By ZEPHYR TEACHOUT

Albany is reeling, but fighting the kind of corruption that plagues not only New York State but the whole nation isn’t just about getting cuffs on the right guy. As with the recent conviction of the former Virginia governor Bob McDonnell for receiving improper gifts and loans, a fixation on plain graft misses the more pernicious poison that has entered our system.

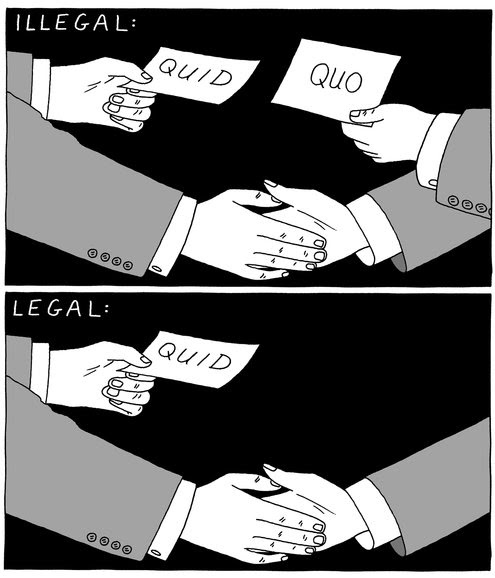

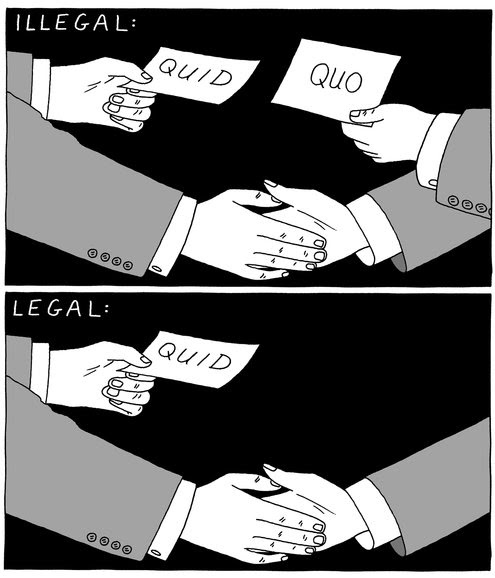

Corruption exists when institutions and officials charged with serving the public serve their own ends. Under current law, campaign contributions are illegal if there is an explicit quid pro quo, and legal if there isn’t. But legal campaign contributions can be as bad as bribes in creating obligations. The corruption that hides in plain sight is the real threat to our democracy.

Think of campaign contributions as the gateway drug to bribes. In our private financing system, candidates are trained to respond to campaign cash and serve donors’ interests. Politicians are expected to spend half their time talking to funders and to keep them happy. Given this context, it’s not hard to see how a bribery charge can feel like a technical argument instead of a moral one.

The former governor of New York David A. Paterson, for example, said that he had trouble understanding where the criminality lay in the allegation that Mr. Silver accepted payments from law firms for referrals, including referrals by a doctor to whom Mr. Silver funneled state health research funds. Mr. Paterson said, “in the legal profession, people refer business all the time. And theoretically, as a speaker, you could do that as well.”

The legal shades into the illegal. The real estate developers represented by the law firm that allegedly shuttled payments to Mr. Silver for fake legal services were also major campaign contributors. One developer mentioned in the charges gave more than $10 million to political campaigns in the past decade, including $200,000 to Mr. Silver and his political action committees.

The structure of private campaign finance has essentially pre-corrupted our politicians, so that they can’t even recognize explicit bribery because it feels the same as what they do every day. When you spend a lifetime serving campaign donors, it may seem easy to serve them when they come with an outright bribe, because it doesn’t seem that different.

Mr. Silver retained such tight control over budgets and lawmaking in Albany that his staffers were regarded as more powerful than most elected representatives. As a Democrat who cares about education, I can’t say that I loved seeing Mr. Silver, a great public school advocate, in handcuffs. For others, there’s glee in seeing the perp walk. But one high-profile indictment does not represent the dawn of a new democracy.

Photo

Credit

Peter Arkle

LAST Thursday, Sheldon Silver,

the speaker of the New York Assembly for the past 20 years, was

arrested and charged with mail and wire fraud, extortion and receiving

bribes. According to Preet Bharara, the federal prosecutor who brought

the charges, the once seemingly untouchable Mr. Silver took millions of

dollars for legal work he did not do. In exchange, he used his official

power to steer business to a law firm that specialized in getting tax

breaks for real estate developers, and he directed state funds to a

doctor who referred cases to another law firm that paid Mr. Silver fees.

Credit

Peter Arkle

LAST Thursday, Sheldon Silver,

the speaker of the New York Assembly for the past 20 years, was

arrested and charged with mail and wire fraud, extortion and receiving

bribes. According to Preet Bharara, the federal prosecutor who brought

the charges, the once seemingly untouchable Mr. Silver took millions of

dollars for legal work he did not do. In exchange, he used his official

power to steer business to a law firm that specialized in getting tax

breaks for real estate developers, and he directed state funds to a

doctor who referred cases to another law firm that paid Mr. Silver fees.

