors would have ended up as bond servants to their creditors. It also maintained demographic staility, because otherwise, debtors would have run away and joined another community. Many did run away after Babylonia fell in 1600 BC. Four centuries later we find them joining the hapiru, which many people connected to the Hebrews. They were sort of gangs of laborers who also would do a little bit of piracy or serve as mercenaries. Their own groups were very egalitarian, just as pirates were egalitarian in their own ranks in the 18th century West.

With the hapiru you find for the first time an ideology saying that they were not going to let themselves fall into debt to the rich or to landlords. Their ranks were joined by fugitives walking out. Of course, that’s how Rome came to be settled under its “kings,” and what the Roman commoners did 594 BC after the kings were overthrown. The oligarchy took over, and tried to reduce the Roman population to bondage. You had numerous Secessions of the Plebs, for instance, again when the oligarchy broke its word by 449 BC.

[Jim] the aim was to forgive all the debts, just as in the Bible, right?

[Michael] When the Bible really was edited and put together by the Jews who were coming back from Babylonia, they brought back with them many Babylonian practices.

[Jim] So, they had learned from that experience . . .

[Michael] At that time all the Near Eastern kingdoms, even the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires had rulers who continued to proclaim Clean Slates.

[Jim] The Persians and so on. But that tradition didn’t survive into modern times, although it became a tradition within the old Judaism.

[Michael] And also the original preachings of Jesus. Leviticus 25 projected the practice all the way back to the commandments of Moses. But there’s not very much documentation of Judaism after the compilation of the Jewish Bible, because the Judeans didn’t write on clay tablets, they wrote on perishable materials that haven’t survived. The little that did survive was the sacred library of Jerusalem, which became the Dead Sea Scrolls. When the Romans came, they took the library and they put it in pots. We now have many of these scrolls. One was a midrash, a collection of all of the biblical passages about debt cancellation, including those of the prophets.

[Jim] Interesting!

[Michael] So we know that by the time of Jesus, there was an active popular demand for another Jubilee. But meanwhile, within Judaism itself, the wealthiest families became the rabbinical school. Luke’s description of Jesus in the New Testament said that the Pharisees loved money. They became the rabbinical school of Hillel. Luke said that Jesus went back to the temple in his hometown to give a sermon, and unrolled the scroll of Isaiah to read the passage about the Year of the Lord – meaning the Jubilee Year – and said, that he had come to proclaim this year. That was his destiny.

Early translators of the Bible just read “the Year of the Lord” without realizing that this meant the Jubilee Year, deror, a debt cancellation. Luke immediately says a lot of families got very angry and chased Jesus out of town. They didn’t like his message. The Pharisees in particular got upset, and complained to the Roman that Jesus wanted to be King. Well, the reason they said was that they knew that Rome hated kingship. Roman tradition as written by Livy and by Dionysius and Halicarnassus described Servius as cancelling the debts, and most other kings of trying to keep the oligarchy in its place. Rome grew by making itself a haven for immigrants, whom they attracted precisely by keeping the oligarchy in its place.

[Jim] But they also had an empire. . .

[Michael] We are talking before the eighth to sixth centuries BC. But then the oligarchs took over and throughout the rest of Roman history down to the empire, the great fear was that somebody would do what the kings did: cancel the debts and redistribute the land to the poor. Julius Caesar was killed for “seeking kingship,” meaning that the Senate worried that he was going to cancel the debts after decades of civil warfare over this issue and the assassination of Catiline and other advocates of debt cancellation.

[Jim] And people will be free from their economic bondage

[Michael] Yes. Even many rich people were behind Catiline, who led the revolt a generation before Caesar, who actually seems to have been an early sponsor of Catiline. We’re talking about 62 to 64 BC; Caesar was killed in 44 BC.

So to make a long story short, what made the West “Western” was that it was the first society not to cancel the debts. It was to prevent this that oligarchies opposed a central authority. We don’t find any sign of debt in Greece and Rome until about 750 B.C. It was brought by near Eastern traders, along with standardized calendrically based weights and measures, ritual and religious practices. They set up temples as trading vehicles. For thousands of years, traders had set up local temples to act as a sort of Chamber of Commerce, to negotiate trade. In Greece, and Rome at that time there were chieftainships, which began to adopt the patronage practices of extending loans to the population, and then taking the payment and labor.

These dependency relationships are what made Western civilization different from what went before. There was no palatial economy, no state authority to override the oligarchy, cancel debts, redistribute land or liberate citizens who had been reduced to bondage as a result of their debt.

[Jim] You’re talking about the Middle Ages as well, feudalism?