Albany is reeling, but fighting the kind of corruption that plagues not only New York State but the whole nation isn’t just about getting cuffs on the right guy. As with the recent conviction of the former Virginia governor Bob McDonnell for receiving improper gifts and loans, a fixation on plain graft misses the more pernicious poison that has entered our system.

Corruption exists when institutions and officials charged with serving the public serve their own ends. Under current law, campaign contributions are illegal if there is an explicit quid pro quo, and legal if there isn’t. But legal campaign contributions can be as bad as bribes in creating obligations. The corruption that hides in plain sight is the real threat to our democracy.

Think of campaign contributions as the gateway drug to bribes. In our private financing system, candidates are trained to respond to campaign cash and serve donors’ interests. Politicians are expected to spend half their time talking to funders and to keep them happy. Given this context, it’s not hard to see how a bribery charge can feel like a technical argument instead of a moral one.

The former governor of New York David A. Paterson, for example, said that he had trouble understanding where the criminality lay in the allegation that Mr. Silver accepted payments from law firms for referrals, including referrals by a doctor to whom Mr. Silver funneled state health research funds. Mr. Paterson said, “in the legal profession, people refer business all the time. And theoretically, as a speaker, you could do that as well.”

The legal shades into the illegal. The real estate developers represented by the law firm that allegedly shuttled payments to Mr. Silver for fake legal services were also major campaign contributors. One developer mentioned in the charges gave more than $10 million to political campaigns in the past decade, including $200,000 to Mr. Silver and his political action committees.

The structure of private campaign finance has essentially pre-corrupted our politicians, so that they can’t even recognize explicit bribery because it feels the same as what they do every day. When you spend a lifetime serving campaign donors, it may seem easy to serve them when they come with an outright bribe, because it doesn’t seem that different.

Mr. Silver retained such tight control over budgets and lawmaking in Albany that his staffers were regarded as more powerful than most elected representatives. As a Democrat who cares about education, I can’t say that I loved seeing Mr. Silver, a great public school advocate, in handcuffs. For others, there’s glee in seeing the perp walk. But one high-profile indictment does not represent the dawn of a new democracy.

We

should take this moment to pursue fundamental reform. We must

reconstitute what it means to run for office and to serve in office. We

need to ban outside income for elected officials. Transparency alone is

not enough; it doesn’t solve the problem of creating outside

dependencies. New York lawmakers can’t carry water for two masters when

in office.

We should reject the private financing of campaigns as the only model. We need to provide enough public funding for campaigns so that anyone with a broad base of support can run for office, and respond effectively to attacks, without becoming dependent on private patrons. Running for office shouldn’t be a job defined by permanent begging at the feet of the wealthiest donors in the country.

Those two reforms would be transformational. We will never eradicate every shady deal, but we can make politics more about serving the public and less like legalized bribery.

There’s one last thing we should do: ban corporate spending and limit total campaign spending. Last week not only saw Mr. Silver in handcuffs, it also marked the fifth anniversary of the Citizens United ruling, in which the Supreme Court decided that outside corporate spending was in no way corrupting. We will have to revisit that decision, but we don’t need to wait for the court to act.

Corruption is about greed and private interests put ahead of the public good. Whether influence is bought through a bribe, outside spending, outside income or campaign contributions, the public suffers in the same way. Until we move past scandals toward structural change, our democracy will suffer, too.

Zephyr Teachout, an associate professor of law at Fordham, is the author of “Corruption in America: From Benjamin Franklin’s Snuff Box to Citizens United.”

We should reject the private financing of campaigns as the only model. We need to provide enough public funding for campaigns so that anyone with a broad base of support can run for office, and respond effectively to attacks, without becoming dependent on private patrons. Running for office shouldn’t be a job defined by permanent begging at the feet of the wealthiest donors in the country.

Those two reforms would be transformational. We will never eradicate every shady deal, but we can make politics more about serving the public and less like legalized bribery.

There’s one last thing we should do: ban corporate spending and limit total campaign spending. Last week not only saw Mr. Silver in handcuffs, it also marked the fifth anniversary of the Citizens United ruling, in which the Supreme Court decided that outside corporate spending was in no way corrupting. We will have to revisit that decision, but we don’t need to wait for the court to act.

Corruption is about greed and private interests put ahead of the public good. Whether influence is bought through a bribe, outside spending, outside income or campaign contributions, the public suffers in the same way. Until we move past scandals toward structural change, our democracy will suffer, too.

Zephyr Teachout, an associate professor of law at Fordham, is the author of “Corruption in America: From Benjamin Franklin’s Snuff Box to Citizens United.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

One of the objects if this blog is to elevate civil discourse. Please do your part by presenting arguments rather than attacks or unfounded accusations.