[Michael] No, I’m talking about Greece and Rome in contrast to the Near Eastern mixed economies that were palatial as well as private. There was much private mercantile enterprise in Sumer. Its foreign trade was largely left to private enterprise (with the palace being a major customer, to be sure), so, these were mixed economies, as the five volumes that our Harvard group published have shown.

[Jim] This is all contained in your book “… and Forgive Their Debts.”

[Michael] Yes.

[Jim] So this is what is crucial to understanding lending, foreclosure and redemption from the Bronze Age finance to the Jubilee.

[Michael] Yes.

[Jim] This is a fascinating history. Can we bring it up to date, including issues of militarization and empire and imperialism in the 20thcentury, World Wars I and II? What are some of the things that occurred, the inception of the World Bank and the IMF? How did America control and attempt to defend its empire by using debt leverage?

[Michael] Already in Greece and Rome there was a linkage between debt and militarization. A Greek general, Tacticus in the third century BC, wrote a book of military tactics. He said that if you want to conquer a town, the way to take it over is to promise to cancel the debts. The population will come over to your side. And conversely, he said, if you’re defending a town, cancel the debts and they’ll support you against the attacker. So that was one of the reasons that debts tended to be canceled by one group or another. It’s what Coriolanus did, and then he went back on his word in Rome. That’s what Zedekiah did in Judea. Well, today it’s different. Here you have the imposition of a military force – really NATO – to enforce debt collection, not only from individuals but on debt entire countries. The job of the World Bank and IMF is to impose such heavy debt service on countries, and indeed to impose it in dollars, that countries have to earn these dollars to pay their debts. They can’t simply print the money to pay these debts like America can do. They have to obtain dollars by steadily lowering the price of their labor. But as yet there is no debt revolt.

[Jim] Because, when we went off the gold standard the American dollar became all powerful.

[Michael]Right.

[Jim] And we control 75% of the gold reserves?

[Michael] By the end of World War II, we controlled 75%, right.

[Jim] These are tremendous transformations in the world economy. The IMF and World Bank have supposedly developed through the UN for development, but as you argue, it’s more to create dependency.

[Michael] The World Bank is effectively part of the Defense Department. Their heads are usually former Secretaries of Defense, from John J McCloy, the first president, to McNamara and subsequent heads. What the United States discovered is that you don’t need to go to war to control other countries. If you can have them accept the assumption that all debts should be paid, they will voluntarily submit to austerity, which is class warfare against their own labor force. They will continue to devalue their currency …

[Jim] And create puppet governments that will support that as surrogates.

[Michael] Yes. What the free market boys at the University of Chicago discovered is that you can’t have a pro-financial free market – free of government regulation and its own public infrastructure and credit system – unless you’re prepared to assassinate everyone who wants a strong government. When they went to Chile and supported Pinochet, U.S. officials provided a list of who had to be killed – land reformers, labor leaders, socialists, and especially economics professors. They closed down every Economics Department in the country, except for the one at Catholic University, the right wing economics department teaching Chicago School neoliberalism. So, you have to be totalitarian in order to impose a free market pro-financial style – which, under today’s circumstances, means pro-US.

[Jim] It’s occurring across Latin America, right?

[Michael] Yes. A free market means libertarianism and totalitarian government. What the Chicago boys and the so-called New Institutional Economics school calls the rule of contracts. You have the history of Western civilization now being taught almost everywhere as if what created civilization was the rule of contracts, not canceling the debts. So, you’ve created an inside-out view of history. Its aim is to deny the fact that the only way that you can prevent the kind of economic slowdown that we’re having in America now is to write down the debts. If you don’t write down the debts, you’re internal market will shrink and you’re going to end up looking like Greece, or like France with all the riots that they are having there, or like the other countries that are rioting because they don’t want to be turned into a Neo-feudal society.

[Jim] This seems to be occurring in Puerto Rico as well. So what becomes more profitable for American economy is the military and the armaments that we ship and use in all these adventurers wars that we have in the 800 hundred US military bases around the world.

[Michael] The difference is that in the past when you had militarism, you actually had to fight a war. Soldiers had to go in. You know the old joke about wine that’s being sold in an auction. It’s a hundred-year-old bottle and is very, very expensive. A rich guy buys it and pours it out to impress his friends, but it tastes like vinegar. He complains to the auction house, but is told, “Oh, that’s not wine for drinking! That’s for trading!” That’s what most U.S. arms are for: not really to use. You’re never again going to get Americans to be drafted and go into the army to actually, use them. These arms are not for fighting; they’re for making profits. Seymour Melman explained that in Pentagon Capitalism.

[Jim] The permanent war economy.

[Michael] That’s right. Meaning more profits for the military industrial complex. You don’t actually use the arms. You just pay to produce them and throw them away. It’s like what Keynes talked about, building pyramids in order to create domestic purchasing power.

[Jim] And you can’t, as Melman tried to do, use economic conversion to more civilian uses. That never happened.

[Michael] Seymour Melman explained that the U.S. government decided to make a different kind of a contract with the arms manufacturers. It’s called cost-plus. As he summarized it, the government guarantees them a profit, but to prevent monopoly rents, they determined the prices to be paid at, say, ten percent over the actual cost of production. This led the arms-makers to see that if their profits were going to rise in keeping with the cost of production, they wanted as high of a cost of production as possible.

So, the engineers working on the American military industrial complex aimed at maximizing costs. That’s how we got toilet seats that cost $650.

Countries that don’t have Pentagon capitalism, like Russia or China, are able to produce weaponry that outshines America. Even broke Iran, can make missiles that apparently get right through the U.S. defenses in Syria and Iraq, because they don’t have cost-plus. They’re trying to be efficient, not just to have an excuse for making money via a cost-plus contract.

[Jim] How do we turn this around? You’ve made the connections to show that everyday people and their lives are profoundly impacted by the unreal world that the financial predators are creating.

[Michael] Reality isn’t the aim of their economic models. For instance, just today I saw Paul Krugman on Democracy Now. He said that the reason we’re in a depression is because President Obama did not run a large enough budget deficit! He’s a Keynesian, but goes so far as to insist that debt has no role to play in deflating the economy. That’s largely because Krugman serves in effect as a bank lobbyist – not only here, but in Iceland and other countries. To me, the current economic squeeze is that Obama didn’t let the banks collapse. He kept the bad he debts on the books instead of treating them as bad loans to be absorbed by the banks that wrote the junk mortgages and lost in their speculative gambles.

[Jim] And ate the homeowners!

[Michael] Yes. He kept their bad, outrageously priced loans on the books and evicted 10 million families. He called them “the mob with pitchforks,” and Hillary called them “deplorables.” That shows you where the Democratic Party is at, and why it was so easy for Donald Trump to make a left wing run around the Democratic Party. That is how right wing Obama was. His legacy was Donald Trump, via Hillary Clinton.

[Jim] Krugman is the most well-known so-called Keynesian economist in the country, right?

[Michael] The reason he’s so well-popularized by the pro-financial class is precisely because he doesn’t understand money. So bank lobbyists love him and he’s popularized by the right-wing New York Times. He had a wonderful debate with Steve Keen that anybody can see on Google, where he says that it’s impossible for banks to create money and credit. He thinks that banks are savings banks, and they’re just relending deposits. Steve Keen explained what endogenous money is. That’s what we talk about in Modern Monetary Theory.

[Jim] And the Wall Street Journal.

[Michael] And the Washington Post. They go together. They don’t want economists to be popular who talk about debt and why the debts can’t be paid or the need for a debt write down. Krugman attacks Bernie Sanders as if he is an unbelievable radical for backing public medical care.

[Jim] On February 17, Krugman wrote a column “Have Zombies eaten Bloomberg’s and Buttigieg Brains?” He said “My book is arguing with zombies.” And one of the zombies is his obsession with public debt and the belief that we should be terribly scared of government debt, can’t do anything because of deficits. Eeek! And that’s the way Buttigieg talks. The very moment when mainstream economics, if you like centrist economics, has concluded that these debt worries, were way overblown. The president of American Economic Association gave this presidential address saying that debt is not nearly the problem people think it is. It’s not a constraint, and of course, Republicans have pulled off one of the greatest acts of policy hypocrisy in history – you know, the existential deficit threat. I don’t want to see a democratic centrist bring us into this deficit scaremongering. That would be a really bad thing that would block any kind of initiative.

So, what does the everyday person make of this debate? And what’s the attraction of Trump his message to people who feel that their real-world needs are being addressed?

[Michael] I think the reason people voted for Trump’s was mainly Hillary. She said that voters should vote for the lesser evil. There was no question who the “lesser evil” was. It was Donald Trump. Did you want World War III, or Donald Trump? It’s not a very nice choice, but Hillary’s viciously right-wing, especially where Russia is concerned. The Democratic National Committee and deep state are all about Russia, Russia, Russia! And calling Trump Putin’s puppet.

Then finally the Mueller report came out and found nothing there! So you can view the Democratic Party as the political arm of the military industrial complex and the banking complex.

[Jim] And Obama totally propped them up. But now, Bernie! What about him? The Democratic establishment is against him, and so is the Republican establishment.

[Michael] If the enemy of my enemy is my friend, then Bernie’s enemies are the Democratic Party establishment and the Democratic National Committee. So of course a lot of people are going to love him.

[Jim] Yup. He wants to cancel student debt! He is talking your language!

[Michael] If the student debt is not canceled, you’re going to have a generation of graduates unable to get the mortgage loans to buy homes, because they’re already paying their income to the banks.

[Jim] They’re living at home!

[Michael] That means that you’re going to have a shrinking economy. So of course you have to write down student debt, and also other forms of debt – credit card debt and other debt. The economy cannot recover if you don’t write down the debt overhead.

The good thing about writing down the debts is that you wipe out the savings on the other side of the balance sheet. Some 90 percent of the debts in America are owed to the wealthiest 10 Percent. So the problem is not only the debt; it’s all these savings of the One Percent! The world is awash in their wealth. If you don’t wipe out their financial claims – which are the basis of their wealth – they’re going to take you over and become the new financial Lords, just like the feudal landlords. The banks are the equivalent of the Norman invasion. and the conquering landlords that reduce the economy to a peonage!

[Jim] But the moral argument is made that they’re the best. They’ve survived, right? I’m playing devil’s advocate here. So they serve a purpose, don’’ they? Their wealth is a sign that the system is working.

[Michael] That’s not what Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill said, or Ricardo and the entire 19th century classical economic school. They said that economic rent is unearned income. So the aristocracy (“the best”) doesn’t earn it. It is a result of privilege, which almost always is inherited wealth or monopoly privilege, that is, the right to appropriate something that really should be public. Land ownership and mining should be public wealth, as are mineral resources in much of the world. Education should be public. People shouldn’t have to pay for it. The idea initially in the United States was that education should be free as a human right. Medical care is also, as Bernie says, a human right, as it is in a lot of the world. So America, which people used to think was the most progressive capitalist country, suddenly becoming the most neo-feudal economy.

[Jim] How about Max Weber and the Protestant ethic as the spirit of capitalism? The argument is made that those who are productive are rewarded by heaven, while those who are poor deserve it. Wealth was a sign that God had bestowed his grace on its owner.

[Michael] That sort of the patter talk a century ago hasn’t stood up very well. The wealthy claim to be wealthy because God loves them. If they can convince other people that God loves them and hates the rest of the people, they make God into the devil. They make him hate the working class, and make them dependent on this unnecessary class of parasites. That’s crazy! But that’s what happens if you let the wealthy take over religion. Of course, they’re going to say that religion justifies their wealth.

That’s what makes modern religion the opposite of the religion that I described in the Bronze Age. Upon taking the throne, rulers took a pledge to the gods to restore equity and cancel the debts. That included restoring lands that had been forfeited, giving it back to the defaulting debtors to re-establish order. That was the idea of religion back then. But today’s religion has become a handmaiden of wealth and privilege, and of “personal responsibility” to make people pay for education, health care, access to housing and other basic things that should be a public right.

[Jim] Which is what preoccupies the average American, when seventy percent of their earnings are going to these sorts of things, and for taxes and rent. I have a brief quote here from Martin Luther King, who I think represents the sort of religious tradition you’re advocating. He had been deeply influenced by the theologian, Walter Rauschenbusch and his 1907 book, Christianity and the Social Crisis.

[Michael] Read it, so that so they can hear it.

[Jim] Here’s the main quote: “The gospel at its best deals with the whole man; not only his soul, but his body; not only the spiritual well-being, but his material well-being.” King wrote in an inspired passage, “any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the slums that damned them, the economic conditions that strangled them and the social conditions that crippled them is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial.”

[Michael] That’s right. Religion was about the whole economy. Not just a part of the economy. Today they’ve separated religion, as if only spiritual and has nothing to do with the economic organization of society. Religion used to be all about the economic organization of society. So, you’ve had a decontextualization of religion, taking away from analyzing society to justify the status quo by teaching that if things are the way they are, it’s because God wants it this way. That’s saying that God wants the wealthy and privileged to exploit you, especially by getting you into debt. And that’s just crap!

[Jim] And that gets us away from the classical tradition, which does try to see this as social.

[Michael] And that’s why Christian evangelicals hate Jesus so much.

[Jim] There you go! But we love Bernie! Can he win? We’ve only got about a minute to go …

[Michael] Of course he can.

[Jim] You think he will be able to withstand the onslaught that he’s going to get?

[Michael] A year ago I was pretty sure that the Democratic National Committee was going to put the super delegates in to sabotage any attempt that he was going to make to get the nomination. Now it’s clear that the Democratic Party will be torn apart, and this means the end of it if he’s not the nominee.

[Jim] All right! Well, from your mouth to God’s ears! Thank you, Michael. This has been so enlightening.

[Michael] Thank you.

[Jim] I’m so blessed that we are in the audience here too on the Radical Imagination. So happy to have had you here. I hope you’ll come back again. This is your most recent book, “… and Forgive Them Their Debts.” Thank you very much! This is Jim Vrettos for the Radical Imagination. See you next week. Thank you, Michael!